California is in the midst of a major shift in terms of how rooftop solar PV, smart inverters, behind-the-meter batteries, smart thermostats and EV chargers, and other distributed energy resources will be valued as part of the grid.

Like many such big policy measures, it’s moving slowly, but tectonically, with subtle behind-the-scenes shifts that could determine the outcome of billions of dollars' worth of investment.

Over the past few months, we’ve seen rumblings of conflict emerge between Pacific Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison and San Diego Gas & Electric on one side, and environmental and clean energy industry groups on the other, over one such policy thread with big implications. It’s part of the California Public Utilities Commission Distribution Resources Plan (DRP) proceeding -- more specifically, the locational net benefits analysis (LNBA) portion.

In recent CPUC filings, groups including the Environmental Defense Fund, Vote Solar, and the Center for Sustainable Energy have been voicing concern over what they say are gaps in the utilities’ proposed LNBA metrics, methods and pilot projects. Central to their complaint is the decision by utilities so far to stick to their tried-and-true method of identifying, valuing and bidding out contracts for distributed energy resources (DERs) to provide locational net benefits -- and remain silent on alternative methods.

The Center for Sustainable Energy (CSE) sets it out pretty clearly in its March CPUC comments:

The investor‐owned utilities have framed the issue of DER locational value in black-and-white terms -- DERs procured through utility competitive solicitations to defer specific investments have locational value, while all other DER growth is viewed as consumer-driven and has no locational value.

What these groups are looking for instead is some form of transparent calculation of the real costs and benefits of DERs of various types across the grid. One term for it is distribution marginal cost, or DMC. Simply put, it's a value at individual nodes of the distribution grid of DERs’ real-time energy generation or load reduction, voltage and frequency support, resiliency, capacity, flexibility and environmental benefits, all in relation to the wires, poles and transformers alternative -- not just in the moment, but for decades to come.

There’s no policy mechanism for bringing a DMC metric like this into use at present, although the sister proceeding to the DRP, called Integrated Distributed Energy Resources (IDER), is taking on that challenge. Utilities have always built and maintained their distribution grids on their own internal cost and benefit measures, based on a guaranteed rate of return on investments deemed fair and accurate enough by state regulators to pass on to ratepayers. They can’t be blamed for taking the tested RFP route, rather than trusting hundreds of millions of dollars of plans to an untested valuation meant to draw DER investment from the private sector.

But the ground rules being established today could have an outsized influence on how DERs end up being valued in California's broader regulatory restructuring, the Environmental Defense Fund wrote in a January filing. “Planning processes that encourage beneficial DERs at the locational level could spill over to the wider utility system, thereby creating expansive value. Likewise, transactive structures could provide flexible, value-based customer-driven opportunities to harvest DER benefits. Conversely, utility planning processes that codify DER investments to direct benefits primarily or solely to the utility could degrade customer choice and crowd out other valuable expenditures.”

Locational net benefits, or the plus side of the DER-to-grid equation

The CPUC launched the DRP in 2014 with the goal of getting PG&E, SCE and SDG&E to shift a portion of their billion-dollar annual distribution grid upgrade investments to DER alternatives. To inform the policy around this cost-shifting concept, the DRP set up two key metrics.

The first is integrated capacity analysis, or ICA, which collects location-specific circuit data to know how much new DER capacity any particular area can handle. The online DER interconnection maps released by the three IOUs last year apply circuit-by-circuit DER capacity ratings using data that’s being built into each one’s ICA framework, for example, and it’s the subject of the first set of pilot projects each utility will be doing as part of the DRP.

The second, LNBA, seeks to establish the positive locational value of a whole range of DER alternatives to traditional grid investments. Rather than being limiting in principle, as the ICA is, it’s expansive. The CPUC’s January scoping memo offered a long list of questions it wanted utilities to answer in their plans, including how to value locational peak reduction capacity, voltage and power quality management capability, and the “common communication and control infrastructure to support ‘smart’ DER.”

But so far, “The utilities have said the only value for distributed energy resources is in deferring transmission and distribution grid upgrades,” Jim Baak, grid integration program director at nonprofit group Vote Solar, said in an interview last week. “Distributed energy resources can provide a lot more services to the grid, like voltage support, frequency support, ramp support, absorbing power,” and other benefits that aren’t clearly defined in utility proposals so far, he said.

