Peak oil is the point at which global oil production peaks and can only go down. M. King Hubbert developed the theory of peak oil after observing this pattern in individual oil fields and then extrapolating these trends to the U.S., accurately predicting a peak in U.S. production by 1970.

But in the last few years, as U.S. oil production has dramatically ramped up, many peak oil believers have been left looking a bit silly.

I’ve followed the peak oil debate for a decade and written numerous articles on this issue. There’s a good chance we will see peak oil demand arrive before a permanent peak in global peak oil production induced by physical limits.

If these events do indeed play out, we will see peak oil relatively soon. But it won’t be driven by geological or political limits on the supply side. Instead, it will be driven by an increasing array of options for reducing petroleum consumption -- lead by an ever-increasing array of electric vehicles.

I became really worried in the 2007-2008 timeframe about possible major problems from the earlier-than-expected arrival of peak oil because of the massive run-up in oil prices at that time. It was only the economic crash that began in mid-2008, the largest since the Great Depression, that led to a decline in oil prices from their record peak of $147 a barrel in July of 2008. Oil prices plummeted at that time to $33 a barrel -- more than a 75 percent reduction -- in early 2009. They climbed steadily back to over $100 a barrel in 2011 and stayed around that level until late 2014, when they crashed again into the high $20s.

The high price plateau was the highest-priced five years for oil in U.S. history, and it seemed to indicate a long-term structural shift in oil supply and demand, and thus higher prices. If there was plenty of oil to meet demand, as the “cornucopians” argued, why were prices staying so high? As the global economy climbed out of the Great Recession, it faced the strong headwinds of high oil prices.

Because oil is such a major source of energy, price swings have big impacts on the economy. For example, every $10 shift in oil prices is equivalent to a 0.1 to 0.3 percent impact to the U.S. economy. So the increase in prices from 2007 to 2008, from $56 to $147, was equivalent to a 1 percent to 3 percent GDP hit. That’s huge.

Why were prices so high until late 2014? Were we on the “undulating plateau” (to use a phrase made famous by Daniel Yergin and his company IHS) of peak oil or was something else going on?

Global supply was indeed constrained for a number of years and spare capacity was limited. This allowed disruptions in Libya, for example, in early 2011 to lead to a big price spike. Before there was such tightness we wouldn’t have seen much of a price swing from Libya’s disruptions.

This is a complex debate. But I don’t mind admitting that I was very wrong on at least one aspect: I didn’t expect to see, by 2015, the U.S. vying with Saudi Arabia and Russia to be the world’s biggest oil producer. The unconventional oil revolution here in the U.S. took a lot of people by surprise, including me.

The peak oil crowd has been silent for a while now because all those people were also surprised by the unconventional oil production spike in the U.S. and a slower-than-expected decline in conventional oil production. A lot of people who have followed the peak oil debate peripherally assume that the peak oilers were simply wrong -- way wrong -- about peak oil.

