It was when John Paul Morgan was living in Congo, where he managed logistics for medical nonprofit Doctors Without Borders, that he was struck by the true importance of electricity.

A nearby town was plagued by cholera outbreaks because of frequent electrical outages that kept the water pump from working. The town he lived in, Shabunda, wasn't electrified at all; near the equator, that means no reading, no schoolwork, no housework – just utter darkness after the sun sets around 6 p.m.

"My friends are all desperate for electricity," he said. "The ability to see where you are and what you're doing is something we take for granted, because we can always control our environment. Not having power over your environment is ... debilitating and it influences the control you have over other parts of your life as well. When you're sitting around in the dark, you're sitting in the dark; you're kind of lost."

He became convinced that electricity was essential to education and to moving towns like Shabunda beyond subsistence farming, and he came home frustrated because he didn't think they would get out of what he calls "the dark ages" anytime soon.

So Morgan set his mind to solving the problem. He holed up in his living room for several months and emerged with what he says is a completely new type of solar panel that could dramatically reduce the price of solar power.

Backed by investment from their father, Eric Morgan, head of Capgemini in Spain, Portugal and Latin America, John Paul and his brother, Nicolas, launched stealthy Toronto-based Morgan Solar in June of last year. John Paul is the chief technology officer and Nicolas is the director of business development.

They have grown the company to seven people and raised a total of $1.5 million, with about half in cash and half in noncash contributions. Of that amount, approximately $1 million came from the Morgan family and $500,000 came from government grants and other sources, including the National Resource Council's Industrial Research Assistance Program.

Toronto-based Morgan Solar plans to install a 1-meter-by-1-meter (3.28-foot-by-3.28-foot) prototype panel on an aviary at the Earth Rangers Centre in Toronto and begin producing electricity from the panel by the end of September. The center, founded by Robert Schad – who previously founded Husky Injection Molding Systems, which sold to Onex Systems for $960 million last year – will independently monitor the trial panel.

Morgan Solar plans to install another eight panels on the center in October, and also is talking with potential partners in Spain who are considering testing Morgan's concentrators for 1 megawatt of projects, Nicolas said.

And the company has ambitious plans beyond the demonstration stage. Morgan Solar is working to raise an additional $10 million to $20 million and reach mass production in about a year.

"Six months ago, we were a company with an idea," Nicolas said. "Six months later, we're going to be a validated company with a reputable product."

The Technology

That product Morgan Solar is developing involves a thin sheet of acrylic that concentrates sunlight 750 times and redirects it to a tiny multilayered cell on the edge of the plastic, reducing the amount of photovoltaic material needed to convert sunlight into electricity, according to the company.

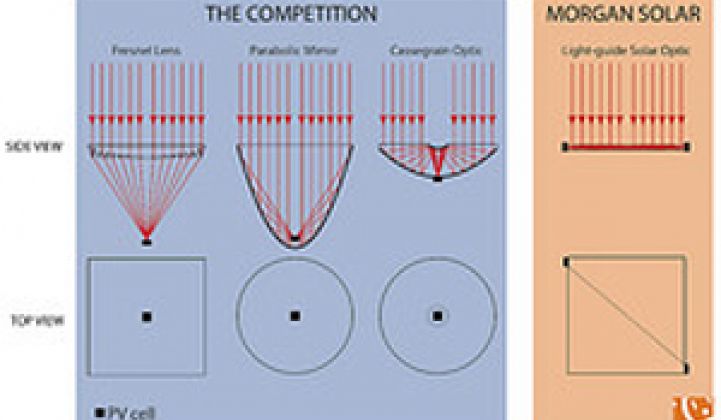

Other companies, such as SolFocus, Concentrix Solar, GreenVolts and Sunrgi, have for years been working on solar concentrators, which attempt to make solar power cheaper by using mirrors or lenses to magnify sunlight and direct it into a solar cell, which converts it into electricity. The idea is that being able to guide more light to a smaller solar cell would use less of the photovoltaic material – usually the most expensive material in a panel.

