Property taxes can be an ongoing cost for PV system owners and a determining factor in whether a solar system gets installed.

“That makes planning for the property tax burden challenging in perhaps 25 percent to 50 percent of situations and it is especially hard in cases where there are novel applications like third-party ownership,” explained Justin Barnes, a Keyes, Fox & Wiedman Senior Policy Analyst and the lead author of the DOE Solar Outreach Partnership’s report Property Taxes and Solar PV Systems: Policies, Practices, and Issues.

Where there is no specific policy in place, the system is likely to be assessed according to whatever the local standard practice is. “Assessments get made on a case-by-case basis,” Barnes said. “In Connecticut, for instance, residential systems are exempt, and sometimes assessors choose to include commercial and industrial systems, and sometimes, probably in detriment to the finances of the project, they don’t.”

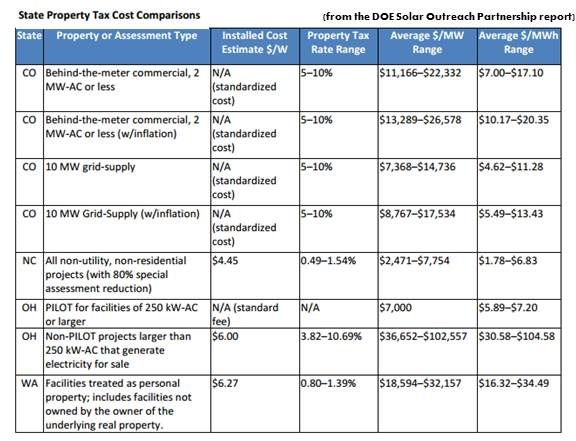

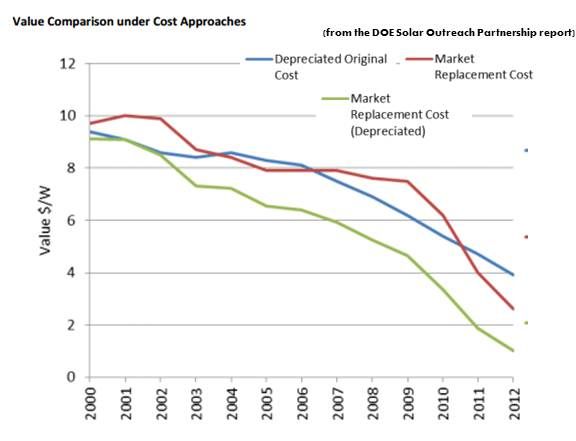

Barnes said there are three generally accepted property tax valuation methods used by assessors: the comparable sales method widely used in residential real estate, the cost-based method in which a replacement cost is estimated, and the income method.

“In residential settings, it is difficult to use comparable sales because there aren’t a lot of good ‘comps,’ and the income-based and cost-based methods are not typically factors in residential assessments,” Barnes said. “In many cases, an assessor will just ignore the PV system, essentially assigning it no value, because there is no established assessment method.”

Some states require assessors to consider all three methods to determine a “reasonable” value. Some have the assessor choose the method for which the most data is available. “For commercial and industrial systems, income-based and cost-based methods are more familiar,” Barnes said, “but the market is changing so fast that the estimates can be very inaccurate.”

Most assessors say there is no good generalization that can be used to replace their customary standards and practices, especially for calculating something so subjective and complicated, Barnes explained, but without guidelines and rules, there is no certainty about the system’s projected tax burden.

“Disputes between property owners and local assessors over all kinds of things are common,” Barnes said.

“Property tax issues don’t affect the value proposition of third-party ownership, but they figure in on what the property owner owes on taxes,” Barnes explained. “The assessment will affect what the third party owes to property taxes, and that filters down to what the customer pays in a lease or PPA rate.”

Tax returns can be cross-checked to clarify property tax responsibilities, Barnes said, but most assessors interviewed for the paper “had very little understanding that third-party ownership was even a possibility and would simply assume the property owner was the system owner.”

Barnes discovered a several states where tax assessments have impeded solar market growth. Laws have recently been altered in Texas, Vermont, and Ohio to clarify issues.

“Massachusetts has been a nightmare," he said. The state has an exemption for systems that provide energy for on-site use. But it also has virtual net metering (VNM), and it can pass net metering credits to different accounts and customers. When the credits are passed to a meter at a different location, it raises the question of whether that energy is being used on-site.”

In the same way, basic net metering has raised questions, Barnes said. “The electricity that is not used goes back to the grid. It is not used on-site. It can therefore be taxable. That is a narrow interpretation but it has happened.”

Colorado may have the most exemplary property tax system, Barnes said, and Ohio’s is noteworthy for its simplicity: “Systems below 250 kilowatts are exempt and those above 250 kilowatts pay a set fee. Simple. Easy.”

Because “PV is destined to increase over time, and dramatically so,” the paper concluded with six suggestions toward best practices:

- Property tax laws should apply to the specific state’s PV market

- State and local jurisdictions should record the data needed to determine PV system value

- Tax policy should specify whether PV systems are real or personal property

- Policies should clarify how cost-based and income-based valuation methods should be applied

- Because PV systems have high upfront costs but are fuel-cost-free, alternate valuations like capitalized income or a dollars-per-megawatt fee might be better approaches

- Income-based and comparable sales methods could supplement income-based valuation

The most important elements, the paper stressed, are “clarity, permanence, and predictability.”