At the end of June, Washington state had 24,624 plug-in electric vehicles registered. Most were in outlying areas of Seattle, with King County accounting for over half those vehicles.

The distribution remains more sparse in the eastern part of the state. Some of those counties overlap with the service territory of Avista Corporation, a utility with natural gas and electric operations in Washington, Idaho and a few pockets of Oregon. Avista estimates there are just 600 electric vehicles in its Washington territory.

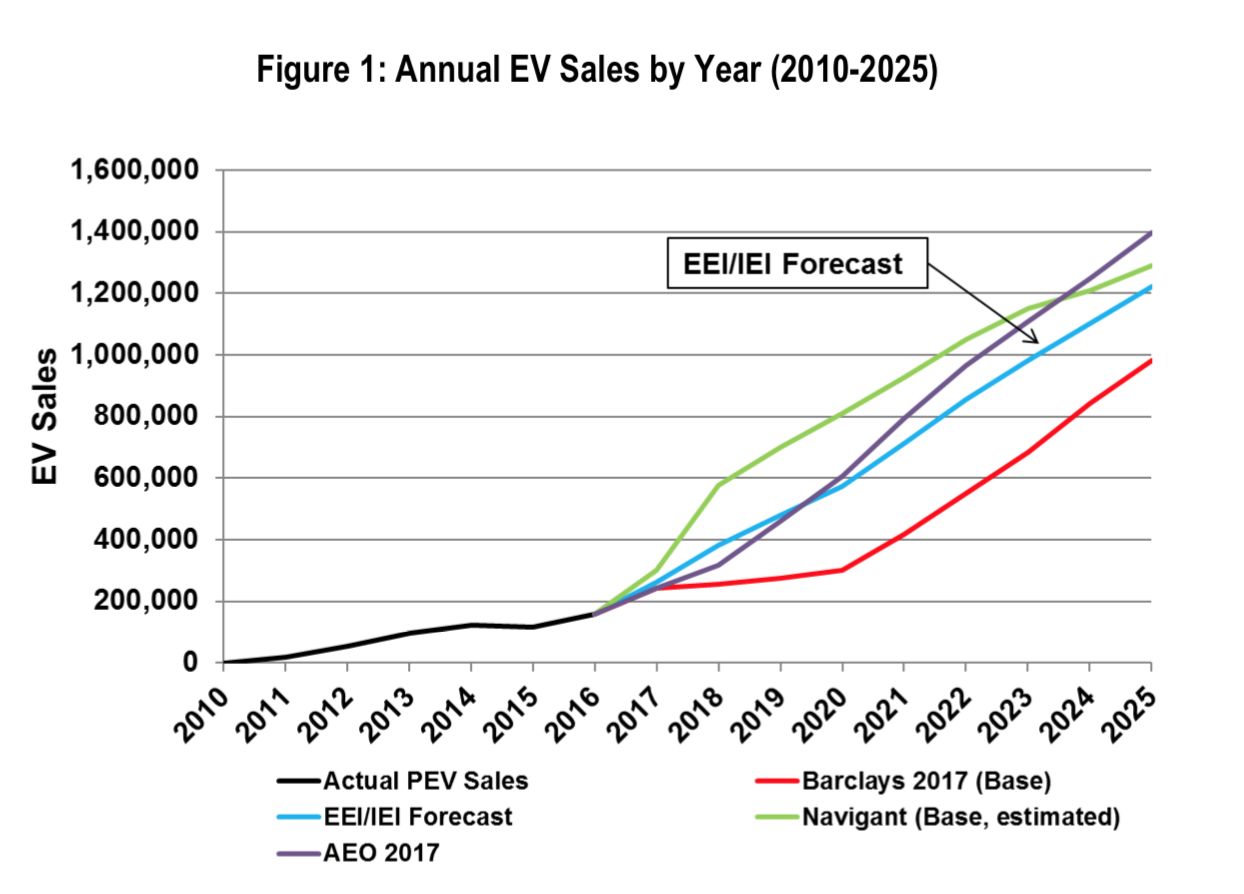

But that doesn’t mean the utility isn’t preparing for an electric future. According to Avista, the utility is seeing growth of about 30 percent year-over-year. Edison Electric Institute, which represents the country’s investor-owned utilities, projects the entire U.S. will have 7 million EVs by 2025.

