The tariffs that the Trump administration imposed on imported solar cells and modules in 2018 proved sufficient to boost some U.S. module manufacturing, according to a review by the U.S. International Trade Commission released late last week, but the duties did not have the same effect on U.S.-produced solar cells.

The review is the outcome of a midterm assessment of the tariffs’ impacts, which President Trump will use to determine whether to modify the duties that are currently set to disappear in 2022.

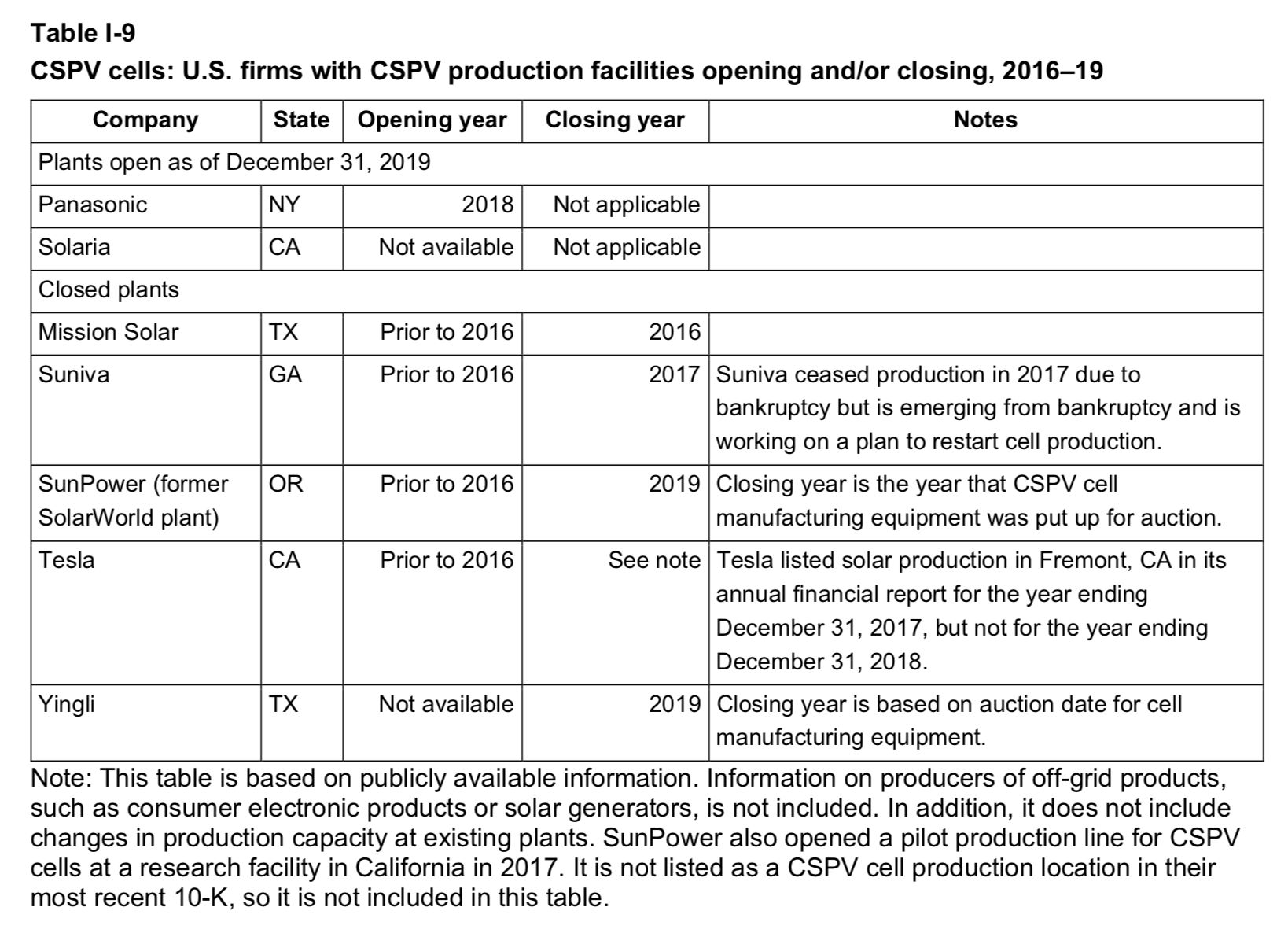

So far, the tariffs’ impact on the U.S. solar industry has been mixed. While foreign manufacturers such as Hanwha Q Cells, Jinko and LG set up module plants in the U.S. after the tariffs were imposed, thereby increasing manufacturing and jobs, the nation’s remaining cell plants continued to close; Panasonic and Tesla are now the only companies producing solar cells domestically. The tariffs also softened solar price declines in the U.S. compared to the steeper decreases seen globally, and an analysis from the Solar Energy Industries Association found that the U.S. forfeited 62,000 jobs, $19 billion in investment, and the environmental benefits that would have come from additional solar deployments.

The instigators of the tariffs, domestic cell and module producers Suniva and SolarWorld, haven’t bounced back. SolarWorld sold to SunPower in April 2018, and though the company continues to produce modules in the U.S., it has ceased cell production and lopped off its high-efficiency manufacturing arm to create a new company based in Singapore. Suniva exited bankruptcy in April last year, stopped producing modules and told the U.S. International Trade Commission it’s focusing on restarting cell manufacturing in the state of Georgia.

Source: U.S. International Trade Commission

With the compounding factors of additional tariffs on aluminum and steel — both of which are used in the manufacture of solar balance-of-systems equipment — and an exclusion for bifacial solar panels, untangling the impacts of the tariffs is a complex task. And the larger solar industry is far from unified over what should happen next. Some stakeholders suggest the tariffs need to be more stringent, while others, including Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA), are calling for their immediate dissolution.

It remains unclear when the president may act on the review.

Trading cells for modules

Encouraged by the guarantee of duty-free production, a wave of new and expanded U.S.-based module manufacturing facilities set up shop in the U.S. after the tariffs were announced, according to the U.S. International Trade Commission findings. Five module plants totaling 3 gigawatts of manufacturing capacity opened (although three U.S. module plants ceased operations during roughly the same period). The majority of these modules are shipped for use within the U.S.

