SolarEdge, the current market leader in residential solar module-level power electronics, also wants to be the market leader in battery-backed, energy-managed, grid responsive homes.

At this year’s Intersolar conference, it was showing off what has to compete against every other inverter maker in this early-stage, but very promising, new line of business.

So far, that includes “thousands of storage systems deployed in the market today,” said SolarEdge co-founder Lior Handelsman in a Wednesday interview at Intersolar. That’s largely driven by its early partnership with Tesla’s Powerwall, which has been deployed in the U.S., Australia and Europe since its May 2015 launch, he said.

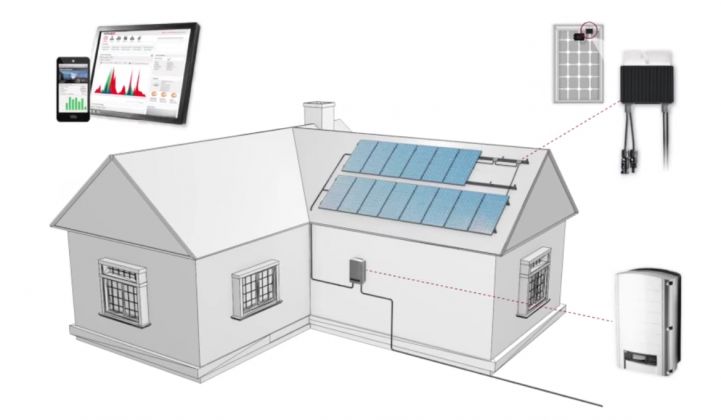

It also includes new battery partners such as LG Chem, its new StorEdge on-grid DC optimizer to manage solar and batteries as a single unit, and its recently launched suite of load-switching devices and water-heater controls, which brings household energy management into the mix, he said.

Like competitors such as Enphase, Tabuchi Electric, SMA and others, SolarEdge is also turning on the software-defined capabilities of its module-level power electronics, and tapping its fleet-scale, real-time data collection controls, to make the most of the batteries and loads it is connecting, according to Handelsman.

“Since the introduction of storage, we see much interest from utilities and network operators to provide grid services,” he said. “We are working with a few tens of utility companies globally on various demand-response types of projects,” ranging from a handful of homes in some cases to thousands in others, he said.

One such project, with Dutch utility Eneco, is demonstrating how aggregated fleets of inverter-controlled PV, batteries and loads can serve in primary reserves markets, he said. These are Europe’s equivalent to frequency regulation or ancillary services markets in the U.S., and can offer revenues to help cover the cost of batteries and load controls that can shift at the second-by-second reaction speeds required to help smooth grid imbalances.

Other projects are looking at creating virtual grid peakers out of aggregations of battery-backed solar homes that can store up energy to inject into the grid at times of peak demand, Handelsman said. Adding control over water heaters, pool pumps and other time-variable loads increases the flexibility of these homes.

Fully integrated projects like these are still in the pilot stage, he said. But self-storage of solar power is already economically feasible in some cases. “Australia, Germany, Hawaii -- these are major markets,” he said.

Finding additional grid values can also help cover the cost of installing batteries for emergency backup power, which is the main selling point for homeowners in most mainland U.S. markets, according to Handelsman. (That’s something that SolarEdge and Tesla are demonstrating with Green Mountain Power in Vermont, by the way.)

Of course, many other companies are staking their claim to serving as the master controller of solar PV, behind-the-meter batteries and home energy management combinations. Tesla and SolarCity have combined software for application in residential settings, and could get a lot more integrated if Tesla’s proposed acquisition goes through. Integrated systems from companies like Sonnen and Sunverge come with the same kinds of controls and features.

But “the inverter is the brains of the system,” said Handelsman. “It’s the connection to the grid, so the inverter needs to have the functionalities the system needs.”

As utilities, solar installers, energy services companies and other would-be integrators of these disparate systems start to mix and match different pieces of hardware to accomplish these goals, “the data management is the critical part, and usually the inverter maker does that.”

As more and more markets start to require “smart inverter” capabilities from solar installations, the role of inverter makers as utility interlocutor could be strengthened, he noted. Hawaii’s new solar regulatory regime requires inverters that can limit solar power feeding back to the grid, for instance, and its self-supply tariff is pushing solar installers like SolarCity to add smart thermostats and water heaters alongside batteries.

SolarEdge isn’t yet talking about the different business models it’s exploring to bring its capabilities to market. After all, “it’s not really a business yet,” Handelsman said.

“Is it something a company should hang its hopes on? No, because we don’t know when it’s going to be ready.” But when it is, “I have gigawatts installed globally, and I already know exactly what is going on with each system. Just add batteries -- there will be a business there.”