Source: Edison Electric Institute

“We see it coming, but there are a lot of uncertainties,” said Rendall Farley, manager of electric transportation at Avista. “Our overall stance and our road map looking ahead is that this is going to be potentially a very important way to better serve our customers in the future. It’s our responsibility to manage the grid the best we can.”

In 2016, the Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission approved Avista’s pilot EV charger program, later extending it through June 2019. The extended initiative -- which Farley said is small compared to those in California, but the right size for the utility's territory -- includes a maximum of 240 residential chargers, 175 at workplaces, 60 public sites installed on commercial property, and 70 DC fast-charging stations. All of the chargers are Avista-owned and -managed.

The pilot came on the heels of 2015 state legislation that declared utilities “must be fully empowered and incentivized to be engaged in the electrification of our transportation system.”

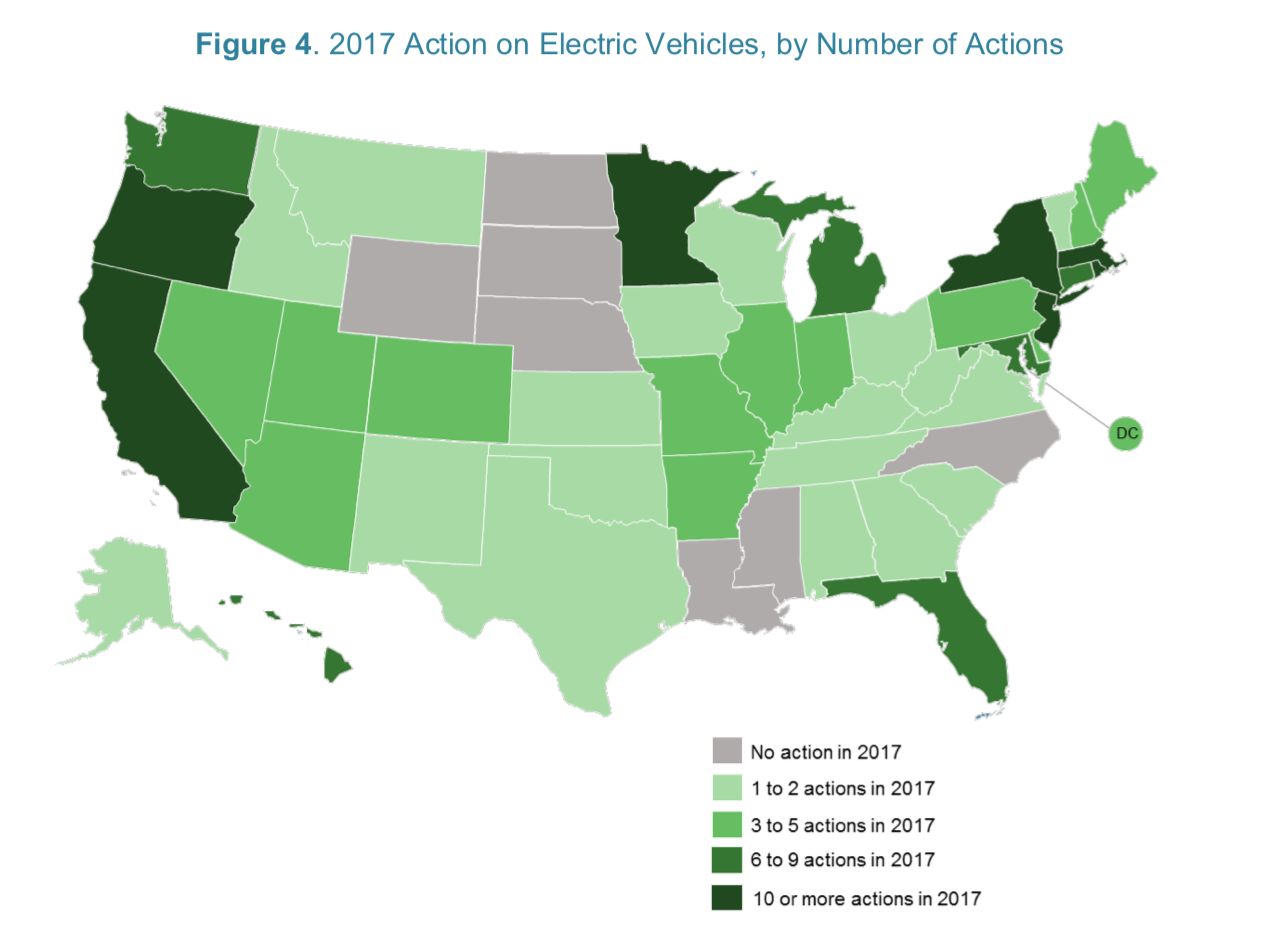

The experimentation in Washington echoes similar efforts around the country. According to a February white paper from the Edison Electric Institute and a February report from the NC Clean Energy Technology Center at North Carolina State University’s College of Engineering, utilities continue to take seriously the projections of mushrooming EV uptake. In 2017 the NC Clean Energy Technology Center tallied 227 actions related to electric vehicles in 43 states and Washington, D.C., many undertaken by utilities.

Source: NC Clean Energy Technology Center

By their measure, Washington was the 10th most active state, with a focus on incentives and market development. Those actions include the extension of Avista’s program.

Farley said part of the reason the utility wanted to extend its trial was to squeeze more out of its learning objectives.

“We proposed the program in a way that was based mostly about learning,” he said. “For the utility, this would position us to understand how EVs would impact the grid and how we could potentially shift people into off-peak [charging periods] in the future, and still keep customers happy.”

Charging infrastructure -- or the perceived lack thereof -- remains a persistent barrier to rapid uptake of EVs. It's one that utilities may be uniquely positioned to tackle.