But concentrating-solar companies face several challenges.

For one thing, directing sunlight into one place can cause some panels to overheat and break down. The heat can also cause different materials in the concentrators to expand at different rates, leading to wear and tear.

Morgan Solar believes it has solved those problems with its new technology, which concentrates sunlight using what it calls a "light-guided solar optic" instead of a lens or reflector to direct light to the cell.

Two triangular optics are put together in a package about the size and shape of a CD case, each drawing light to one corner of the concentrator, Nicolas said. A panel will consist of 80 to 100 of these CD-case-like arrangements, he said.

The company says the design is cheaper, uses less material and is less likely to break than its competitors' systems.

By guiding light to the edge – not the bottom – of a panel, the concentrator releases heat instead of trapping it and doesn't overheat, according to Nicolas. He said thermal-modeling software has projected that the hottest part of the concentrator will reach a maximum of 86 degrees Celsius (186.8 degrees Fahrenheit), which he claims is a fifth of the heat of comparable systems, in the hottest conditions on Earth – 50 degrees Celsius, with zero wind, zero humidity, and maximum sunlight.

The concentrator is made of a single piece of plastic, avoiding thermal-expansion problems, Nicolas said.

The system also is less likely to break because its shape exposes it to less wind pressure than other systems, which have to be built to withstand the wind, he said. Combined with the low weight from the thin piece of plastic, the ability to withstand a higher wind load translates into cost savings on the tracker, which moves the panels alongside the sun, he said.

But the main advantage, according to Nicolas, is the potentially lower cost. Morgan Solar claims its technology could reduce costs to a quarter of its concentrating-solar competitors' costs with a design that uses much less in the way of materials – just a little bit of aluminum, acrylic and PV – and that it expects will be easy to manufacture.

"We've reinvented CPV. Now it's affordable," the Website boasts.

At that cost, four times cheaper than it is today, solar would be within reach of people John Paul knew in Shabunda, he said. That would mean that a 50-watt panel, which would be enough for a family to run two very efficient light bulbs in the evenings, would cost $100 instead of $400, he said, which his friends could borrow or otherwise finance.

"Obviously, the cheaper the better," he said. "But when I think about what would be the threshold to be able to get wider adoption spread where I was in the developing world, four times cheaper would make a big difference."

Morgan Solar hopes its technology will help make solar farms cost-effective, without any subsidies, sooner than the industry expects.

"The real goal is to be able to build solar panels that cost less than electricity can be produced today, and I think we can do that in the next year or two," Nicolas said. "We're not going to be the one company that makes solar affordable, but we're going to be one of the companies pushing the industry to be cheaper faster."

Other concentrating-solar companies already have seen some success.

SolFocus in July said it had completed the first phase of its first project (see SolFocus Installs Concentrating-Solar Project in Spain). Concentrix Solar said earlier this month it plans to begin production of its new generation of panels in September (see Solar Roundup: Earnings, Expectations and Updates).

And the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in July said it was spinning out a startup called Covalent Solar to develop technology that uses organic dyes to concentrate solar (see Dyeing for More Solar Power).

Nicolas said Morgan Solar's technology often is compared to the MIT technology, but claims that the company's optics can draw light to a more specific point and are more efficient.

Challenges Ahead

But the company still has some unanswered questions, and hopes the test will help answer them.

For one thing, it isn't sure how much electricity its panels will deliver or what their efficiency will be, although Nicolas said it expects its efficiency to be at least comparable to other concentrating-solar panels of equal size.

Another uncertainty is the exact material it will use to make its concentrators.

Morgan Solar hopes to use acrylic, which it believes will fit the requirements of its technology and cost 3 to 5 percent less to work with than glass, which is most commonly used for panels today.