Where utilities are consistent with each other in approach, they’re “inconsistent in assumptions applied to the value components, are vague on the actual calculations, and lack examples of how each utility will actually apply the methodologies,” Vote Solar wrote in a January CPUC filing. The appendix of this filing includes a comprehensive breakdown of the three utilities’ LNBA proposals so far. Here’s a chart from GTM Research’s recent report, Unlocking the Value of Distributed Energy Resources 2016: Technology Strategies, Opportunities and Markets, that covers the fundamentals.

Third-party solar provider and behind-the-meter battery player SolarCity has made its own request list. In a January CPUC filing, it asked the commission to incorporate values including deferred capital and operating expenditures related to capacity, distribution voltage, power quality, reliability and resiliency; locational marginal pricing (LMP)-specific avoided energy costs and avoided local resource adequacy procurement. It also wants to add conservation voltage reduction (CVR), the life-extension benefits on equipment from DERs that reduce peak loads, and the potential for mass-market DERs to reduce wholesale energy prices in years to come.

SolarCity and the Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA) also asked the commission to include avoided operational costs in the list of potential benefits to assess. "Examples of avoided operation costs include: 1) streamlining and decreasing interconnection costs by leveraging the monitoring and sensing capabilities of DER assets, 2) mitigating costly grid events by leveraging unique data acquisition and control capabilities of DER assets, and 3) decreasing truck roll-outs by leveraging remote upgrade capabilities of DER assets to change settings as grid conditions require," the groups wrote in a March filing.

For now, however, utilities have made it clear that they want to maintain control over the particulars of how these complex LNBA factors are brought to bear in the real world. That includes identifying where they’re needed, packaging them into particular values and putting them out to bid, much as they've done with the distributed energy resources they’ve gotten to date. Pacific Gas & Electric’s January CPUC filing makes the general point well:

PG&E believes that an overall Locational Net Benefits Methodology (LNBM) should adopt and apply the all-source competitive solicitation principles that have been applied to PG&E’s energy procurement under the Long Term Procurement Plan and Assembly Bill 57 (i.e., Public Utilities Code Section 454.4) for the last decade. PG&E recommends that the Commission apply these commercial principles and protocols to the procurement of DERs for energy, capacity and distribution system deferral under PG&E’s DRP.

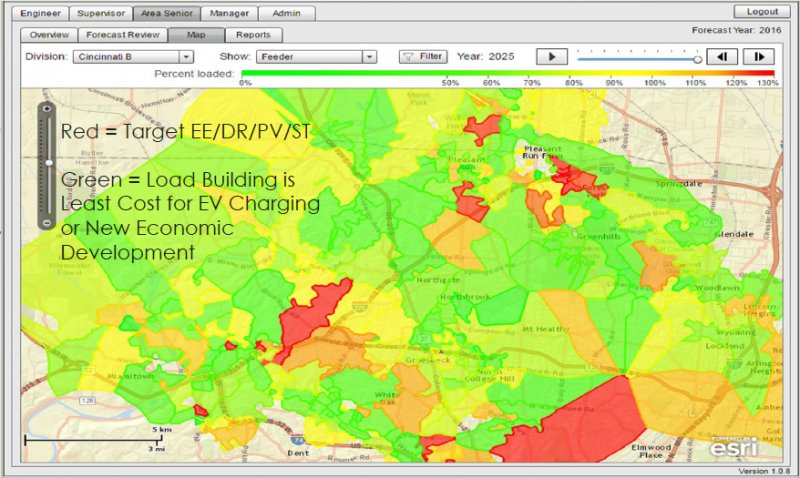

This is pretty much how Southern California Edison procured its groundbreaking 200+ megawatts of DERs back in 2014, featuring contract winners such as Stem, Advanced Microgrid Solution, Ice Energy and NRG Energy. In its January filing, SCE agreed with PG&E that it intends to “use competitive solicitations to acquire DER services,” with “specific information to developers on DER requirements needed to defer a project while remaining technology-agnostic.” While it will offer “indicative heat maps” of deferral value and other information for DER providers, those aren’t specifically linked to the fundamental RFP process.