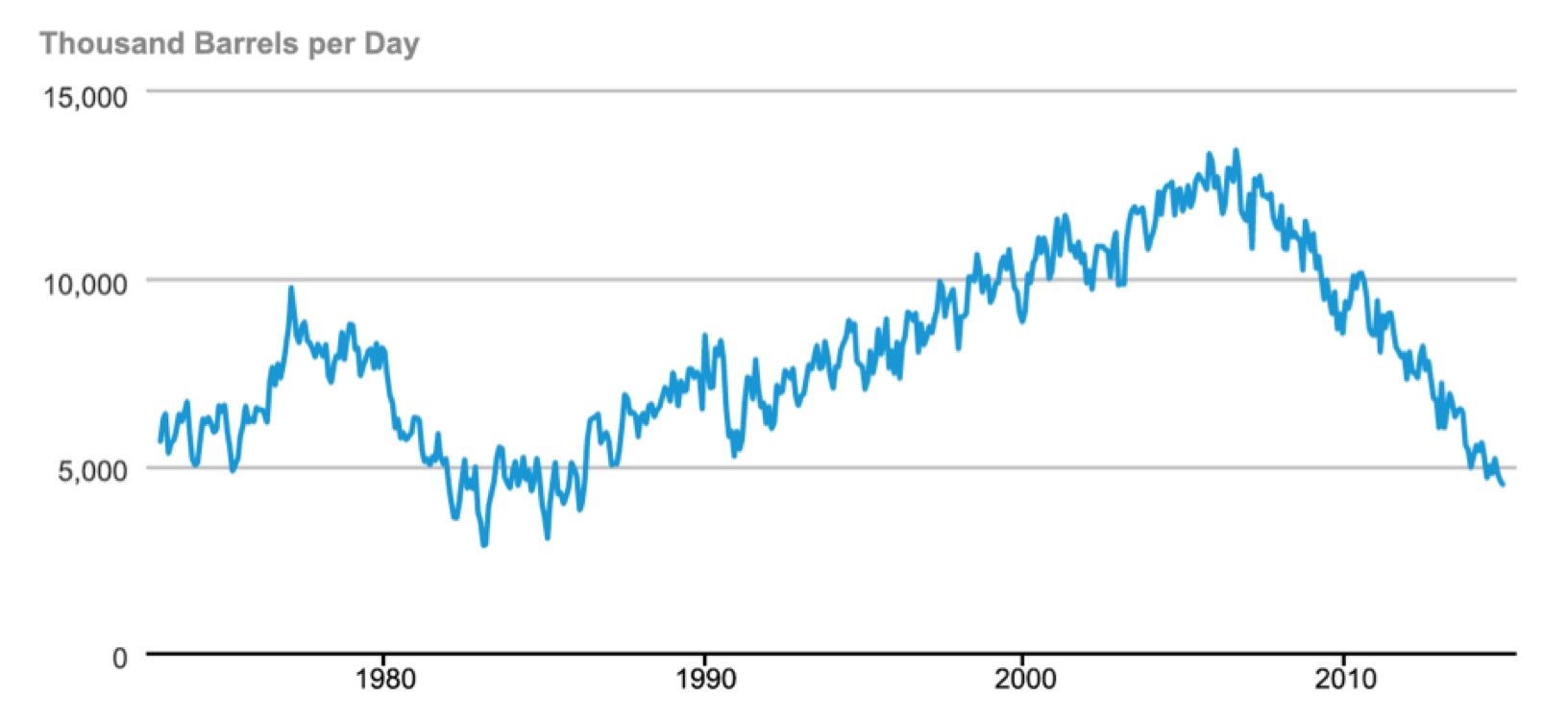

One thing at least is clear at this point in time: the U.S. has achieved a massive increase in oil production (crude oil and condensate) since about 2009, increasing from about 5 million barrels per day (mbpd) to over 9 mbpd by early 2015. This increase has brought our country almost on par with Saudi Arabia and Russia as the world’s biggest producers. When we add in other liquids production like natural gas liquids, refined products, and ethanol, the U.S. is over 14 mbpd and leads the world as a liquid fuel producer.

Figure 1: Comparing U.S., Saudi and Russian Crude Oil and Condensate Production

Source: EIA

Why is this such a big deal? Well, it shows that the U.S. was able to turn around a multi-generational decline in oil production with new technologies. And it does give pause to even the most cautious peak oilers because we now have very good proof that oil production can change, and change big, in just a few years.

Maybe there is nothing inevitable about long-term oil production declines anymore. To illustrate this point, Figure 2 shows U.S. oil production over the last 150 years, from the 1970 oil production peak to the 2015 (almost) return to that peak.

Figure 2: U.S. Oil Production Since 1860 (Barrels per Year)

Source: EIA

Globally, however, the picture is different. Fracking and horizontal drilling -- the technological breakthroughs that led to the U.S. production resurgence -- haven’t caught on around the world in the same way that they have in the U.S.

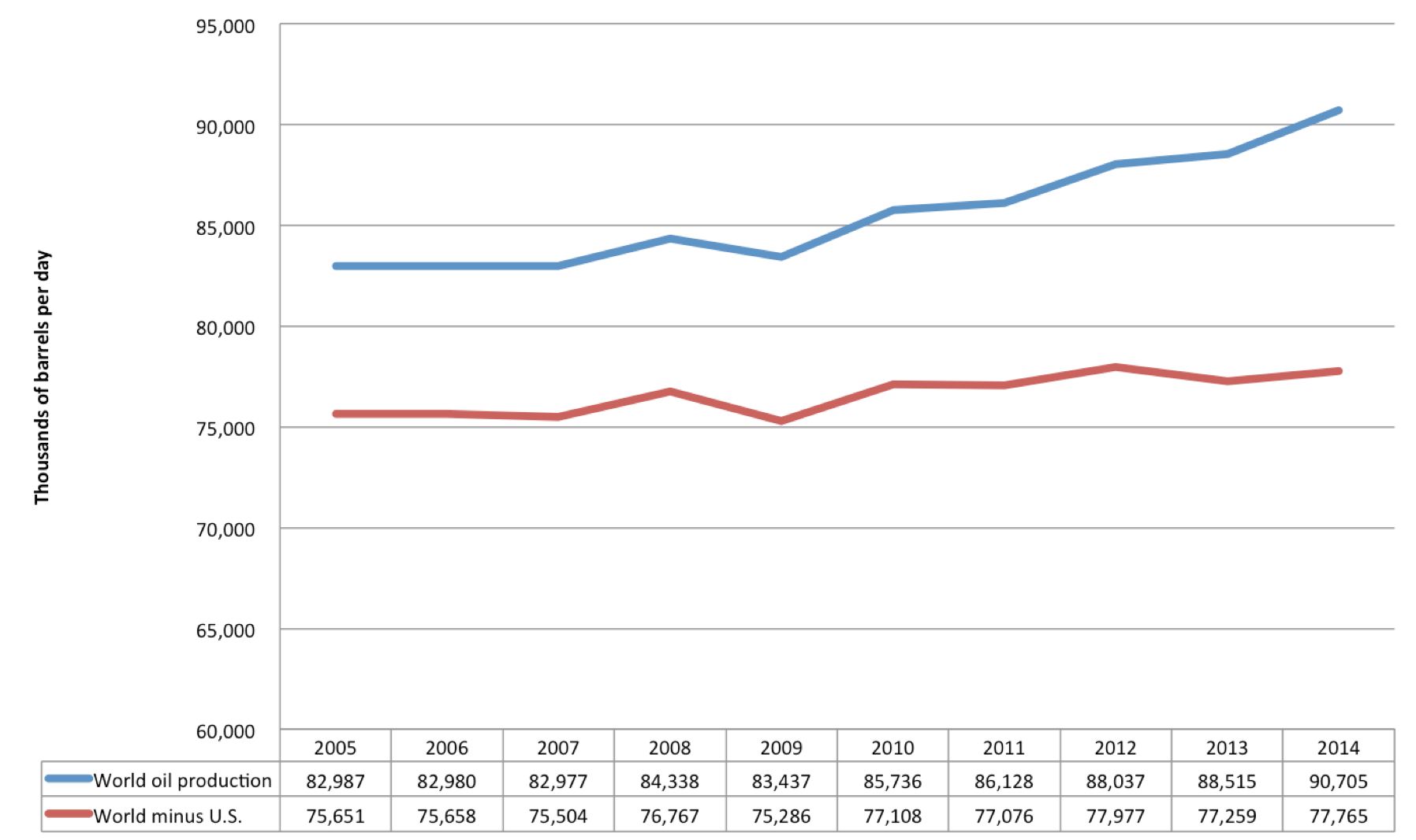

Global production is up from the plateau years of 2005-2010, but only by about 5 mbpd. This is, in fact, not much larger than the U.S. increase in production, so the global increase is largely equivalent to the U.S. increase in production. This demonstrates that global production other than the U.S. has been on a plateau for the last 10 years, at about 75 to 76 mbpd. So when U.S. production falls, global production may well fall to the same degree.