But nobody has ever put that much light through acrylic before, according to Nicolas, and while scientists are "pretty sure" the material will work as expected, the company won't know for sure how it will react until it is tested. Nicolas said that if the material doesn't handle the light as expected, the company plans to switch to another one, such as glass.

The company plans to share more details about its technology later this month after it finishes submitting its patents.

Jed Dorsheimer, an analyst at Canaccord Adams, said while the technology apparently works in the laboratory and makes "a lot of sense" in theory, Morgan Solar's challenge will be to actually commercialize the technology.

All new solar technologies face the commercialization challenge, and concentrating PV companies also face the hurdle of demonstrating reliability so that banks will finance the projects, he said.

He added that while lower costs certainly would position Morgan Solar favorably, cost has not been a major impediment to concentrating PV, also called CPV.

"I don't think cost is the big issue for SolFocus, GreenVolts, Concentrix or Emcore," he said. "The biggest challenge is making sure the statistics are actually there and that companies can demonstrate them and get banks comfortable that CPV is not just some science project."

Meanwhile, Neal Dikeman, a founding partner of Jane Capital Partners, warned that concentrating-solar technology has a tiny market share today – less than 1 percent of the solar market - and could remain small if silicon prices shrink.

"I think people investing are investing in [CPV companies] because people couldn't get silicon," he said. "But if the cost curves continue to fall in silicon, why do you need concentrating?"

He said it will be too early to tell if the technology will work at larger scale even after the company completes its first test at the Earth Rangers Centre. "Tell them to call me after their 10th test."

But he added that the idea does have potential. "If there is one that works, something solid state [like Morgan Solar's concentrator] would probably be it."

The question is whether the company can get products on the market before others, he said.

The Race to the Finish

John Paul agreed the company is in a race.

"There are other people who are saying they're going to do the same thing or are trying to do the same thing," he said. "I think we're going to be much cheaper than other techs on the market."

Nicolas said all the startups working toward the same basic objective of low-cost solar power are good for the industry.

"There are seven or eight other companies just in Ontario that are going to come out of nowhere and surprise everyone," he said. "Maybe one in 10 really [deliver on their] announcements, but there are going to be thousands of announcements; it's going to be a really exciting thing for solar."

Morgan Solar expects to target industrial and commercial customers with its first concentrator products, aimed at projects in the 500-kilowatt to 1-megawatt range, Nicolas said.

Assuming it raises the $10 million to $20 million round it is seeking, Morgan Solar hopes to enter mass production between June and August of next year with its production panels, which will be larger than the demonstration panels at about 1.5 meters by 1 meter (about 4.9 feet by 3.28 feet), he said.

After the release of its first product, the company plans to increase the magnification power of its concentrator and believes it can reach as much as 1,400 suns - 1,400 times natural sunlight – using current multilayered cells.

Morgan Solar also has plans to develop two other products for buildings: a window that it expects will concentrate sunlight fourfold and a solar wall intended to concentrate sunlight between six- and eightfold, Nicolas said.

The company expects to begin working on these lower-concentration, building-integrated products in October or November and to bring them to market at around the same time as its first product, he said.

But it's focused on its higher-concentration product for now.

Based on groups it already has spoken with, if the technology works as planned and can be made as cheaply as expected, Morgan Solar already will be sold out for next year, Nicolas said. "We already have fairly advanced conversations with people about producing products, which is both scary and awesome."

The company aims to start its commercial rollout of its first product in North America and Europe – specifically Canada, the United States, Spain, Portugal, Germany, Italy and France – and later hopes to also sell in Asia.

None of these first markets are developing countries, and John Paul said to make no mistake – he's essentially a capitalist. It makes sense to target markets that will pay the most first.

Still, he said, his ultimate goal remains to make a difference in places like the Congo.

"Once you can make the systems inexpensive, then those third-world markets will start to be able to gain access to these systems and it will be deployed on a wider scale," he said. "That's where I want to take this – really widely avail power for everyone and not merely for Spain and Germany and the hot solar markets right now."