If thin-film solar companies such as Nanosolar, Miasole and SoloPower succeed, a new company called SMG Indium Resources Ltd. could also benefit.

The reason for which is indium. Those companies plan to make solar panels that use the metal, which is only produced in small amounts today.

SMG – which this month filed an IPO to raise $55 million on the American Stock Exchange – plans to use the money it raises to stockpile indium in the hope of selling it for higher prices in the future.

The company plans to sell 11 million shares at an initial price of $5 each, netting $51.3 million after expenses of around $3.7 million. Additional underwriters' overallotment options could bring the total as high as $59 million, and the aggregate offering could reach a maximum of $145.8 million once all the warrants and options are included.

Nathaniel Bullard, a senior analyst at research firm New Energy Finance's Washington. D.C. office, called the fund "quite interesting."

"I'm curious to see this happening," he said. "There's likely to be a fair amount of peakiness in the price for indium as the [CIGS] solar market increases against a backdrop of steady demand from other sectors, such as the LCD and LED markets. There's probably a built-in demand from that [LCD] market regardless of what happens in the CIGS market."

Indium prices haven't been a concern so far, as the market for the metal – which today is produced only as a byproduct of mining for other metals, mainly zinc – has remained small.

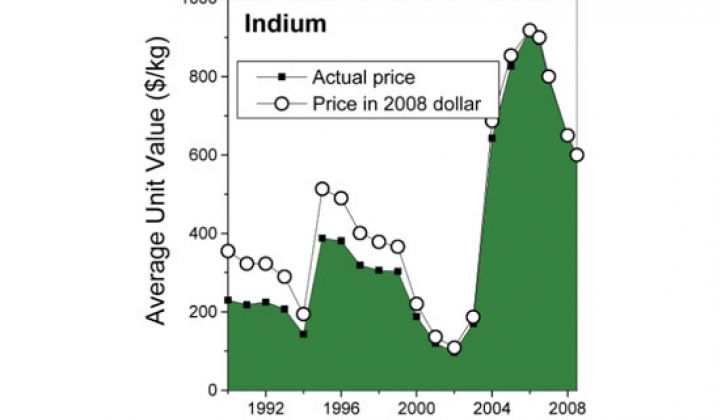

In fact, prices have fallen "substantially" since 2005, reaching $500 per kilogram on Sept. 2, according to the prospectus filed Sept. 5.

SMG estimates that the total worldwide indium market reached approximately $709 million in 2006, based on demand and price figures from DisplayBank and Metal Bulletin. DisplayBank projects that total sales shrunk to $533 million in 2008, in spite of an increase in demand to 1,000 tons from 861 tons in 2006.

But SMG believes the trend will reverse course. After all, the price of indium has grown over the longer term.

"It is our belief that the long-term industry prospects for indium are attractive and over time the price of the metal will appreciate," according to the prospectus.

Part of the reason for this appreciation is that the current indium markets da s h; most notably displays, including flat-panel and liquid-crystal displays – are on the rise. Indium also is used for LEDs, as well as other electrical components, alloys and solders.

For the greentech industry, perhaps the most exciting indium market is thin-film solar, specifically copper-indium-gallium-diselenide films also known as CIGS.

Companies developing such films claim they could convert sunlight into electricity more efficiently than other films, but none have yet reached significant volumes, analysts say.

Still, as Wall Street darling First Solar (NSDQ: FSLR) has raked in cash, contracts and company value for its cadmium-telluride films, which cost less per watt than traditional crystalline-silicon panels, investors and industry insiders are looking to CIGS as a possible competitor.

Several CIGS companies have raised eyebrow-raising rounds in the last year and also have announced steps toward commercialization.

The most recent was SoloPower, which raised $200 million, VentureWire reported last week (also see Green Light post).

Nanosolar in August confirmed it had closed a $300 million equity round, after announcing it had begun production – although declining to disclose the extent of its production – in December (see Nanosolar Confirms $300M Funding and Nanosolar Begins Production).

In July, Global Solar Energy also said it had begun production and sales (see Global Solar Sells Out Year's Production, Global Solar Strings Thin-Film Market Together, Q&A: Solar Solar VPs Dish Thin-Film Details and Competition for First Solar?).

HelioVolt Corp., which is planning a ribbon cutting to celebrate the opening of its first factory on Oct. 24, announced last October that it had raised $101 million (see HelioVolt Gets More Cash for Thin Solar and HelioVolt on Nanosolar's Heels).

And according to Greentech Media's Green Light blog, Miasole, which in May said that it plans to ship its first commercial panels to customers by the end of the year, is raising cash, as well as Solyndra Inc. (see Green Light post here and here).

If CIGS production grows as these companies hope, indium production might not be able to grow alongside it, especially if the market for LCDs also remains strong.

While indium is about three times more abundant than silver or mercury, according to the prospectus, the available amount is much less.

Because indium naturally occurs in small amounts mixed with other metals, it doesn’t make sense to mine for indium alone, according to the SMG prospectus.

Indium is found mainly in sphalerite, a zinc-sulphide ore mineral, and is mostly produced as a byproduct of zinc ore processing, although it’s also found in iron, lead and copper ores, the prospectus stated. The element usually makes up between 1 part per million and100 parts per million of the zinc deposits in which it’s found, it said.

