When a company introduces a new product that enjoys rapid uptake and changes the way an industry works, that generally coincides with a positive business outlook.

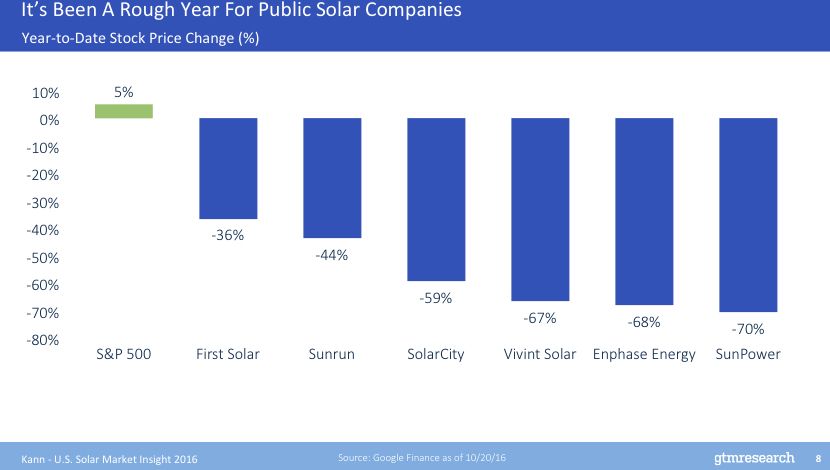

But these are strange times in the clean energy world, when the nation's biggest solar installers are performing, well, unenergetically in the stock market. Unprecedented deployments coincide with a slowdown in the growth of residential solar even as prices continue to fall, and the big players in the industry are scrambling to cut their costs in order to keep up. That tumult crosses over into an auxiliary industry: inverters.

One of the more exciting developments in the inverter world is the trend toward the small -- moving from big centralized inverters serving a group of solar modules to power electronics being located on each module individually. Enphase, now in its tenth year of existence, leads the market for microinverters that do just that, while the younger SolarEdge offers a competing technology that puts DC power optimizers on each module and connects them to a string inverter.

These two companies together controlled 95 percent of the module-level power electronics market in 2015.

Within the U.S. residential market, SolarEdge held a 31 percent market share in Q2 this year, with Enphase holding 24 percent. Module-level power electronics accounted for 56 percent of U.S. residential installations in Q2, according to GTM Research's U.S. PV Leaderboard.

The future looks bright for these two: They can ride the wave of micro-electronics, which keep getting smaller, cheaper and more powerful, whereas traditional inverters are stuck with higher fixed costs. The latest round of National Electrical Code standards are also pushing installers toward a distributed model like the one offered by these products, due to the safety benefits of shutting off panels locally in case of a fire.

"It’s a major driver for added use of module-level power electronics," said Scott Moskowitz, a senior analyst at GTM Research who covers solar systems and technology. "If they're going to pay a few cents extra for rapid shutdown, many installers think they might as well get the added advantages of module-level electronics."

But both Enphase and SolarEdge face major challenges before they can get to that shiny future. Enphase announced a restructuring in September and laid off 11 percent of its workforce in the hopes of saving $20 million in annual operating expenses.

SolarEdge's stock has taken a dive, and short bets against it are rising, following market turbulence and the threat of Chinese inverter companies cutting in with cheaper products. It didn't help that major SolarEdge customer SolarCity got acquired by Tesla, which has announced an intention to switch to inverters made in-house.

These two rival companies each envision a future where their technology succeeds. The question now is how they can get there.

Market-wide upheavals

Sources at both Enphase and SolarEdge said in interviews that they are bracing for an increasingly competitive market in the near future. For the most part, the coming challenges are not of their own making -- they stem from broader trends in the solar market that both serve.

Solar module prices have fallen faster than most anticipated -- another 33.8 percent since the first half of this year, according to GTM Research -- which is great for consumers but forces solar manufacturers and installers to scramble to cut costs as competitive prices inch ever lower. That downward pressure grew stronger when demand slowed in China and the U.S. this year, triggering an oversupply of modules.

Now, solar developers are racing against each other to trim out any unnecessary expenses. Those cost cuts can come from a lot of places, including the inverters that go with the systems.

"If the folks that all the vendors are selling equipment to are getting a lot of cost pressure, the easy thing for them to do is to look to their vendors to provide cost savings," said Teff Reed, who directs the product line for microinverters at Enphase.