Figure 3: Global Oil Production, 2005-2014

Source: EIA

In light of these new facts, let’s examine some of the arguments behind peak oil and see if there’s still any relevance to this debate.

Do all of us peak oilers simply need to reconsider our arguments and believe more in the free market to incentivize new drilling technologies and new areas for production?

The world wakes up to peak oil?

The 2008 World Energy Outlook issued by the International Energy Agency (IEA) was the document that really got me interested in peak oil. That year, the IEA completed a supply-side analysis of the world’s 800 biggest oil fields.

In previous analyses, IEA had projected oil and other fossil fuel demand based on economic modeling and simply assumed (literally) that supplies would meet this projected demand. The 2008 WEO used a very different approach. Rather than simply assuming supplies would meet demand, IEA looked at the largest oil fields and calculated their rate of production and decline (this is what a “supply-side analysis” means). The agency found that these fields were declining far faster than previously assumed -- about 7 percent per year, rather than the 3.5 percent per year assumed earlier.

Based on this decline rate, IEA calculated that the world would need eight new Saudi Arabias by 2030 to meet projected demand. In the medium term, it projected a likely “oil supply crunch” by 2015 because we’d need three to four new Saudi Arabias by then to meet projected demand. We know now, of course, that no supply crunch came by 2015. To the contrary, we have seen at least here in the U.S. a major swing back to increased production.

At the time of this writing, the West Texas Intermediate price was about $40 a barrel and Brent was priced around $42 a barrel. Prices are up about 40 percent from recent lows, but still well below the $100 or so average price since 2010.

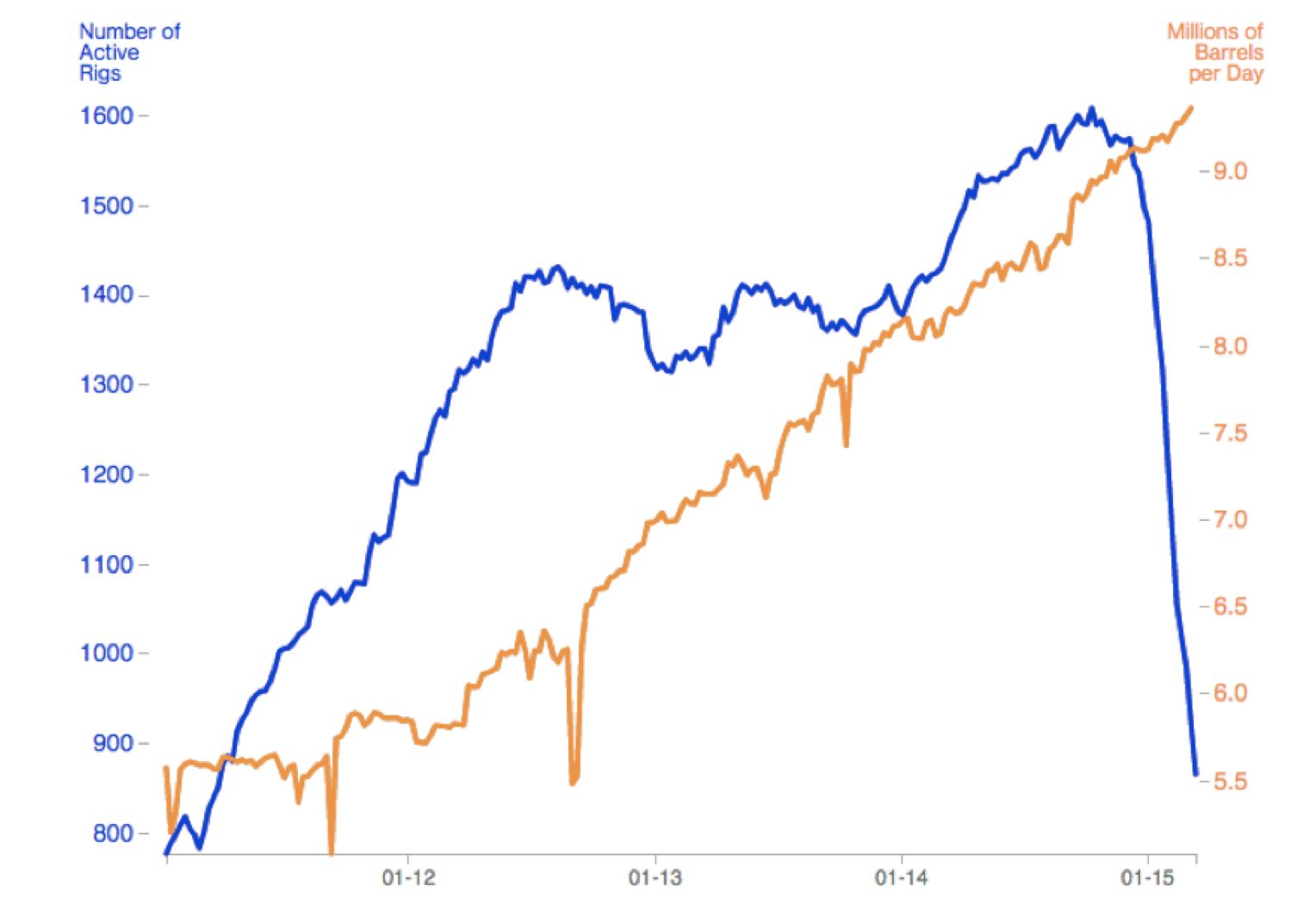

We have likely reached a bottom in oil prices now, and many observers expect prices to rise significantly. We’ve seen the number of oil rigs in the U.S. plummet in response to these much lower prices and reach 70-year lows. This is a major leading indicator of a coming dip in oil production in the U.S.