Meanwhile, crystalline silicon photovoltaic (CSPV) product imports to the U.S. dropped by about 50 percent between 2016 and 2018. Products that China shipped to the U.S. fell from nearly 12 percent of China’s total shipments in 2016 to well under 1 percent in 2018 and the first few months of 2019. China was the largest source of solar products to the U.S. in 2016, but it has now been replaced by Korea and Malaysia.

Both Suniva and SunPower stopped U.S. cell production during that same timeframe. Although California-based Sunpreme announced plans in 2018 to open a 400-megawatt cell plant in Texas in 2019, the company hasn’t since announced any progress. All told, U.S. cell production dropped 75 percent between 2016 and 2018, according to the U.S. International Trade Commission. Cell imports jumped from 308 megawatts from January-June 2018 to 951 megawatts during that same period in 2019, an increase that coincided with the ramping of new domestic module manufacturing.

Due to what it terms a "significant" increase in U.S.-bound module manufacturing and a shortfall of domestic cell manufacturing, an industry coalition comprising SEIA and domestic manufacturers Hanwha, LG, Tesla and others is lobbying for an increase to the yearly 2.5-gigawatt quota the administration established for tariff-free cell imports.

“While the solar tariffs have resulted in some new U.S. manufacturing investments, total domestic cell and module capacity falls far short of demand,” said SEIA CEO Abigail Ross Hopper in a statement addressing the U.S. International Trade Commission’s review. “The tariffs have effectively constrained solar development in the United States.”

Commissioners on the U.S. International Trade Commission had recommended an even lower quota, at 1 gigawatt, ahead of the administration’s decision.

Another plea from Suniva

Section 201 petitioner Suniva, which was the first company to seek trade remedies before later being joined by SolarWorld, remains opposed to any increase in that cell quota. The company holds that the quota, plus the tariff exclusion for bifacial modules, has “delayed and diluted the remedial effect of the intended relief,” according to the U.S. ITC’s report.

Suniva wants the tariffs to be made more severe by slowing their stepdown, which is currently set as a 5 percent drop each year through 2021, and ending the bifacial exclusion. The company said tightening up the duties will allow U.S. cell manufacturing to benefit in the way that domestic module manufacturing has.

