This week, my colleague Varun Sivaram, Frank O’Sullivan I released a report through the MIT Energy Initiative on the past, present and future of cleantech venture capital.

As we wrote in an op-ed in the Financial Times:

In 2006, Silicon Valley began to bet big on clean energy technology. Seduced by grand visions of making a fortune while saving the planet, venture capitalists invested a then-record $123M in the first round of fundraising for 16 new companies that year. In 2008, they would sink nearly $1B in over 100 new companies.

But when these investments began to flop, the cleantech bubble abruptly popped. Since 2009, VCs have barely funded 25 new cleantech companies a year, slowing new investment to a trickle.

What went wrong? And where should cleantech go from here? To answer these questions, we compared the performance of every medical technology, software technology and cleantech company that received its first round of VC funding between 2006 and 2011. We found that betting on cleantech startups just did not make sense for VCs, because cleantech could not deliver the outsized returns found in other sectors.

This conclusion is alarming because new technologies are desperately needed to confront climate change. Still, guided by the lessons learnt from the cleantech VC boom and bust, new private and public funding sources may be able to better support revolutionary technologies.

Challenging the conventional wisdom: Cleantech just needs more money and more time

We hope that our findings will dispel the notion that the climate change can be solved by simply replacing VC money with patient capital. While it is true that the R&D needed to bring breakthrough innovations to market often takes decades and that building factories and manufacturing products requires substantial capital, there are further lessons to be learned from the first cleantech bubble.

What went wrong?

In short, investments in cleantech -- especially those in companies commercializing breakthrough energy technologies -- simply couldn’t deliver the outsized returns required by the venture capital model. We found five basic reasons that these companies failed:

- Long development cycles. Developing breakthrough materials, such as those for next-generation solar panels, can take 20 to 30 years.

- Significant capital requirements. To reach scale, venture capital money was used to build factories, in some cases before R&D was done.

- Business model failures. Many companies faced expensive customer acquisition and long sales cycles.

- No sales premium. Energy companies were selling into established commodity markets where price (of electricity or of the solar panel itself) was the main driver.

- Few exit opportunities. Acquirers in the utility and industrial sectors were not eager to take risks or place a premium on a startup’s growth.

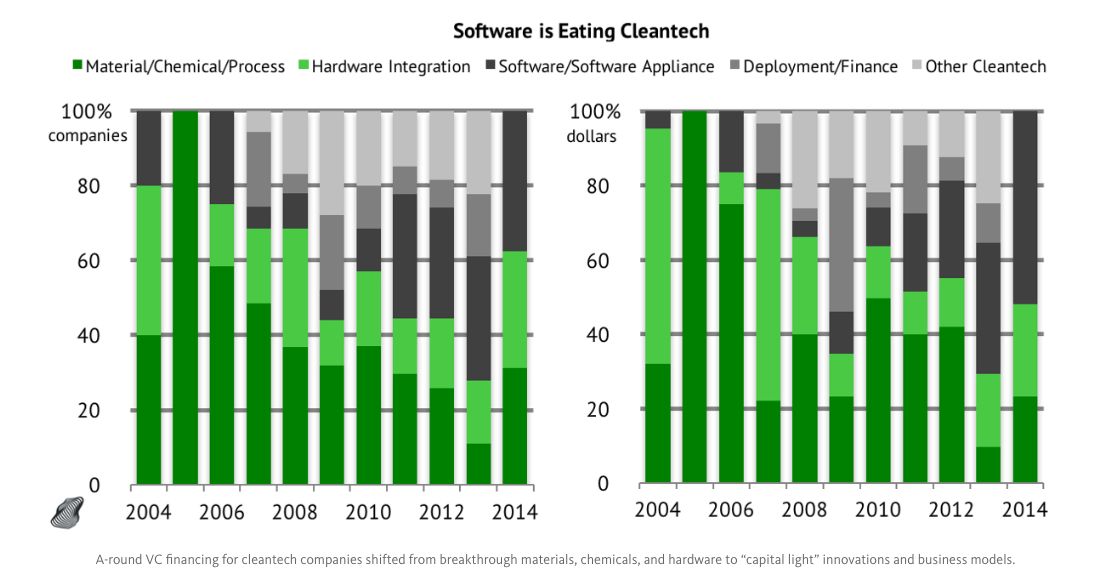

Software ate cleantech

The result was an overall retrenchment of venture capital in cleantech companies. Total funding for startups in the sector fell from $5 billion in 2008 to $2 billion in 2012. More importantly, funding for new companies took an even harder hit. In 2008, nearly 120 companies received their first major round of funding. In 2009, fewer than 30 companies could say the same -- a number that has remained approximately constant every year since.