“The organizations that are in the best position to provide [infrastructure access] are the utilities, because their mandate is to serve the public interest,” Brett Hauser at Greenlots, which partnered with Washington on its pilot, told GTM in November.

In its white paper, Edison Electric Institute also noted that a utility’s role in managing the grid, as well as “existing relationships with customers,” puts electric companies in a particularly advantageous position to help proliferate charging.

That close customer relationship is one reason why Avista chose to own its chargers.

“That allows us to give the customer peace of mind that there’s someone they can trust doing a good job, getting installation done,” said Farley. “If anything goes badly with the charger, they don’t have to worry about it.”

At the same time, though, Farley said he doesn’t think the Avista model of ownership and management, with sites managing wiring upgrades, is the only viable approach. He said utilities need a variety of business models -- “the more the better” -- to determine what works for customers and a particular region’s load and demand. In other pilots, like those in California, utilities are using a variety of ownership setups.

A mix of business models, according to Farley, will allow utilities to more fully understand how customers are using chargers -- the key goal of the Washington pilot.

The same motivations apply in understanding the grid impacts from EVs.

Avista initially networked chargers to get “a 360-degree view of charging behavior,” but did not control them. The utility is now moving to a demand-response-like model to shift customer behavior unless they opt out. Farley said the utility suspects it can shift 75 percent or more from peak charging load to off-peak without using time-of-use rates or other incentives.

The NC Clean Energy Technology Center report noted that last year 11 states and Washington, D.C. proposed new rate schedules or changes to existing rate schedules for EVs, including a December proposal from Avista to change DC fast-charging rates from a flat 30 cents per minute to time-dependent rates. Four states introduced bills that would create tariffs to compel off-peak charging.

In Washington, the state aims to have 50,000 plug-in vehicles on its roads by 2020, a near doubling of its current registrations in just two years. But Farley said Avista will be there to assist.

“We believe this is the future of transportation,” said Farley. “It behooves us to learn how we can best serve the customer.”