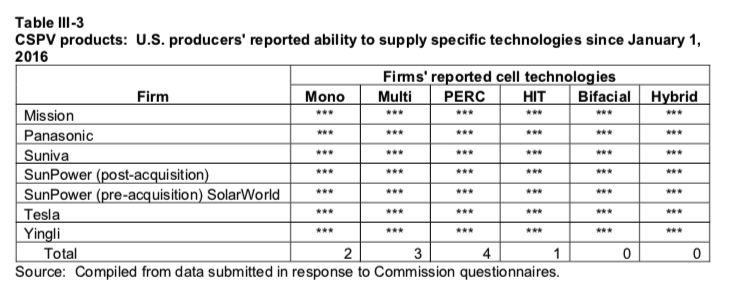

After exiting bankruptcy, Suniva — a company that was majority Chinese-owned when it filed the Section 201 petition but is now under U.S. ownership — is waiting for a $10 million cash infusion it said would help it restart solar cell production in Georgia. The company said it could resume production 100 days after securing that money. But with a capacity of 450 megawatts of monofacial PERC cells or 540 megawatts of bifacial PERC cells, production levels would not meet current domestic module demand, according to the analysis conducted by the U.S. ITC.

China’s solar boom

While the U.S. tariffs have restricted China’s access to the No. 2 global demand market, its own domestic solar industry has continued to flourish. In 2018, China accounted for 93 percent of global wafer production, 73 percent of global cell production and 72 percent of global module production — all substantial increases over its market share in 2010.

That growth is due in part to continued government support. Trina Solar, for instance, received $25 million in government grants to fund property, plant and equipment procurement between 2008 and 2010 and “unrestricted cash government subsidies” of $25 million between 2009 and 2015, the U.S. ITC said in its review.

Those incentives may be the outgrowth of China's unique philosophical approach to the solar industry. While the Trump administration has largely framed renewable energy technologies such as solar as a threat to coal and other legacy power sources, China has aggressively built out its solar supply chain. That’s a difference between market-based capitalism and state-based capitalism, said U.S. ITC Commissioner Jason E. Kearns, who was nominated successively by President Obama and President Trump, in the review.

“In recent years, the Chinese industry producing CSPV products, and upstream polysilicon and wafer products, has been provided with massive ongoing support at both the central and local government levels,” wrote Kearns. "This basic situation existed at the time of the original safeguard investigation and in all likelihood will persist beyond the four‐year period of safeguard relief."

Last year, 1366 Technologies, the only U.S.-based silicon wafer producer and a company incubated in the U.S. with Department of Energy funds, chose to join up with Hanwha Q Cells for its first large-scale production plant in Malaysia, while simultaneously working to secure a Section 201 exclusion.

“For China, addressing climate change means jobs,” wrote Kearns. “One has to wonder whether there would be greater support for efforts to address climate change in the United States if the U.S. had as many CSPV factories and jobs as China does.”

Boomerang bifacial solar policies

Next up for solar tariffs: The U.S. Trade Representative is gathering comments on the exclusion it granted for bifacial solar panels in June, then revoked in October, before a court ordered its reinstatement in December.

Though bifacial is still relatively marginal in terms of installation figures today, the two-sided modules are forecasted to make up one-third of global module production in 2022, according to IHS Markit.

The office of the U.S. Trade Representative says it's concerned that the exclusion will lead to significant imports of bifacial panels, undercutting “the objectives of the safeguard measure.”

Companies that invested in U.S. manufacturing in the wake of tariffs staunchly oppose the exclusion, which could eat into their economic advantage. It’s “effectively a loophole for Chinese-owned companies,” Hanwha, Mission Solar, Auxin Solar and SolarTech Universal argued in joint comments on the tariffs.

Source: U.S. International Trade Commission

The U.S. International Trade Commission notes in its review, however, that no U.S. producer has reported production of bifacial modules since 2016. SEIA called the exclusion “a fair and reasonable solution” to help loosen demand constraints. The trade organization expects 10 gigawatts of U.S. utility-scale demand this year, which current domestic supply is unable to match.

The U.S. Trade Representative is accepting comments on the potential to eliminate the exclusion, and responses to those comments, through February 27.