What about the deals that are still getting done?

VCs all but stopped funding “deep technology” companies and shifted their focus largely toward software.

Who will fund the breakthroughs?

In order to avoid the worst effects of climate change through the year 2050 and beyond, we absolutely must both deploy as much existing technology as we can, as quickly as we can manage, and with clever new business models -- but the magnitude of the problem will require new breakthroughs. There has been a substantial evolution of the ecosystem since the boom and bust, but the battle is not won yet.

First, public-sector support of energy R&D has been buoyed by ARPA-E, the Department of Energy’s advanced research projects arm. More recently, in committing to Mission Innovation at the Paris climate talks last year, President Obama pledged to double the nation’s energy R&D budget over the next several years. Other commercialization and technology transfer efforts within the Department of Energy have provided increased access to our National Laboratories and infused an entrepreneurial culture inside the Lab system. In just the past few years, DOE has launched Cyclotron Road and Chain Reaction Innovations, Small Business Vouchers, and LabCorps, and has established the new Office of Technology Transitions.

New sources of capital are also available. A number of foundations, family wealth management offices, and high-net-worth individuals have begun pledging to support these breakthrough technologies. Keep in mind that these are largely not new actors: these investors were the source of capital originally deployed by the VCs in the first wave of cleantech. Now, however, some feel that by investing directly or through syndicates, they may avoid the short-term horizon imposed by the typical venture structure.

Last fall, Bill Gates and 27 other billionaires announced the Breakthrough Energy Coalition, pledging to put billions of dollars to work over the long term to support emerging technologies. Meanwhile, the Prime coalition is helping foundations and philanthropists invest directly in game-changing technology companies, often before other institutional investors would be willing to take such risks.

But capital is only part of the equation. Cleantech companies require much of the same support as other types startups: help with developing sales strategies, hiring the right key employees, marketing and fundraising. But they also require some things a SaaS company doesn’t: lab space, manufacturing expertise, and -- particularly important when selling to risk-averse adopters -- opportunities to test and demonstrate their technology.

In the decade since the cleantech boom started, a number of incubators and accelerators have stepped in to fill these gaps. My organization, Clean Energy Trust, invests in and works directly with startups to help them through this early scale-up process. Others, such as the Los Angeles Cleantech Incubator and Greentown Labs in Somerville, Massachusetts, provide physical incubation space for new companies. Cleantech companies now have improved access to first-of-a-kind demonstration and pilot projects through programs like the Wells Fargo/NREL Innovation Incubator, the Energy Excelerator demonstration track, and CET’s Campus Cleantech Pilots. Large industrial corporations and utilities are also increasingly becoming aware of the need to work with innovative companies. For example, through our Cleantech Innovation Bridge, we match startups with corporate partners in need of emerging technologies.

No exit: Funding the slow-growth company

There is no doubt that the support structures for new emerging technology companies have gotten stronger, and we hope that this will fuel increased interest in solving climate change through innovation. Before 2012, some cleantech companies were able to raise over $500 million in venture capital before turning a profit. That is simply not likely to happen again.

The model for success in the current funding environment has not yet been proven, though there are a few predictions we can make. To succeed, cleantech founders will have to run lean. First, they will have to take advantage of incubators and accelerators and will need to fund R&D through public grant funding. Later, they will need to rely on debt for projects (such as Black Coral and Generate Capital) and manufacturing (including private working capital revolving funds and public sources such as OPIC) as an alternative to equity financing. Throughout the process, cleantech founders should be in close contact with corporate and strategic partners who will be not only the likely customer for the product, but also potential acquirers of the company.

Finally, cleantech companies will need to build a business on the assumption that they will be valued based on their profits, not their growth.

Closing thoughts

Venture capital didn’t work for cleantech because there were better places to invest. But that doesn’t mean it’s not a sector worth investing in. As many others have put it: climate change is the greatest challenge we have faced in a generation, and the transition to a low-carbon energy system will be the single greatest economic opportunity in our lifetimes.

***

Ben Gaddy is director of technology development at Clean Energy Trust in Chicago. Ben works with small early-stage companies to help bring their technology to market. This piece was originally published at Medium and was reprinted with permission.