Figure 4: Active Oil Rigs vs. Production

Source: Bloomberg

The coming dip in production will not be driven by physical limits on production capacity. Rather, the drop will be due to the lack of economic viability of unconventional oil in the relatively low price environment we’ve seen over the last year and a half. Even though this is a real limit, the difference between this kind of economic limit and physical resource depletion is that once prices rise again, we may see a lot of the retired production come back on-line relatively rapidly. What it does illustrate, however, is the very real trend toward higher production costs as the “easy oil” is depleted around the world.

As we’ll see below, the new global oil dynamic may be defined by peak demand rather than physical limits on production. But any peak in global demand will depend very much on the degree to which EVs and other petroleum-use-reducing technologies are adopted. It’s too early at this point in the game to say how this will unfold.

What do we know with certainty?

While the timing of peak oil (whether in terms of physical production limits or peak demand) will always be uncertain, there are a few things about this debate that we can know with relative certainty. For example, we know that oil is getting harder and harder to find, which is why new drilling techniques are being invented and so many new drilling platforms are going into deeper water and more remote areas of the world.

We also know that the oil majors are spending more to produce less oil and add less to their oil reserves. A February 2015 Reuters analysis found the following: “Over the past decade, the biggest Western oil companies have seen reserves growth stall, production drop 15 percent and profits fall by almost a fifth -- even as oil prices almost doubled, a Reuters analysis of corporate filings shows.”

Similarly, the respected industry news site oilprice.com ran an article in early 2015 that described a possible major increase in global oil prices in the next decade, since 2014 was the fifth year in a row that oil majors failed to replace their oil reserves with new discoveries.

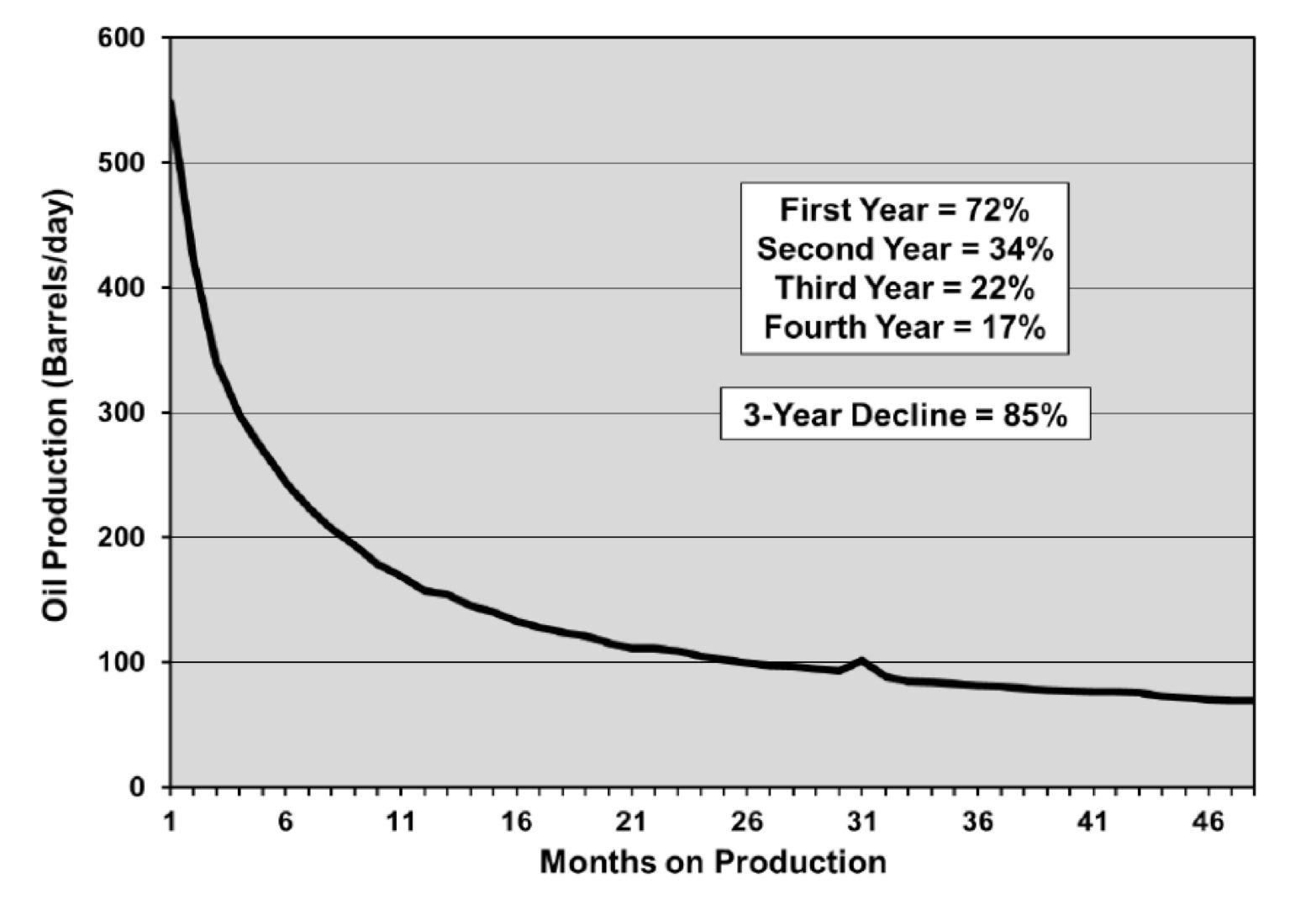

We also know that unconventional oil wells have far higher production declines than conventional wells. Oilprice.com also reported on a new analysis by David Hughes and the Post-Carbon Institute predicting an earlier and stronger decline for U.S. oil production resulting from higher-than-normal decline rates in new wells.

