It's no secret that the cost of capital must decrease in order to allow distributed generation to scale. As costs of capital steadily decrease, the “residual value” -- what happens to the asset once the PPA has run out -- becomes more and more important.

With that in mind, it no longer seems reasonable to fill the years after the PPA’s expiration with a row of zeros on the pro forma. There is residual value there that is often ignored.

Customers and investors often assume a negative residual value, meaning that the panels will need to be removed at the end of term at some significant net cost. In fact, there’s been a recent trend in public RFPs to require a reserve or bond for this replacement. The effect of these requirements is to raise the cost of solar to the customer -- they’re buying pricey insurance against the exceedingly unlikely event that the panels will need to be removed.

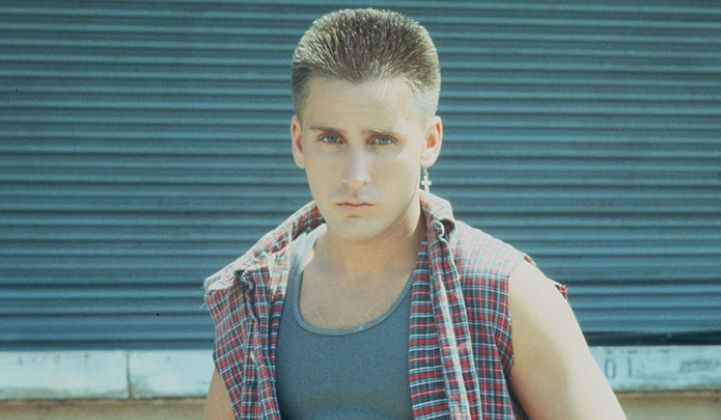

Clearly, there is not agreement on the ability to monetize an out-of-term or defaulted asset. It’s in this kind of situation that our thoughts inevitably turn to Emilio Estevez.

How Emilio Estevez relates to solar

In the 1984 classic Repo Man, Emilio’s character, Otto Maddox, becomes a repo man. (We’ll call him a facilitator working to lower costs of capital in the secured asset finance market.) Through this position, Otto “stumbles into a world of wackiness.”

Otto’s work represents something critically missing from the solar industry as a whole: a robust, standard and low-friction set of secondary industries that permit off-contract or out-of-contract assets to be monetized.

So how do we capture this real value? There are a few means of approaching it, each with radically different levels of sophistication.

To illustrate this point, let’s look at an end-of-term 1-megawatt system today and see what kind of cash it would generate to the hopeful PPA provider (or creditor) in three different scenarios, presuming that an active Otto is working on behalf of the hopeful investor or developer.

Scenario 1: The renewal -- $130,000 per MW per year

In the first and most simple scenario, the developer may leave the system in place and encourage customers to renew or extend their PPA contract at the prevailing PPA price. Most PPAs explicitly contemplate this in one way or another.

In fact, the first job of SolarCity’s investor relations team is convincing investors that their 50,000+ PPA customers will extend or renew their contracts in exchange for just a 10 percent discount of their then-applicable contract rate. Presuming a system in the Maryland area might enjoy a 10 percent to 20 percent discount to retail rates -- from say $0.13 per kilowatt-hour to $.10 per kilowatt-hour -- a renewed 1-megawatt system could add $130,000 in annual revenue.

To be clear, the level of assumption embedded in this number makes it much more debatable than the others; it’s more of an equity valuation assumption than a valid underwriting assessment. Customers at end of term will have some amount of leverage -- roughly, the delta between the discounted cash flow in the fully loaded “repo” model and whatever Otto charges the developer. (This probably contributes to the significant spread between SolarCity’s market price and analyst valuation targets.)

Scenario 2: The repo -- $40,000 per MW per year

In our second scenario, at the end of the contract term, a customer stops paying his or her PPA contract. Otto comes by to repossess the system and then plants the modules on the cheap land next to a junkyard and tow lot, selling the resulting electricity at a wholesale price. Solar panels are not perishable items (as a sort of party trick, John Perlin will happily produce from his briefcase a 40-year-old, entirely functional mini-module). Even though a 20-year old panel will have significantly degraded performance, its value is much higher than zero.

Imagine a boneyard of matched panels, placed on string inverters on some sort of highly undesirable land. On an 8,760-hour adjusted basis, a brand new 1-megawatt system airdropped into the PJM market would earn something like $56,250 per year in pure wholesale revenue; an end-of-life system operating at perhaps 80 percent of initial output should still garner more than $40,000. Revenue could be more than $50,000 if PJM doesn’t make its proposed disastrous modifications to the wholesale market.

That’s revenue that could be reliably expected to increase in the future (and while the ITC would be long gone, the new owner would be able to restart depreciation on their purchase price).

Of course, someone would still need to erect racking and string inverters, plant hedges around the motley array, handle wholesale market scheduling, feed the guard dog, etc. But these are (mostly) fixed startup costs associated with the single facility; the marginal megawatt still makes a great deal of sense.

In sum, solar still has the potential to generate significant value, even if the modules are removed from the roof after the expiration of the PPA.

Scenario 3: Scrap-hauling -- a one-time payment of $30,00 - 50,000 per MW

If Otto decides to just take the modules to the scrapyard after removing them from a customer’s roof at the end of the contract, the scrap steel in a typical ground mount array (roughly 275,000 lb per megawatt) would fetch $30 - $50,000 per megawatt in today’s market. This is enough to pay for three month's work by four construction laborers, some 15 x 30 yard dumpsters for the (nonhazardous) panels, and a fair amount of grass seed.

Customers anxious about removal or restoration of the system should just preserve the right to an abandoned system; escrowing funds for what should be a positive-cash flow removal just increases end user PPAs to insure against an unrealistic risk.

Why you should pay attention to the residual value of solar

As the weighted age of end-of-term assets increases, the opportunity to build a business in the space becomes more concrete. (Consider the fact that some of SunEdison’s first PPAs have already hit their first customer buyout eligibility dates.)

Solar is still in the early days of project finance. While some of the supporting and secondary industries are robust and well established, others do not yet exist. But it is still possible and desirable to make end-of-life assumptions that are empirical, conservative and defensible, and that make a real impact on project economics -- another horizon of opportunity for solar support businesses.

***

Colin Murchie is director of project finance at Sol Systems. This piece was originally published at Sol Systems' blog and was reprinted in edited form with permission.