After a barrage of wicked nor'easters this winter, Massachusetts residents probably aren't worried about having too much sun — but they should be.

Over in Hawaii, California and Arizona, midday solar generation has begun to cause major swings in the balance of supply and demand on the grid. The resulting “duck curve” has become emblematic of the logistical challenges involved in massive renewables adoption.

As it turns out, this duck infestation is migrating from the sunny, palm-lined enclaves of Venice Beach and Scottsdale to the Bay State.

“We are absolutely beginning to see a duck curve,” said Judith Judson, commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources, in an interview at the Energy Storage Association conference in Boston last week. “It shows that we're being very successful in increasing renewable energy generation, but we need to start thinking about…how [we can] match up that generation with demand.”

The telltale shape of the duck is appearing in the daily energy charts from ISO New England, the grid operator for Massachusetts and five neighboring states. The ISO has about 2,400 megawatts of cumulative solar capacity, most of which is small-scale.

Massachusetts represents almost half of the load in the territory, and the bulk of the solar capacity too. The data covers more than just Massachusetts, but the state drives regional trends.

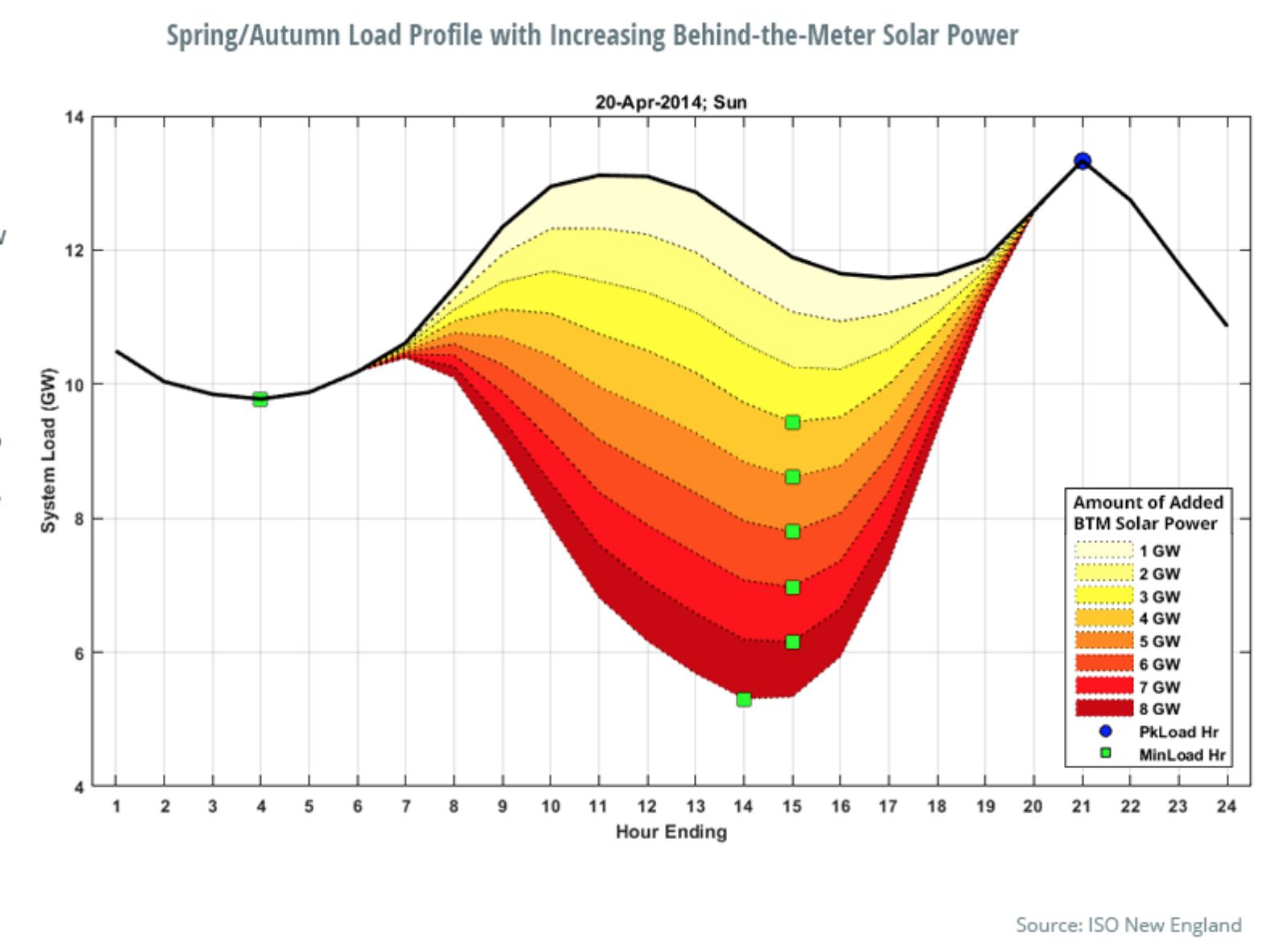

In a typical spring or fall day, load starts climbing in the early morning hours and crests by mid-morning. Total load dips through the midday hours, starts climbing again in the late afternoon, and reaches a peak around 8 p.m.