The average decline rate for conventional wells is about 5 percent per year. In stark contrast, the average decline rate for fracked and other unconventional wells is 60 percent to 91 percent over the first three years, at which point declines slow down in an extended but low level of production. The obvious result of these high decline rates is the need to drill more and more new wells to make up for declining production.

Figure 5: Analysis of Average Decline Rates for Tight Oil Production in the Bakken Formation

Source: Post-Carbon Institute

We also know that oil-producing nations often see steadily rising demand for the resource combined with long-term production declines, leading eventually to zero oil exports from these countries. This is a phenomenon that has already happened with dozens of former oil-exporting countries.

This is probably the biggest issue in the peak oil discussion. Even if global oil production continues upward for some time, for oil-importing countries like the U.S. and almost all of Europe, what matters is not global production but global net exports -- available oil, in other words. Even with the resurgence of U.S. oil production, we still import about five mbpd (about 25 percent of our demand), equivalent to about half of Saudi Arabia’s entire exports.

Figure 6: U.S. Net Oil Imports and Petroleum Products

Source: EIA

I focus on Saudi Arabia next in order to highlight the net exports issues. As U.S. demand increases and our oil production plateaus and declines, it’s likely that we’ll see our net imports figure rise substantially again.

The Saudi oil problem

Saudi Arabia’s national oil company, Saudi Aramco, pumped about 11.5 million barrels per day in 2014, up from about 9.5 million in early 2009. The Saudis are pumping more oil now than they have in decades, along with the rest of OPEC, which is at almost a 25-year high for combined oil production.

Russia held the top spot for oil production for a couple of years, but Saudi Arabia has come roaring back since 2010. The U.S. is in third place with about 9 mbpd.

Net oil exports, are, however, a different picture. The U.S. was for some time the world’s biggest importer of oil, before being surpassed in 2014 by China. While our production of oil has trended upward in the last few years, and our consumption of oil has declined due to increased energy efficiency, conservation and a still-struggling economy, we still import about 25 percent of the oil we consume.

Saudi Arabia exports about 8 mbpd, with Russia not too far behind at about 7 mbpd.

