The permitting, siting and financing obstacles to the building of new transmission lines in the face of NIMBY (Not In My Backyard) and BANANA (Build Absolutely Nothing Anywhere Near Anything) activists are familiar. But Aftab Khan, Vice President and General Manager of U.S. Grid Systems for multinational engineering giant ABB, sees a new game afoot.

Khan has watched the old game since starting at ABB 18 years ago. “A lot of what we would do for utility customers or transmission companies was to evaluate what the best solutions were for them,” Khan said, “both AC and DC.”

The late nineteenth-century War of Currents pitted George Westinghouse and alternating current (AC) against Thomas Edison and direct current (DC). Because electricity was then primarily delivered over short distances to consumers from nearby power plants, Westinghouse and AC won.

But DC is the key to the new game. “Power on a DC line is completely controlled. If you say, ‘I want to bring power from point A to point B and I want exactly this many megawatts on that line,” Khan said, “the power goes.” Theoretically, he added, AC lines can do the same. But in an AC system, “you don’t have the ability to manage the power flow from point A to point B directly.”

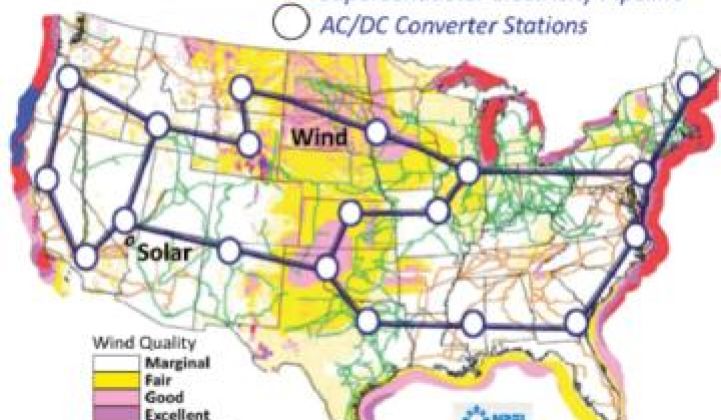

The new game is possible because transmission systems around the world are adding renewables. Vast renewable resources -- be they North Sea and Texas winds or Saharan and Mohave solar -- are being developed far from population centers and transmission systems. “You have a lot of wind capacity in the Midwest and into Texas, and you have a lot of load going out to the West and to the East,” Khan noted. “DC makes perfect sense. Point A to point B, send X number of megawatts that way. It achieves exactly what you need to do.”

Semiconductors and advances in electronics have also paved the way for high-voltage DC transmission.

ABB built the first 200-mile, 100-kilovolt, 20-megawatt DC line in Sweden in the 1950s. There are now, Khan said, more than 145 working or pending HVDC projects worldwide (and HVDC line manufacturer ABB is involved in more than 70 of those projects). Few are located in the U.S. -- so far.

Meanwhile, others such as Valdius DC Power Systems and Nextek Power Systems are devising equipment that convert AC power to DC for use in data centers or buildings. How popular is the concept? Nextek recently hosted delegations from China, Singapore and Japan, said Lian Downey, director of digital applications for the company. With DC coming straight from HDVC lines, efficiency would be increased even more.

"We are living in a DC world. Everything that uses electricity internally users DC power," she said.

China built a 1,200-megawatt capacity DC project in the late 1980s to deliver remote hydroelectric power to burgeoning urban populations. Earlier this year, ABB and Chinese partners “completed and commissioned” an 800-kilovolt, 6,400-megawatt capacity line in China. The country has really pushed the technology, Khan said. “They’re building more and more of these HVDC lines to access more and more of their remote generation resources.” As a result, Chinese transmission developers have joined ABB, Siemens and Alstom Grid as the most important handlers of HVDC transmission.

The cumbersome U.S. transmission development process allows for more stakeholder input, Khan noted, and the thrashing out of issues such as whether new transmission might be a vehicle for more fossil fuel generation (Khan believes it will not). But delays leave remote renewable resources stranded. The new game, Khan thinks, can resolve the conundrum.

“What Texas is doing, they’re investing 5 billion dollars or so in transmission infrastructure that goes out to where the wind potential is,” Khan said. “The logic is that if the wires are there, then a wind developer will say ‘OK, now I can build a wind farm and get it connected and sell the power.’”

But the Texas solution of pre-identifying Competitive Renewable Energy Zones (CREZs) into which new transmission can be built may not work elsewhere. Texas’ own big population centers consume its wind-generated electricity. Midwestern winds need to be delivered across many state and regional regulatory borders. That’s where the new game comes in.

Two-line HVDC transmission systems are less expensive than three-line AC systems and incur fewer instances of line loss to resistance. There is, however, an added expense due to the need for power converter equipment. Over longer distances, however, the benefits outweigh the costs. “It’s such a complex calculation,” Khan said, but “if you’re going over a couple of hundred miles, you should consider DC.”

Another advantage of HVDC lines, significantly simplifying the siting process, is they can be built underground or underwater over distances with little line loss, whereas “with AC lines, you don’t get much out of the other end” if you use these kind of non-traditional sites.

HVDC systems are now being proposed and initiated by entrepreneurial transmission developers such as Clean Light Energy Partners, Transmission Developers, TransWest Express, and a Google-led consortium, Khan said. “They’re wanting to develop long-haul transmission lines,” despite the necessity of “crossing multiple state lines and multiple jurisdictions,” whereas “there isn’t any existing transmission company that would ever want to do that.”

With the market advantages of HVDC, developers “can actually build a business case around it. Because they have complete control of power on that line, they can sign up wind developers on one end” and “they can sign up a utility on the other end to buy the power.”

Players in the new game have -- for now -- won a major blessing from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). “Traditional transmission is cost-based,” Khan explained. FERC is giving the new transmission entrepreneurs “the right to negotiate rates on their line.”

Khan sees the new game as “really exciting, and something they don’t do in China.” Though controversial and not without hurdles, he said, “DC has opened up an opportunity that wouldn’t have existed otherwise.”

***

Michael Kanellos contributed to this article.