Looking at options beyond the RFP: Distributed marginal cost

What utilities aren’t interested in right now is setting a price for distributed energy’s locational net benefits. “PG&E does not support administratively determined LNBM pricing under the DRP because such an approach could result in above-market prices and uneconomic costs to PG&E’s customers,” the utility said in its January filing.

This “administratively determined LNBM pricing” is a stand-in for some of the different ideas for bringing distributed marginal cost-type calculations to bear. Vote Solar used the term distribution marginal cost, or DMC, while EDF is calling for “geographically transparent, marginal cost-based prices throughout the utility service territories.”

SolarCity calls it marginal distribution cost, or MDC, and in a February CPUC workshop presentation, it noted that such a metric could enable a broader set of utility-to-DER business relationships than the straightforward RFP. Those could include firm contracts for services, as well as price signals via specialized tariffs like a voluntary rate for distributed marginal pricing (DMP) -- another acronym describing an approach similar to DMC, only expressed in terms of prices, not costs.

Proponents of this approach say it could open up a far broader range of DER applications for analysis by third parties across the board. “The distribution marginal cost structure allows the utility to identify the whole stack of values for distributed energy on the grid, and then you present that on a GIS map, and you let people offer services to you based on that,” Vote Solar’s Baak said.

Finding the true, or at least reasonably accurate, distributed marginal cost or price for thousands of points on the grid and millions of customers is a daunting task, however. As Vote Solar wrote in its January filing, “We recognize that implementing such a solution requires all the IOUs to develop interval data down to the line section or service transformer level, as well as new software tools, both of which may take time to implement.”

California’s utilities have been completing projects that are vital to even getting started on the task, such as upgrades to its geographic information systems and advanced distribution management systems. They’re also experimenting with distributed energy resource management systems, or DERMS -- software to manage distributed energy resources with some level of real-time sensoring and control.

The distributed marginal cost concept takes these real-time operations parameters and expands them to include decades of future time -- the decades in which DERs will either make broader demographic and energy trends worse or better, depending on where they’re placed and at what cost. It’s a close cousin to the distributed marginal price (DMP) calculation done by Cincinnati-based software developer Integral Analytics, which has been working with PG&E and San Diego Gas & Electric on implementing their ICA and LNBA work.

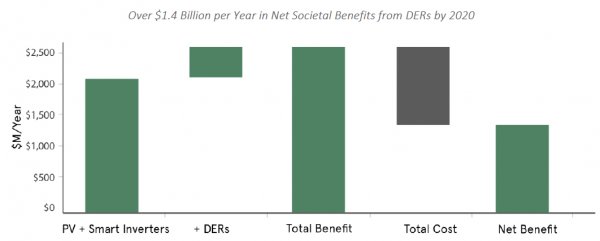

Eric Woychik, an independent consultant who’s worked with Integral Analytics, Comverge and CAISO in the past, told a CPUC workshop in February that applying these formulas could yield DER alternatives that are, on average, two to five times less costly than the traditional grid infrastructure alternative.

Finding the right way to share the benefits of DERs between utilities and third parties

To be fair, not all the capabilities that DERs can deliver are worth that much in certain situations on the grid, GTM Research grid director Ben Kellison noted. “Voltage support may mean little, because there’s a capacitor that was installed two years ago,” he said. “There are factors that people are overestimating, or best case, aren’t considering all the components involved.”

The value of DERs is very location-specific and time-sensitive -- a UC-Berkeley study showed that only 10 percent of PG&E's feeders saw a benefit from rooftop solar as a resource to defer capacity upgrades, with diminishing returns as the first-in solar solved the most expensive problem. That makes for urgency on the part of DER companies to get a piece of utilities’ grid investments before traditional replacements moot the point for years to come.

But there’s an even bigger threat looming in the future for California’s investor-owned utilities. They earn a guaranteed rate of return on the billions of dollars they spend on distribution grid upgrades and improvements every year.

“The utilities only make money if they put assets into operation,” Vote Solar’s Baak said. With an LNBA in place, and a mechanism for DER providers to bid in more cost-effective alternatives, “You’re asking them to avoid a substation upgrade, which can cost tens or hundreds of millions of dollars, and instead, sign a contract for distributed energy resources," he said.

