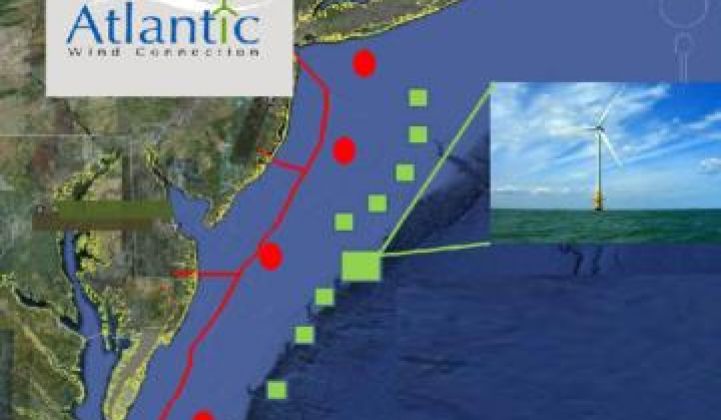

Offshore wind is coming to the Eastern Seaboard and the wires that take its electricity to the grid will earn a lot of money. The Atlantic Wind Connection (AWC) developer wants to build a $1.3 billion, 6-gigawatt capacity high voltage direct current (HVDC) seabed backbone line from New Jersey to Virginia that could serve 1.9 million homes and provide over 200,000 jobs. But companies with vested interests have begun objecting.

A request for rates from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), a normal first step for builders of new transmission, has turned into the first major hurdle for Atlantic Grid Development (AGD), led by independent transmission builder Trans-Elect and sponsored by Good Energies, Google, Inc., and Marubeni Corporation.

Objections have been filed with FERC by the region’s public and private utilities, rural electric cooperatives and offshore wind developers with ties to utilities and power market suppliers. Most have vested interests in existing sources of electricity generation and transmission capabilities that stand to be compromised if the AWC makes vast new sources of wind power available to the onshore grid.

Oceana, the world’s biggest ocean conservation group, filed a statement with FERC in support of the AWC. Supporting filings that the AWC’s incentive rate request be approved came from Fishermen’s Energy and APEX Offshore Wind, developers who are not affiliated with utilities and would therefore benefit from the AWC.

AWC opponents have questioned whether AGD should be filing for those incentive rates, though such rates are provided for in the Energy Policy Act of 2005. AGD will not let such questions slow it down.

“It is appropriate and necessary to grant the AWC Companies’ requested incentives,” AWC argued in its most recent FERC filing, because doing otherwise would “frustrate the extraordinary efforts of the Mid-Atlantic States, the Department of Interior (DOI) and the Department of Energy (DOE) to expedite large-scale offshore wind development.”

“It’s a normal filing,” Markian Melnyk, the AGD President, said. “It’s exactly what Congress intended when they passed that section of the Federal Power Act.” It was intended to encourage transmission projects “that would reduce congestion and improve reliability.” And that, Melnkyk said, “is what we’re proposing.”

Opponents’ filings with FERC, according to the AGD filing, have argued the transmission project would be a disservice to New Jersey ratepayers and “is too speculative to be granted incentives.”

“Some people have said we shouldn’t get any incentives until we have been properly vetted in the PJM transmission planning process,” Melnyk said, referring to the regional transmission organization (RTO) that will ultimately oversee the interconnection of the AWC to the grid. “What they don’t understand is that it’s really a two-step process,” Melnyk explained. “You go to FERC,” he said, “that’s Step A. Step B is you go to PJM.”

Incentives granted by FERC in Step A do not take effect, Melnyk said, until Step B is complete and PJM approves the project as practical and economic.

FERC’s mandate under the Federal Power Act requires it to consider “the benefits of a transmission project” including the need for renewables to meet state mandates. AWC noted in its most recent FERC filing that the “Mid-Atlantic States, DOI and DOE are working fervently to expedite the large-scale development of offshore wind.” There is, the AWC filing pointed out, “a demonstrable need for offshore wind generation to meet RPS standards” because eleven of the fourteen PJM states have renewable requirements and “meeting these state RPS requirements would require up to 25,000 MW of wind by 2015 and 50,000 MW by 2025.”

That the AWC developer is requesting rates that include federal incentives is appropriate, their filing contended, because “the AWC Companies face a multitude of significant regulatory, financial and technical risks in developing the AWC Project.”

Because of those challenges, AGD wants to use the construction work in progress (CWIP) plan, a decades-old cost-allocation construct allowing builders of power system infrastructure to slowly introduce charges to ratepayers who would benefit as they build.

“If you spread out that impact to the rate base over a longer period of time,” Melnyk explained, “you avoid giving consumers rate shock.” Furthermore, Melnyk said, “we would not be charging consumers and making money until an independent entity, PJM, determined that we are the right project.”

No matter what, Melnyk said, “the full cost of transmission has to be recovered from ratepayers.” But, he said, “if we build the backbone system, we will avoid some of that cost” because the AWC constitutes a central and more versatile system than interconnections built by offshore wind developers on a project-by-project basis. The AWC will also bring wind from a wider geographic distribution onto the grid, reducing the impact of wind’s variability.

In both ways, Melnyk said, AWC will facilitate the development of the East Coast’s 54 gigawatts of wind potential, driving the explosion of a full-scale offshore wind manufacturing sector “and the jobs that come with it.”