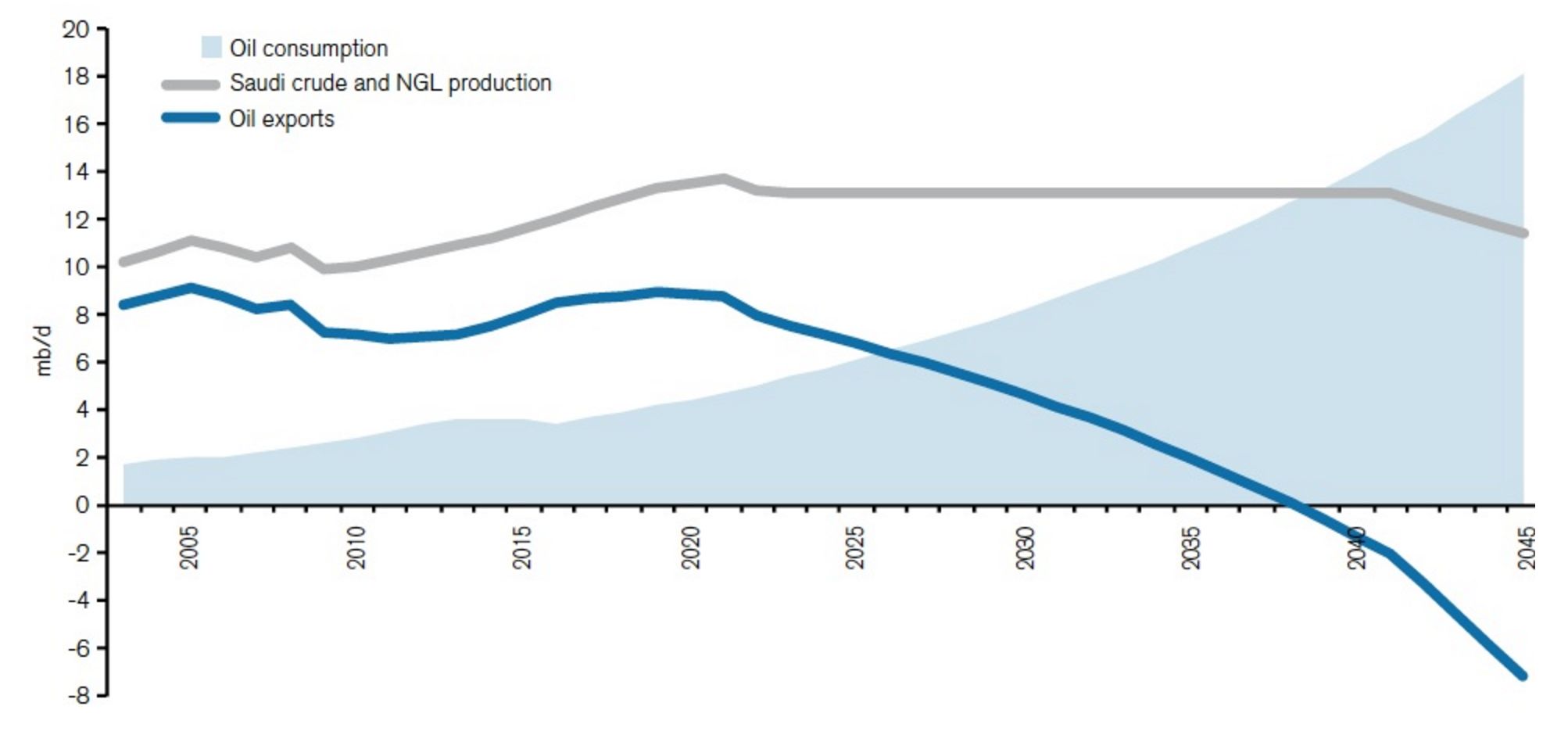

This is all fairly familiar data. However, the degree to which Saudi Arabia’s massive oil exports are threatened by its demographics and a probable decline in its aging supergiant oil fields -- particularly from 2020 onward -- is not well known.

A 2011 report from the U.K.’s Chatham House examined this problem in detail. It concluded that Saudi Arabia’s oil exports will peak around 2020 and, under current policies, decline to zero by 2038. You read that right: decline to zero.

This decline will occur due to the dramatic growth in consumption by Saudi Arabia’s rapidly growing population and increases in per capita energy consumption. Saudi domestic consumption of oil is growing at about 7 percent per year, which leads to a doubling of consumption in just 10 years.

Figure 7: Saudi Arabia’s Oil Balance Under “Business as Usual” Projections

Source: Chatham House

Saudi Arabia’s growth in consumption in the last few years hasn’t been as high as the Chatham House report forecast. EIA has data through 2013, and the growth in consumption for 2010-2014 averaged 4.0 percent rather than the 7 percent that Chatham forecast.

However, the 7 percent figure is an average growth rate through the 2045 forecast period. As is clear from the previous chart, the oil consumption curve heads up steadily from 2016 onward, but Chatham House actually forecasted a slight decline in consumption from 2012-2016.

Saudi Arabia’s problem is not, of course, unique to Saudi Arabia. It is a global problem that afflicts most oil-producing countries, because wealth from oil spurs economic growth, which in turn spurs increased consumption of oil. Jeffrey Brown and Samuel Foucher, an oil geologist and mathematician, respectively, have developed an “Export Land Model” to predict how the global net oil export situation will unfold in coming years.

Brown’s analysis through the end of 2012 found that the top 33 oil exporting countries will steadily see their exports shrink to a ratio of about 2:1 for production vs. consumption by the early 2030s. And by 2030, Brown projects under current trends that all available net exports will be consumed by China and India alone due to their strong rates of economic growth.

Brown’s net oil export projection declines are due to the demographic explosion that the Chatham House report focuses on -- but also due to declines in oil production in exporting nations. Chatham House chose not to discuss the role of declining oil production, and instead chose to believe Saudi projections of steady or growing oil production. However, declining oil production is a real and extremely serious corollary to the demographic explosion. It’s also the reason why Brown and Foucher project Saudi Arabia and other oil exporters going to zero faster than the Chatham House report predicts.

Can the shale oil revolution take off outside of the U.S.?

In sum, it seems that the debate about peak oil -- to the extent that it still exists today -- rests on the degree to which fracking and horizontal drilling techniques can be used outside of the U.S. to expand global production, and the degree to which potential increases in production can offset the declining global net oil exports.

Iraq is also a big unknown in terms of its ability to ramp up production. By all accounts, it has the resources to ramp up production substantially. But with the turmoil being caused by Daesh/ISIS in that country since 2014, it is highly unlikely that Iraq will come to the rescue in time to make up for the coming decline in U.S. unconventional oil production.