Materials shortages are not a new concept to the solar industry, which is still recovering from a shortage of silicon – the key material in traditional crystalline-silicon panels.

Companies developing thin-film solar, which uses little or no silicon, have cropped up partly to help solve that problem. But that doesn’t mean they are immune to other shortages.

Some industry insiders have questioned whether First Solar, the No. 1 thin-film solar manufacturer, will one day run out of tellurium for its cadmium-telluride films, for example. Tellurium, the rarest of the metals used in thin films, is as scarce as gold, according to Alex Freundlich, head of the photovoltaic and nanostructures laboratories at the University of Houston’s Center for Advanced Materials, in a presentation in July.

First Solar claims it has secured enough of the material to avoid a shortage anytime soon, and uses so little of it – about 6 grams per square meter – that it can afford to pay top dollar, said Freundlich, who also is a professor of physics and electrical and computer engineering at the university.

Still, the average price has grown from less than $100 per kilogram from 1992 through 2004 to between $250 and $270 per kilogram so far this year, he said, citing data from the U.S. Geological Survey.

5N Plus, a Quebec-based company that supplies tellurium to First Solar, has benefited from the growing prices (see Clean Break post). In August, the company reported a net income that more than doubled to C$7.7 million for the fiscal year, which ended in May.

SMG hopes indium will be the next tellurium, and Bullard said the scenario is possible.

"I can see the play along the lines of tellurium," he said. "It’s a relatively rare metal and it’s also produced primarily as a byproduct of another metal refining process, so there’s no primary process for producing indium."

SMG, founded as Specialty Metals Group Indium Corp. in January, in July signed a deal with Unionmet Ltd. to buy a minimum of 10 metric tons of indium within 10 months of the offering.

The price will be set by an undisclosed formula that both companies have agreed upon, according to SMG, which added that it doesn’t intend to rely mainly on Unionmet for its indium supply.

The company has flown under the radar, probably because it hasn’t had any significant operations so far. According to its prospectus, SMG - which hasn’t incurred any costs or accumulated profits yet - has $50,936 of cash on hand, with $258,779 in assets and no funds available for buying indium.

According to SMG, investors are unable to trade on indium prices unless they buy and physically take delivery of the metal today, according to the prospectus. Indium futures aren’t traded on the commodities markets, for example. The company hopes to fill that gap.

It intends to spend 85 percent of its net proceeds from the IPO – about $43.6 million – to buy indium and the remaining 15 percent – about $7.7 million for general corporate purposes, including working capital.

SMG plans to store the indium in third-party warehouses in the United States, Canada or the United Kingdom and to "use its best effort" to fully insure the stockpile. It also plans to pay its manager a 2 percent annual fee based on the company’s net market value.

The company expects its annual expenses to total about $1.67 million and expects the IPO should bring it enough case to operate for 48 to 55 months.

To offset its costs and retain its net market value, the price of indium would need to increase approximately 12.4 percent within the first year, 16.2 percent within two years - an average of 8.1 percent per year - and 20.1 percent within three years, or an average of 6.7 percent per year, according to SMG’s prospectus.

The company faces plenty of other risks as well.

First of all, it is depending on an unproven business model and a new market that might not grow as quickly as predicted.

According to Freundlich, CIGS solar equipment needs about 30 tons of indium per gigawatt of capacity, or about 3 grams per square meter of CIGS cells.

In a Greentech Media and Prometheus Institute report released earlier this month, analysts predicted that 2009 will be "a breakout year" for many CIGS companies and forecast that production will grow from 27 megawatts in 2007 to an estimated 142 megawatts in 2008, 912 megawatts in 2010 and a whopping 3.09 gigawatts (3,088 megawatts) in 2012, when the technology will make up nearly a third of the projected 9.61-gigawatt thin-film market (see Thin-Film Solar Set to Take Market Share from Crystalline Solar PV).

Three gigawatts of capacity would require about 90 tons of indium, according to Freundlich’s equation. That seems supportable given that world production reached about 550 metric tons in 2006 and 500 metric tons in 2007, according to the USGS, but could amount to a shortage if other markets grow at the same time.

And of course, if CIGS doesn’t do as well as expected – or is replaced by new technology - while other markets also slow, the demand for indium could decrease.

Also, because the company doesn’t plan to test the purity of the indium it buys - although it does plan to use only reliable suppliers – it could end up buying indium that is less pure than the 99.97 percent purity it requires, meaning the indium would be worth less than expected.

And the executives and directors are employed elsewhere and are not required to work full-time at SMG, which could create conflicts of interest, according to the prospectus.

But the risk that caught at least one analysts’ attention is the following:

"Our officers and directors have no experience in purchasing, stockpiling, selling, storing and lending indium and our officers and directors have limited experience in purchasing, stockpiling, selling, storing and lending minor metals."

Bullard said he isn’t sure how much of a disadvantage that lack of experience might turn out to be, if any. Apparently SMG doesn’t think it needs any specific knowhow to succeed.

But if it does, it could bring out the copycats. "Anyone with the cash on hand and particular bullishness on this metal could go ahead and do it," Bullard said.

A company already in the industry, such as a zinc smelter or a firm that trades in rare metals, could well have an advantage if it decides to compete with SMG, he said.

Perhaps SMG can win itself a first-mover advantage if it’s able to buy up enough indium quickly.