Earlier this summer, NV Energy told solar installers that a 235-megawatt limit on net-metered solar would be met by the end of July. The limit was meant to last through at least the end of the year -- but new solar installations have already come to a halt in Nevada.

If Nevada had standard net-metering reporting requirements in place, some of the confusion could have been avoided.

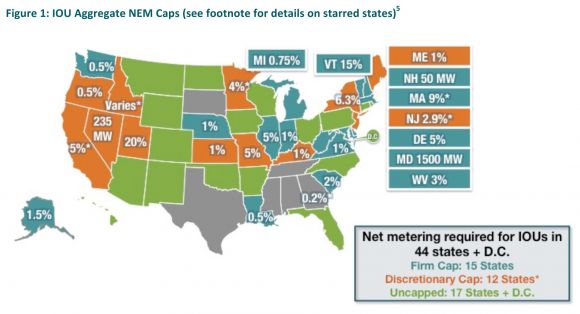

Confusion over net-metering caps -- and more importantly, how close states are to hitting them -- is rampant, according to a new white paper by EQ Research. Somewhat unsurprisingly, the report concluded that consistent, transparent reporting is necessary for a healthy solar market, while poor data-reporting practices destabilize the marketplace.

“Understanding the future availability of net metering in a state is critical to project planning and decision-making for solar developers, customers and policymakers,” Justin Barnes, director of research at EQ and lead author of the study, said in a statement.

Without thorough and accessible data, measuring the availability of net metering is “an unpleasant guessing game.” For the many states with caps, “These caps have traditionally been set arbitrarily and incrementally -- arrived at via negotiation rather than through principled analysis -- and their impact on each state’s long-term DG market is profound,” wrote analysts from EQ.

Reporting on net-metering caps varies widely between states. Some have to report on whether the cap has been hit, but many do not. Because accurate figures on utility peak load often are not shared with third parties, it can be difficult for outsiders to calculate how close the caps are to being met.

The study recommends a few data points that should be common across utilities and states:

- First, reports should specify the aggregate net-metering cap in megawatts, rather than some other measure.

- As utilities get closer to reaching caps, notifications should be sent to regulators to consider if a change of policy is needed before the cap is actually hit.

- Reporting on the number of net-metered systems is not enough. Instead, reports should include aggregate capacity of all active and pending systems.

As with most reporting, data lag and frequency also play significant roles. For most states, the data lag is two to three months. Massachusetts is the clear outlier, with a dedicated state website featuring real-time data.

Overall, Massachusetts was the leader in terms of frequency and types of data provided, while Virginia and Illinois were noted for having the worst practices. The study acknowledges that net metering is often seen as a temporary fix in states, and therefore robust reporting practices were often not established when the policies were put in place.

But for states looking to move beyond net metering, consistent reporting and granular data will become increasingly important.

“Good, reasoned, and well-supported decision-making on such an important issue takes time, or at least it should,” Barnes concludes, “and creating a reasonable opportunity for this to occur by improving net-metering reporting requirements is not particularly difficult.”