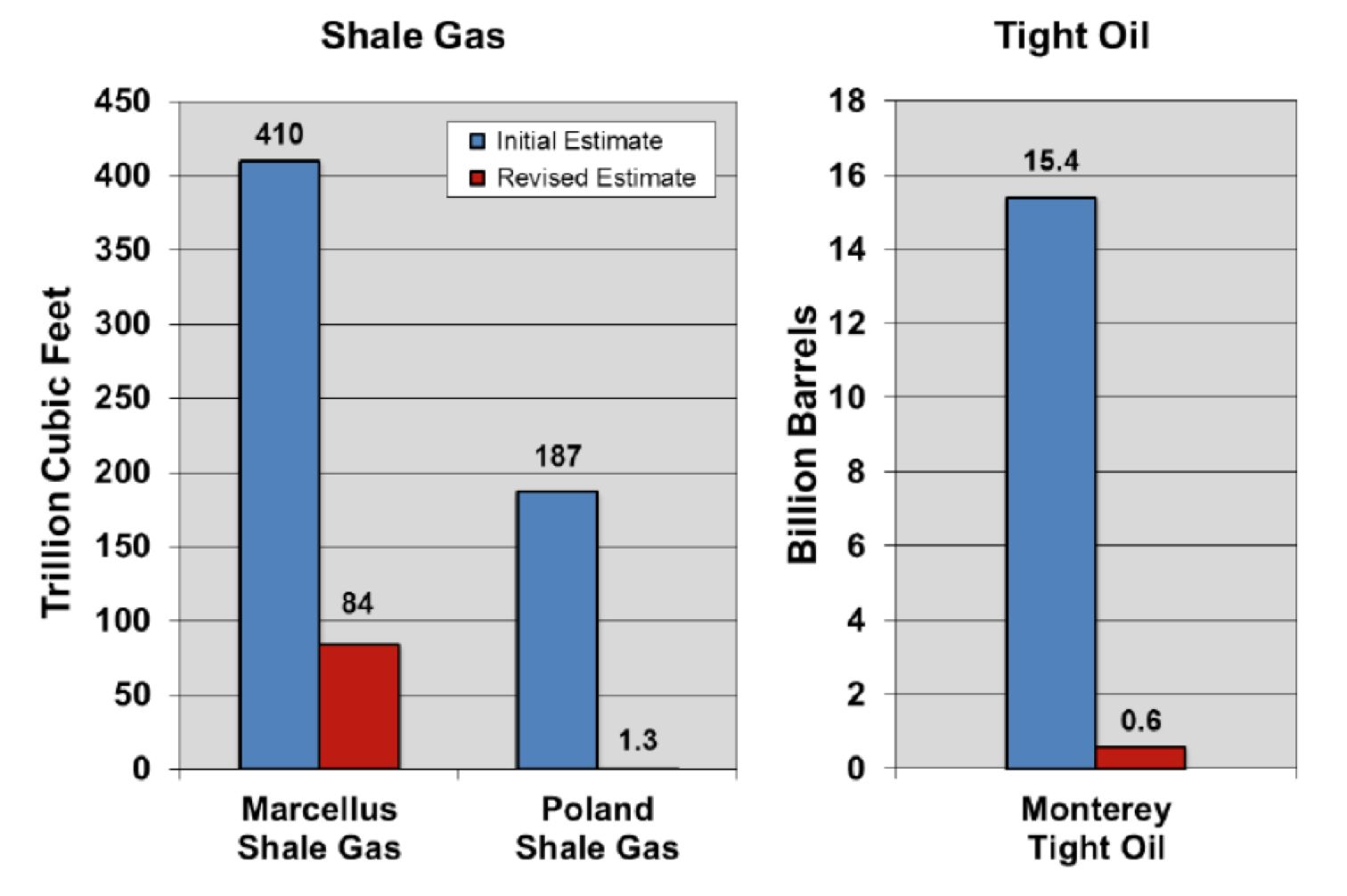

The perils of assuming that other shale oil resources are suitable for oil fracking is illustrated by the early 2014 downgrade of oil resources in California’s Monterey Shale formation. EIA projected, before this downgrade, that the Monterey Shale contained almost 14 billion barrels of recoverable oil, a large share of the nation’s remaining oil resources. The 2014 revision reduced this figure by 96 percent, in line with a new survey by the U.S. Geological Survey.

Similar downgrades have taken place for shale gas. The Marcellus Shale in the Eastern U.S. was downgraded by 80 percent and a formation in Poland was downgraded by a whopping 99 percent.

Figure 8: EIA Downgrades of Shale Oil and Gas Resources

Source: Post-Carbon Institute

EIA and IEA project, in their 2014 reference cases, that U.S. unconventional oil production will peak around 2020, with total production leveling off at around 10 mbpd through the early to mid-2020s. If the fracking revolution can’t be exported outside of the U.S., it is likely that we’ll see global production decline in the same timeframe: the early 2020s.

Declining U.S. unconventional oil production five to eight years from now has IEA’s chief economist, Fatih Birol, scared. He has stated in various forums his concern about current low prices inducing an unwarranted complacency about long-term oil supplies. Low prices have already induced a major tumble in oil rig deployments in the U.S., as we saw above, setting us up for a big dip in oil production.

There’s also a possibility, however, captured in the EIA “high oil and gas resource” case in the 2014 Annual Energy Outlook, that U.S. oil production will continue to climb through the 2020s and 2030s, peaking around 13 mbpd. This increase in production, if it occurs, will surely help exert a long-term downward pressure on oil prices. But given the very high decline rates of fracked wells, it seems more likely that we’ll see U.S. and global demand decline substantially in this timeframe, exerting the same downward pressure on prices. It is this idea -- a peak in global oil demand -- that I turn to next.

But what about peak demand?

The peak oil debate has taken an interesting turn. It seems now that we may hit peak demand before we hit peak oil (in terms of physical production limits). By "peak demand," I mean the globe may see a permanent decline in oil demand before we hit long-term physical production limits. If this is the case, the cornucopians will have been proven right -- not the peak oilers. Time will tell.

Why would we see a decline in demand any time soon, with the developing world population and consumption still growing strongly? As I’ve described in previous columns, exponential growth in electric vehicles and steadily declining costs may well lead to a relatively rapid transformation in how we move people and goods in the coming two to three decades.

We can’t at this point make any firm predictions about sales of EVs even in the next few years. But we are seeing a classic learning curve with EV technologies that suggests a coming boom in EV sales. The real game-changers will be the pending crop of 200+ mile range EVs, including Tesla’s planned Model 3, the Chevy Bolt, the new and improved Nissan Leaf, VW’s planned 300+ mile range car, and probably many other manufacturers already plotting developments in this space. Once these cars are available and affordable, we may well see the exponential growth curve turn sharply upward. Globally, we’re seeing a very robust sales growth trend continuing.