The primary competitors for Enphase and SolarEdge are the incumbent string inverter heavyweights, like ABB, SMA and Fronius. Meanwhile, other companies are catching on to the micro-trend in inverters. Many have failed on this path, but the success of the first movers has attracted new entrants, which Enphase and SolarEdge must now compete against. The big shadow on the horizon there is Chinese conglomerate Huawei, which is launching a DC optimizer with string inverter product next year.

"We see more and more companies realizing that [module-level electronics are] the way to go," said Lior Handelsman, founder and vice president of marketing and product strategy at SolarEdge. "The more our competition realizes that, the more they become competitors, because they are developing or adopting similar products to ours."

This situation is no doubt frustrating for the two early adopters, because they were never trying to race to the bottom on cost. The module-level power electronics market exists to offer greater functionality and distributed control than plain old string inverters. These companies went to market with products designed to do things the incumbents couldn't, which naturally started out at a higher price point.

Then the floor fell out of the solar market before microinverters reached mass scale.

The Enphase approach

Enphase has chosen to avoid a pure cost-reduction strategy. Instead, the company has taken the more difficult path of adding features while cutting costs.

"We're pulling cost out of the product, we're adding features, and we're also simultaneously trying to add features that allow our customer to save money in their operations and save time and money in their installation," Reed said.

The microinverter customers -- meaning solar installers -- aren't responding to solar market turmoil in the same way, Reed noted. The mega-installers are scrambling to cut costs, but the second- and third-tier installers, more regional and local players, aren't under the same level of pressure.

"The Tier 2s and Tier 3s are going after quality in the market; they're looking to have really long-term relationships with customers," Reed said. "That drives them toward high-power, high-efficiency, high-quality installs on roofs."

That approach matches better with Enphase's product offering. As the top dogs of the solar industry sort out their business models, Enphase is prepared to grow the "long tail" segment of its customer base. That high-quality, high-power piece of business will grow as a percentage over time, Reed predicts, because it ultimately offers savings: fewer modules on the roof, less racking, less labor, less copper to transport the electricity.

Indeed, the new IQ6 microinverter Enphase will ship in Q1 2017 was designed to save the customer money by streamlining the installer experience, Reed said. It takes 50 percent of the weight out of the cabling system and eliminates costly electrical work on the roof by having more plug-and-play features.

"We are certainly a hard cost for our installers, but we are also actively, in our product lines, chasing soft costs on behalf of our installers," Reed said.

Enphase has also turned to new revenue streams as a buffer against hard times in the residential microinverter business. The company launched an energy storage product in New Zealand and Australia that capitalizes on the distributed AC architecture of the microinverters; the battery system will be coming to the U.S. early 2017.

It also launched a commercial microinverter business, but that has never been a core driver of the strategy. Reed called it a "good enhancement business" -- as expansion in the residential business drives down the price of the equipment, it becomes gradually more competitive in the commercial sphere. Residential still makes up about 85 percent of the business.

The new version of the National Electrical Code that goes into effect in California next year will help, as it requires rapid shutdown capabilities on the roof. Enphase and SolarEdge already do that without adding components; conventional string inverters need an additional rapid shutdown box to comply, which adds to the cost of installation.

Long-term, though, Enphase's strategy hinges on the cost savings that come from high-volume microelectronics manufacturing.

"I wouldn't be at Enphase if I didn't believe that microinverters will be the dominant technology in the market -- certainly in 10 years, I would expect that microinverters are the dominant technology," Reed said. "We are going to get to a place where we cross over strings-plus-optimizers pretty easily. That's in our very near-term target."

He added that within two years or so, the company will be "within spitting range" not just of string inverters, but of where low-cost Chinese string inverters will be at that time. And, for the record, Reed contests the classification of SolarEdge's strings-plus-optimizers technology with his microinverters.

"Frankly, 'module-level power electronics' doesn't mean anything to me -- I don't see it as a real category," Reed said. "There are string inverters and there are microinverters. I think eventually there will be string inverters and AC modules."

In other words, he envisions this process of streamlining deployments culminating in fully integration of microinverters with the manufacturing of the modules themselves.

SolarEdge sees a path out

Handelsman over at SolarEdge doesn't see the current market turbulence as an existential threat, for one of the same reasons he says his company is different from Enphase.

