A set of pipes running nearly two miles out into Lake Ontario are part of a novel project to help Toronto Hydro extend the life of its distribution equipment.

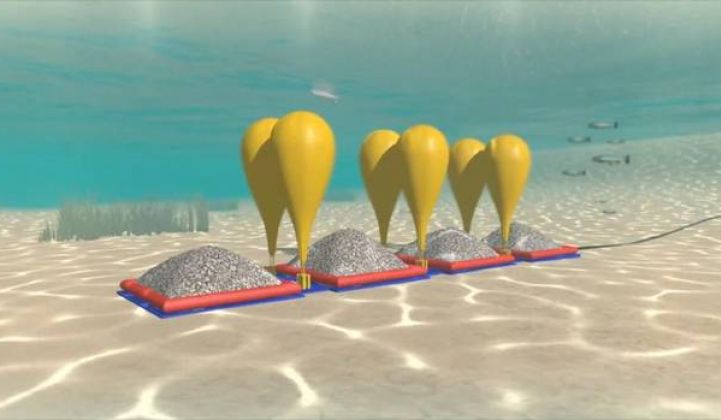

The two-year pilot is not another tidal energy project -- it's the first test of an underwater compressed-air energy storage system by Ontario-based startup Hydrostor. The company uses off-the-shelf technology to pump air into underwater balloons. When energy is needed, the air can be released from balloons and expanded to create electricity.

The pilot project will help Toronto Hydro defer distribution investment by providing peak electricity. But the near-term market opportunity for Hydrostor is in displacing backup and peak generation sources like diesel or coal. Depending on the success of the Toronto pilot in the next few months, Aruba also has a pending contract for Hydrostor’s technology.

“We are able to work more like a developer,” said Curtis VanWalleghem, CEO and co-founder of Hydrostor. “We can make a brisk business doing a few projects a year.”

By not manufacturing anything, VanWalleghem said Hydrostor’s costs are far lower than other compressed-air energy storage startups, such as LightSail.

The company uses drilling techniques that reduce the demand for boats and cranes at the surface to deploy the pipes and balloons. VanWalleghem said the installation of the underwater balloons, which are slight modifications of the ones used for marine salvage, requires only one tugboat. Although Hydrostor has streamlined the installation and reduced costs, it requires some serious permitting. The pilot in Toronto, for example, required 17 permits.

Back on land, electricity runs a compressor to produce the compressed air. During that process, waste heat is captured and could be used to increase the round-trip efficiency from about 60 percent to as high as 80 percent.

The compressed air is pressurized to match the pressure at the ocean floor where the balloons are located. The air is then pumped down to fill those balloons. When electricity is needed, the system goes into reverse mode and the weight of the water pushes the air back to land, where it is converted back into energy.

The balloons will come with at least a 10-year warranty, and that could be expanded to up to 20 years after the pilot.

If Hydrostor can prove itself, it sees opportunities not only on islands, but also in fast-growing coastal cities, especially in Asia. The pilot will also assuage potential clients and investors asking about marine environment impact and potential threats to boaters. VanWalleghem said the technology is not a threat to marine animals or boating traffic, and has a track record from years of use by maritime and oil and gas industries.

The Toronto pilot is a 1-megawatt project, but Hydrostor will offer larger storage, including a 5-, 10-, 50- and 100-megawatt option if fully commercialized. At 10 megawatts, the cost would be about $250 per kilowatt-hour, said VanWalleghem. That would make it far cheaper than the full cost of compressed-air energy storage on land.

The cost is dependent on how deep the water is close to shore. In Toronto, the balloons sit about 180 feet deep and about 1.8 miles offshore. The price of the base design is based on a depth of about 650 feet at 1.8 miles offshore.

Because the energy storage solution is dependent on specific water depths, Hydrostor is currently mapping offshore water depths, local power prices and transmission constraints to identify ideal markets. “We have a list of target islands,” he said.

The company has raised about $5 million to date through a seed round and a Series A round funded by ArcTern Ventures. The Canadian startup is also in talks with global engineering, procurement and construction firms with the goal of a strategic partnership.