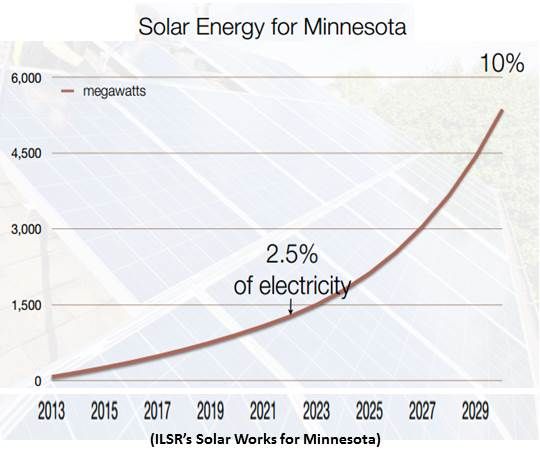

Minnesota’s solar resource is the same as that of Jacksonville, Florida or Houston, Texas, according to Institute for Local Self-Reliance (ILSR) Senior Researcher John Farrell. Its installed solar capacity is 13 megawatts. Farrell is part of a drive to have the legislature set a standard requiring 10 percent solar by 2030, which would grow installed capacity to some 5,300 megawatts.

“There would be a relatively modest ramp up to about 2.5 percent solar by 2022, accelerating up to 10 percent by 2030,” Farrell said.

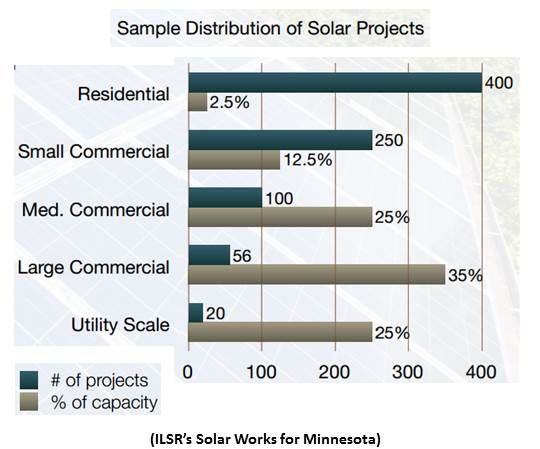

The 10 percent mandate, which would be the most ambitious in the U.S., would likely divide growth between residential (2.5 percent of new capacity), small commercial (12.5 percent of new capacity), large commercial (35 percent of new capacity) and utility-scale (25 percent of new capacity) installations.

To pay for the initiative, which is expected to be introduced in the legislature soon, Farrell wants lawmakers to institute a Value of Solar Tariff (VOST) as an option to the current net energy metering (NEM) and to legislate a production based incentive (PBI).

With a VOST, Farrell explained, “the utility makes a calculation that would be defined in the legislation about how much solar is worth to their system, because it is close to load, delivers during peak demand, avoids transmission charges, and so on. It would not replace net metering, but would be an alternative.” The twenty-year contract price, he said, should come out at “around $0.09 to $0.10 per kilowatt-hour.”

The PBI would also be a twenty-year contract, Farrell said, “and would be relative to the size of the solar array, bigger for residential solar and smaller for utility-scale solar.”

Minnesota’s installed cost for residential solar “is on par with the rest of the country at around $4.50 per watt,” Farrell said. “With the federal investment tax credit, the levelized cost of electricity is about $0.21 per kilowatt-hour. Our retail utility price is about $0.10 per kilowatt-hour.”

Farrell expects utilities to set the VOST at about the retail electricity price. It was calculated at about that by Austin Energy, its originator, and in subsequent calculations elsewhere. Because utilities want to get away from NEM “to solve a lot of their problems with fixed costs and cost recovery,” Farrell said, “the VOST price has to be pretty close to the residential retail rate people get through net metering, or it isn’t a viable alternative.”

The PBI, Farrell added, “stacks on top of the VOST and covers the difference between the VOST and the cost to install the system.” It will ratchet down over time, as growth drives economies of scale and lowers the installed cost. And to be prepared for when solar is more affordable, Farrell said, “we want to develop Minnesota-based installation and manufacturing.”

With a Democratic majority in both houses of the legislature and a solar-supporting Democratic Governor in Mark Dayton, Farrell said, the most controversial part of the initiative “is about Minnesota content requirements.”

The state’s approximately $4 per watt existing rebate, Farrell explained, provided extra support for systems incorporating modules made by Silicon Energy and tenKsolar, Minnesota’s two solar manufacturers.

Winning political support for the 10 percent by 2030 initiative, Farrell said, will require either a higher PBI or a set-aside for Minnesota-made modules. But the PBI might have to be $0.05 to $0.10 per kilowatt-hour higher and the set-aside might violate interstate commerce laws.

“There is a tradeoff between the overall price of the program and the focus on Minnesota content,” Farrell said. But the numbers justify the PBI that is $0.05 to $0.10 per kilowatt-hour higher. “The local jobs lead to additional economic impacts in direct and indirect dollars. The dollar in economic impact isn’t equal to the dollar in tax revenue, but we have an installed base of 13 megawatts and we’re talking about ramping up to 400 times that. It is going to help everybody.”

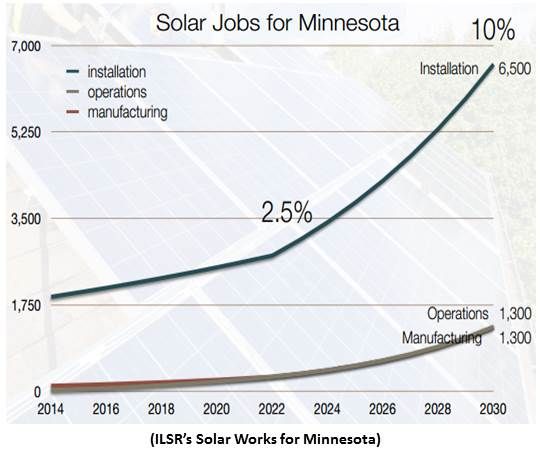

The initiative, Farrell found, would create 8,000 solar industry jobs, including 1,300 manufacturing jobs. It would also create $7 billion in economic activity and millions in electricity savings.

The incentives would cost Minnesota $37 million per year, or $1 per month per residential electricity customer. But January 2012 public opinion polling by the Minnesota Environmental Partnership showed that overwhelming majorities of Democrats, Republicans, and Independents in Minnesota support using more solar, and that 97 percent of Democrats, 86 percent of Independents and 89 percent of Republicans would be willing to pay at least $2 per month for it.

Governor Dayton is expected to introduce an alternative proposal soon. “Not everybody is on board with the 10 percent number,” Farrell said. “Rumor has it the Governor’s proposal might be in the 2 percent range, but by a much earlier date, like 2020 or 2022, which would make it similar in its short-term scope but without the big number at the end.”

There will be political pushback, Farrell said, “from folks stuck in the old paradigm who don’t understand how solar could ever be economic enough or reliable enough, and from legislators on both sides of the aisle who represent areas with rural electric co-ops and municipal utilities who believe solar will create a problem for them.”

But, Farrell said, “I am skeptical of such opposition, because the evidence is almost always that the benefits are greater than the costs and that there aren’t blackouts.”