"We are much larger in [terms of] sales, and we are profitable," he said. "SolarEdge is very strong financially, we have a very substantial amount of money from the IPO, and our profits that will help us navigate the coming turmoil."

That cash balance sits at more than $200 million, he added. That's more than a lot of cleantech startups are worth.

Beyond those cash reserves, SolarEdge benefits from diversification in the customers it serves and where it serves them. It competes in residential as well as commercial markets and is active in the U.S., Europe, the Middle East and Asia-Pacific, with offices in about 13 countries and sales in close to 100, Handelsman said.

"The ability to lean on different markets and different market segments is much broader than some of our competitors," Handelsman said. "If one market is shrinking, then we can also bring revenue from other markets."

Like Enphase, SolarEdge has to convince customers to choose its option over a traditional string inverter. That requires doing things string inverters can't do, while still bringing costs down.

"We never tried to offer the lowest-cost product in the market," he said. "We compete by value, and the value we bring to our customers comes from innovation."

That spirit of innovation drove SolarEdge to create inverters that could serve grid-tied home storage and keep the system running as backup when the grid goes down. They can also handle smart load management, maximizing a household's ability to self-consume by shifting appliance loads throughout the day. And then there are the standard improvements in efficiency, size and weight.

The DC optimizer setup, like microinverters, benefits from electrical regulations pushing for module-level control and shutdown. Looking ahead, Handelsman sees this as a trend driving inverters to become more "one with the grid," which itself is becoming more distributed and interconnected.

"In five years, you will see inverters be more complicated and more interconnected with the grid, both on the power level and on the data level," Handelsman said.

The sophisticated services that smart inverters can provide their customers will save these products from the commoditization that happened to solar PV modules, he added. Smart inverters aren't interchangeable -- they use different servers and different APIs to read their data and have different capabilities. SolarEdge includes 25 years of monitoring and cloud service with a purchase. That should buffer the company from customer defection to lower-cost alternatives that can't match the level of service.

This long-term outlook has not been reflected in the company's stock price lately, which sits at $12.90 a share, less than half of its high point this year.

"I believe that, in the long run, a company like ours, where we excel in the market, where we take market share, where we bring profit -- I think that eventually the stock market is going to appreciate that," Handelsman said.

Will only one prevail?

It's entirely possible that both companies weather the solar storm and ward off new entrants into the market to secure spots in the future of power conversion.

Both companies recognize the challenges lying ahead. Their success, not to mention continued existence, depends on the accuracy of their strategies in understanding and neutralizing those challenges, and their ability to pull off those plans.

If you ask Enphase or SolarEdge, though, it sounds like inescapable flaws haunt the other's basic product.

A microinverter architecture forfeits the per-watt savings that come with scaling up the size of an inverter, Handelsman said. "That is the reason why you do not see Enphase in the commercial market: They are irrelevant, price-wise, for commercial systems," he said.

On the other hand, Reed argues on behalf of Enphase that it can harness the economies of scale that come from more closely resembling microelectronics than other inverters, while getting smaller and more reliable more quickly. String inverters carry fixed costs that microinverters avoid, like all the metal needed for heat dissipation, Reed said.

Enphase microinverters use passive cooling, because they can dissipate on the order of several watts rather than hundreds of watts. But that requires inverters placed on the roof under the modules, which can be very hot and a potentially damaging environment to operate in, while SolarEdge puts its inverters in more comfortable spots like the garage.

Enphase adds cost and complexity by taking the expense of the AC connection and multiplying it out across each module, even though they all ultimately feed into one AC connection point below, Handelsman said. But SolarEdge adds cost and complexity by splitting power conversion across two devices. "You're taking the percentage failure rate of a string inverter, which is already relatively high, and you're adding to it the unreliability of an optimizer," Reed said.

And so on.

For two technologies that outside observers often conflate with one another, these companies have a lot to say about how they're different. At the end of the day, each perspective has some logic on its side, and the most effective judge will be the purchasing choices of their customers.

To learn more about what smart inverters portend for the storage industry, join Greentech Media for the U.S. Energy Storage Summit Dec. 7-8 in San Francisco. Now in its second year, the Summit will bring together utilities, financiers, regulators, technology innovators and storage practitioners for two full days of data-intensive presentations, analyst-led panel sessions with industry leaders and extensive, high-level networking. Learn more here.