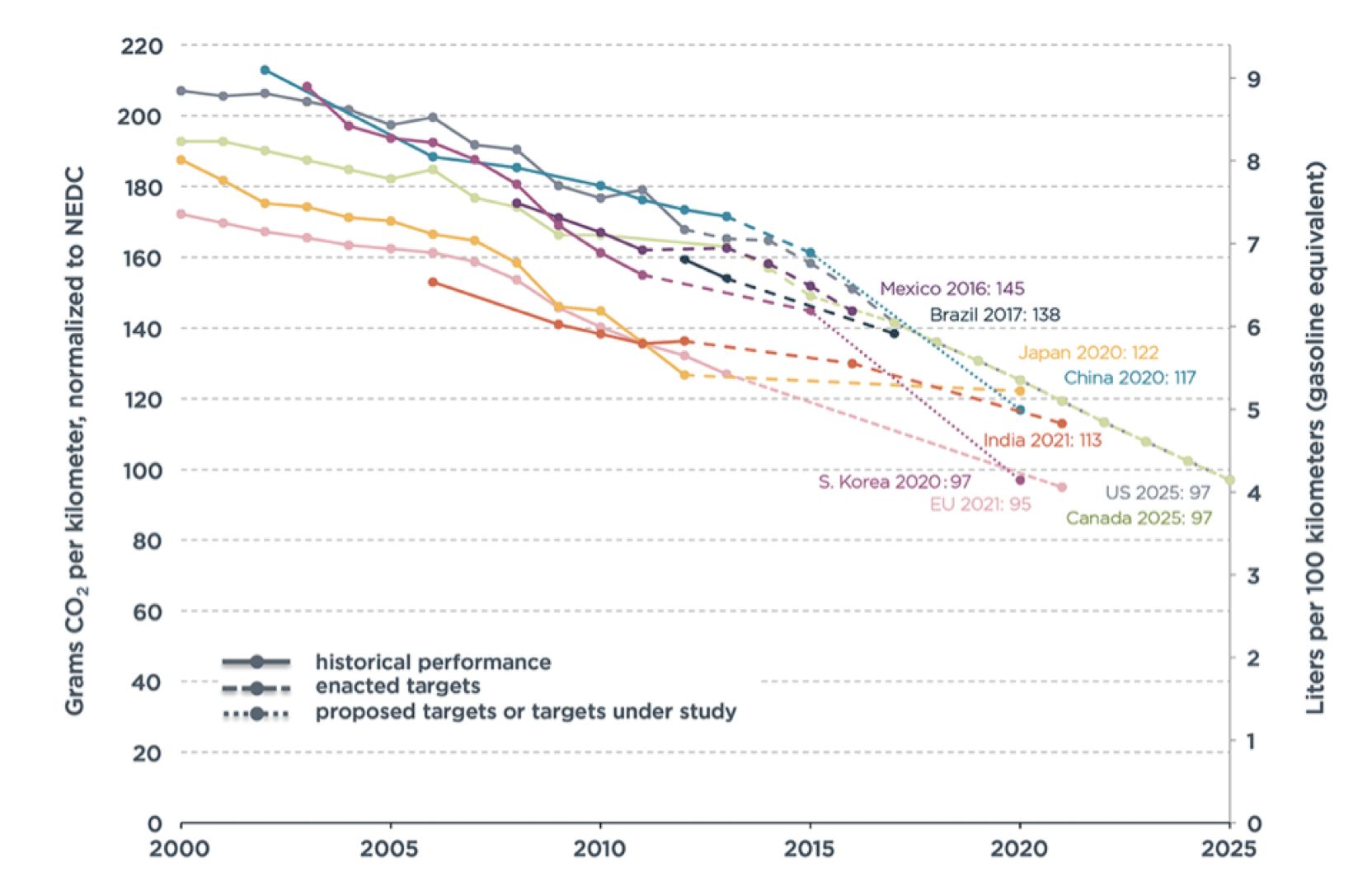

Independently of EVs, we’re also seeing many other technologies leading to lighter and more efficient cars. Some kind of fuel economy standard is in place now for 80 percent of the world’s passenger vehicles sold in 2013, according to the International Council on Clean Transportation.

The general trend is toward cutting emissions from passenger vehicles by half between 2000 and 2025. We’re about halfway to achieving that goal. And it is realistic to expect that the 2020-2025 goals will be met due to the many new technologies arriving that will improve fuel efficiency and decrease GHG emissions.

Figure 9: Vehicle Fuel Efficiency Standards for Various Countries

Source: ICCT

EIA projects in its 2015 World Energy Outlook that oil demand will rise to 104 mbpd by 2040, up from 91 mbpd in 2014. This is a significant increase, but it’s a large decline from previous forecasts -- reflecting the increasing role of improved vehicle fuel efficiency around the world. We can anticipate that we’ll see additional vehicle fuel efficiency gains materialize in the coming years. We also have forecasts from China’s oil companies that suggest that China’s oil demand will peak far sooner than the IEA and others currently project.

An early 2015 forecast from Sinopec projects that gasoline and diesel demand will peak by about 2025 in China. If China’s development curve is mirrored by other major emerging economies like India and Brazil, we may well see peak demand before peak oil.

In 2014, China saw a 220 percent increase in EV sales, and a 223 percent increase in 2015, for a total of 189,000 EVs sold. China has shown, with its very serious growth in solar, wind, hydro and nuclear, along with coal power plants, that it is capable of ramping up deployment of new technologies very quickly.

Although Chinese EV sales make up about 1 percent of total vehicles sold, the country is now the world’s largest EV market. Current rates of growth suggest that China will continue to lead the world on the EV transition, as it is now leading the world on the renewable energy transition. This trend will have a direct impact on China’s oil consumption.

Global oil demand, however, depends on far too many factors to make any confident predictions at this point. But we can see a plausible future in which global oil demand peaks in the next decade due to major improvements in petroleum alternatives and due to ongoing conservation and efficiency efforts. If this does happen, we may actually be able to avoid the disruptions that would come from cyclical oil price spikes from inadequate supplies.

***

Tam Hunt is a lawyer and owner of Community Renewable Solutions LLC, a renewable energy project development and policy advocacy firm based in Santa Barbara, California and Hilo, Hawaii, co-founder of Solar Trains LLC, and author of the new book, Solar: Why Our Energy Future Is So Bright.