And if DERs end up being twice as cost-efficient as the business-as-usual investment, that could lead to $100 million in capital costs replaced with $50 million in DER replacement. In other words, the utility has just lost $50 million in rate-of-return-guaranteed capital expenditure, based on some calculation of the near- and long-term value of a bunch of assets it doesn't own to make that grid improvement 50 percent more efficient.

This is a deadly calculus for utilities, unless the difference in lost capex and the value created by the lower-cost DER alternative can be corrected for in some way -- and the CPUC is well aware of the problem. At the California’s Distributed Energy Future conference last week in San Francisco, GTM Research’s senior vice president Shayle Kann pointed out this quote from a CPUC scoping memo:

“We anticipate the issuance of a Ruling in the near future…to begin discussion of any necessary changes to the current framework of financial incentives for the investor-owned utilities. The goal of any such changes would be to remove any financial disincentives that the utilities may face in considering the deployment of distributed energy resources in lieu of potential utility capital investments. The future role of the investor-owned utility and/or utility affiliates in the ownership of distributed energy resources may also be addressed.”

Just what models may emerge from this process are still unclear, however. To complicate matters, the CPUC's IDER proceeding, which is moving on a different schedule, may be the proper place to start laying out the pricing and program rules to put the LNBA into effect. "[T]he dividing lines between LNBA methods...to determine optimal locations for [DER] deployment, versus the financial arrangements to pay for grid services (approved in the IDER proceeding) are as yet unclear, and require further exploration," a CPUC staff filing from January points out.

In the meantime, third parties like SolarCity have their own ideas for California DER-grid policy, including SolarCity's concept of a “distribution loading order” for DRP planning, and an “infrastructure-as-a-service” model that could allow utilities to recover shareholder value for investments in third-party DERs.

Other options include adding a higher rate of return to DER investments to allow utilities to make up for the reduced capital expenditures they're making.

Pilot projects as the next decision point

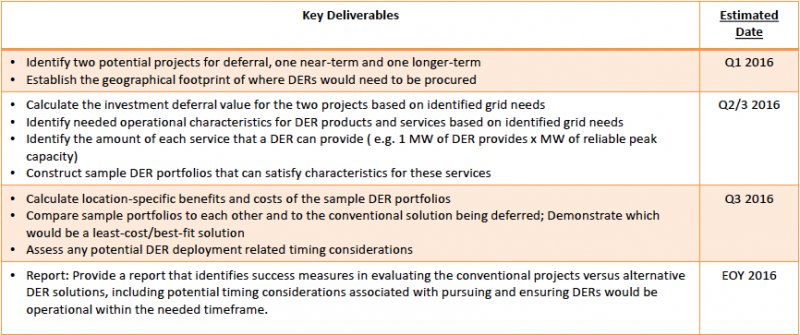

So what happens next? Much of this year’s focus is on the “Demonstration B” pilots called for in the DRP, which are being proposed by utilities to test the LNBA metrics against distribution substation deferral cases. At last week's California’s Distributed Energy Future conference, CPUC Commission Michael Picker declined to discuss how the commission planned to balance the views of utilities and third parties on these subjects. But he did say that interested parties should look to the upcoming pilot project discussion for more insight.

“Most people think the key is what pilots the CPUC approves this year,” Stephanie Wang, senior policy and regulatory attorney for the Center for Sustainable Energy, said in a recent email. CSE is working on alternate DRP pilots, aimed at finding ways to bring LNBA values to non-utility actors in ways outside the traditional RFP process.

Vote Solar has an even more radical suggestion for these pilot projects. "Rather than spending the next 12 months with a continuation of three disparate LNBA approaches, Vote Solar believes that time is better spent establishing a common understanding of the DMC methodology and a path forward for each [investor-owned utility] to establish DMC as the basis for its LNBA," it wrote in a March filing. "We recommend that, after establishing a common understanding of the DMC approach, the Commission require each utility to identify 20 capital projects that are candidates for deferral by DER, and to develop and refine its DMC approach using these 20 projects, including the creation of the LNBA handbooks, over the next six months."