Citigroup (NYSE: C), Credit Suisse (NYSE: ADR), Citigroup, and other financial architects are reportedly working on the securitization of leases held by third parties on residential and commercial solar installations.

Will institutional investors' buy into bonds backed by the assets the solar leases represent turn out better than the mortgage-backed securities fiasco that led to the global financial crisis?

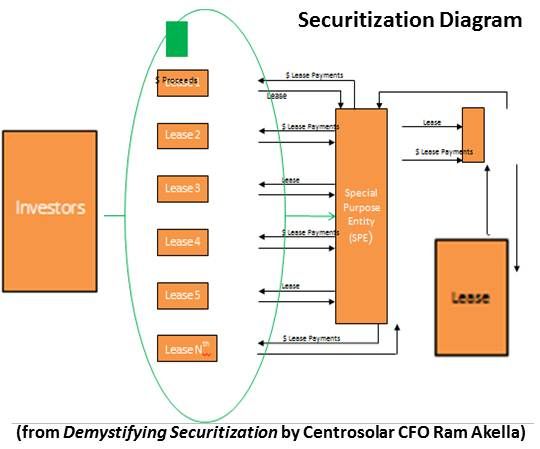

“Essentially, you’re your asset base, a portfolio of leases,” explained Centrosolar America CFO Ram Akella,“slicing and dicing cash flow and issuing bonds secured by those cash flows to institutional investors who are willing to invest money at a very low rate of return because they are high-credit-quality bonds.”

Securitization, Akella said, is “a subset of third-party ownership” because, though ownership shifts from leasing companies like Sunrun and SolarCity to institutional investors, “it is always the third party who owns the assets.”

The “portfolio of assets,” Akella said, referring to the solar companies’ leases, “goes through modeling, structuring, legal, financial -- the whole nine yards to create a financial product as risk-free as possible.”

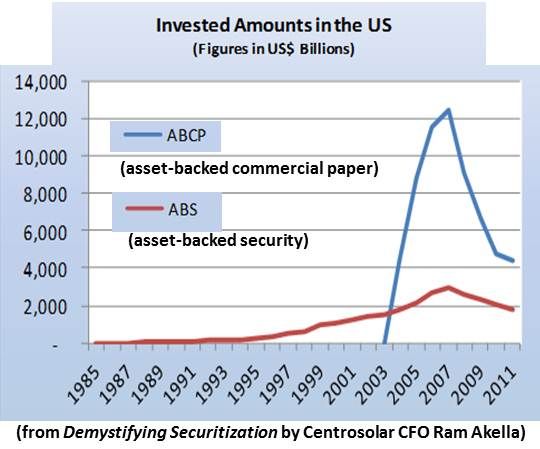

Securitization has not yet been done in solar, Akella said. Analysts expect such a deal as early as the beginning of 2013. It has been used since the 1970s, he explained, in asset classes like equipment leases, car loans, car leases, residential mortgages, commercial mortgages, and commercial loans.

Reducing risk is key, Akella said, because “buyers are institutional investors, insurance companies, corporates, and various pension funds.” When the investment rating is high, they buy “in the hundreds of millions of dollars per year.”

The securitization transaction “goes through a lot of financial structuring and legal structuring whereby you are taking the risk of bankruptcy away from the transaction,” Akella explained, “And you are putting in what is called an over-collateralization (or credit enhancement) so that it is as high an investment-grade rating as possible on that bond.”

Securitization allows companies that own leases on solar systems to “shift assets on the balance sheet, sell into the capital markets in the form of bonds, which is debt, at a substantially lower cost of borrowing,” Akella said. “It is a means of borrowing at a cheaper rate than going to a traditional lending institution.”

The reduced cost of money for solar builders, Akella explained, could be passed to solar customers, making solar “even more affordable on a lease basis than it is today.”

Solar’s low risk profile is already attracting billions in institutional money.

As a result, end users are getting 15 percent to 20 percent utility bill cuts, installers have never been busier, institutions get the 30 percent federal investment tax credit (ITC) and the accelerated depreciation and share the lease payment cash flow with the solar companies until the tax equity is exhausted at the end of five or six years, when they sell to the solar companies.

The cash flow is guaranteed for another fourteen or fifteen years in the originating, twenty-year contract with the end user. By securitizing it and selling to an institutional investor, Akella said, the solar company can obtain lower cost money to initiate new solar deals.

The solar securities’ low risk hinges on the high certainty that end users will make their lease payments.

Utility bill payment is generally consistent because people value their electricity. And solar system users’ lease payments secure ever-improving value because, Akella pointed out, “utility rates keep going up. They have never gone down to my knowledge. They go up 2 percent to 3 percent annually on a national average.”

Also, he added, solar leasing companies have restricted themselves to end users with credit scores in the very high (680 and above) range.

With the increased and lower cost liquidity securitization offers, SolarCity spokesperson Jonathan Bass recently noted, it “is inevitable in solar [because] you have a cash flow that is more predictable than mortgage or car payments.”

The inevitable question is whether such asset backed securities could do the kind of harm to the solar industry that mortgage backed securities did to the housing market.

“Discipline is paramount,” Akella said. The housing market disaster was the result of over borrowing, inflated valuations and overleveraging. While many asset classes have been securitized, he added, “mortgages is the only place where things went sideways.”

“Don’t get fixated on the mortgage business,” Akella insisted. “Empirical data suggests that if we all -- within the supply chain and the ecology -- stay disciplined, this further financial innovation will help make solar technologies even more affordable for an average consumer because it will bring in investors who don’t have the wherewithal to look at solar directly but know securitized products.”

On the other hand, increased competition in solar is changing the third-party ownership industry. One CEO recently noted to GTM that he is looking for ways to make leases available to people with lower credit scores. Another CEO said he is seeing many more bad projects proposed than good ones. To use Akella’s terms, “discipline” in such a competitive solar “ecology” may not be “paramount.”