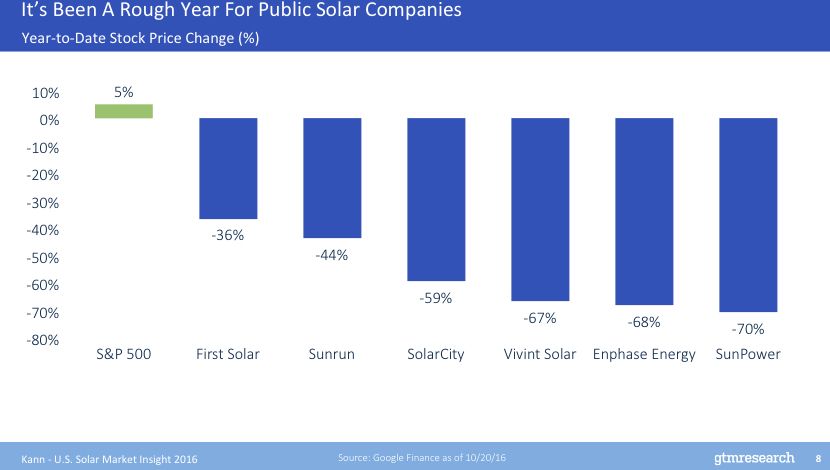

This year has been brutal for public solar companies. While the S&P 500 is up 5 percent since January, many of the leading publicly traded solar firms have faced steep declines in their stock prices, and, consequently, have initiated big rounds of layoffs.

The year also saw the collapse of ambitious developer SunEdison -- erasing a $9 billion market cap in nine months.

In his opening presentation at this year's Solar Market Insight conference, Shayle Kann provided a short list of some of the worst-performing solar companies. They happen to be some of the biggest in their respective sectors. It's not a pretty picture.

What does this chart tell us? Have investors soured on solar because they think there's something fundamentally wrong with the sector? Or have low oil prices done more damage to investor confidence than anyone predicted?

Kann asked the question bluntly: "What the hell is going on with solar stocks?"

It's neither oil prices nor an indication that investors hate solar, said Julien Dumoulin-Smith, a utility and renewable energy equities analyst at UBS. It's more specific to company strategies and sectoral pressures.

"It’s really discrete subjects pertaining to each of these companies," said Dumoulin-Smith, speaking to Kann at the SMI conference this morning. (Subscribers to GTM Squared can access the full conversation here.)

SunEdison's failure was simple. It was financial mismanagement and overreach. "What happened [with SunEdison] is no different than other companies that have seen their demise -- it's leverage," said Dumoulin-Smith.

That's completely different from companies like SunPower or First Solar -- or any other solar manufacturer, for that matter -- which are facing intense pricing pressures due to a module oversupply. Between the fourth quarter of 2015 to the end of 2017, GTM Research expects U.S. module prices alone to drop nearly 50 percent under a base-case forecast.

"I think that one is at its core the clearest. That's a pricing issue right there," said Dumoulin-Smith.

After the extension of the federal Investment Tax Credit, SunPower and First Solar have also adjusted guidance for power plant development downward as the urgency to complete projects diminishes. SunPower CEO Tom Werner also blamed "irrational PPA pricing" for eroding the company's margins.

On the residential side, the problems are leverage and the rush to scale. SolarCity is the most egregious example. "SolarCity is the most levered [solar company] we've ever seen, and it's a direct result of their corporate strategy," said Dumoulin-Smith.

SolarCity's growth-at-all-costs strategy has caused problems as U.S. residential installation growth has slowed, customer acquisition costs have risen, local installers have started to offer better pricing, and the company's cash-burn rate accelerates.

Dumoulin-Smith also warned about the over-issuance of convertible bonds -- a bond that can be converted into stock. Although convertible bonds look like a stock issuance, they pile on debt if holders decide not to convert them into equity.

"Renewable energy companies tend to use convertible bonds and treat them as a share issuance. This is what levered SolarCity," he said.

Convertible bonds have complicated Tesla's planned acquisition of SolarCity, as they may force Tesla to take on a lot more debt.

SolarCity and bankrupt SunEdison are the two biggest issuers of convertible bonds -- accounting for three-quarters of volume in the renewable energy space. "These companies think they should just be using leverage. The solar industry is so implicitly aggressive in using their leverage," said Dumoulin-Smith.

With falling equipment prices, an extension of the Investment Tax Credit, and strong net metering policy in place in a majority of states, "these should be the cream-of-the-crop days," he said.

Dumoulin-Smith believes that downstream public solar companies should reset expectations about growth and returns. "Largely, infrastructure investors are looking for a low-risk, medium-return profile. You should not expect this to be a high-return business. That’s not necessarily a bad thing."

It's only bad when the returns are low for the wrong reasons.