That’s fairly normal for the time of year when people aren’t cranking the air conditioning; load peaks when residents get up in the morning and when they get home from work. What’s changing is what happens in between.

Massachusetts’ 2,076 megawatts of solar capacity has already started to pull down the load in the middle of the day. That action displaces other sources of power during those hours and increases the ramp rate needed to meet demand when the sun goes down.

ISO New England will hit the 3-gigawatt level by 2019, driving down the minimum load level. (Image credit: ISO-NE)

That’s just the beginning. Massachusetts aims to nearly double its installed solar capacity in the next few years. This duck is about to have a growth spurt.

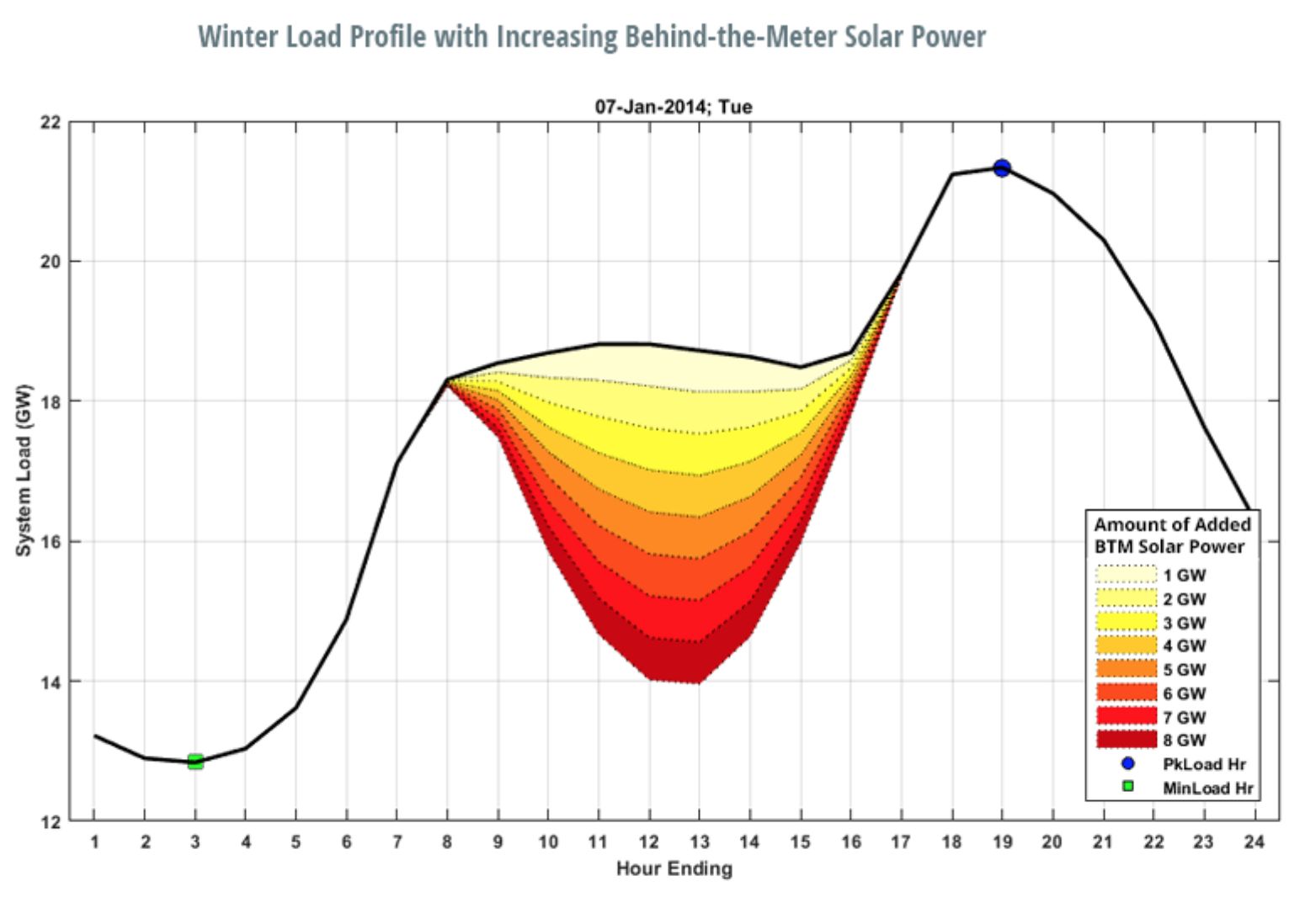

The widening gap between low midday load and high evening peak requires fast-responding capacity to keep the grid healthy. Gas can play that role, but geography and climate impose certain constraints.

The duck curve shows up in the winter months too. When cold snaps or polar vortices descend, much of the region’s natural-gas supply goes toward heating. That drives up the prices for gas-fired electrical generation, sometimes forcing a shift to other fuels like coal and oil, said Judson.

“Storage has particular value as being a solution on peak winter days — when our electric system is stressed and our heating system has full demand — as a way to be able to reliably and cost-effectively meet our energy needs,” she said.

Wintry cold snaps constrain the natural gas available to meet New England's increasingly steep evening ramps. (ISO-NE)

The expected ramping needs, combined with a coming influx of wind and solar generation, lend an urgency to Massachusetts’ recent push to expand energy storage deployments. Storage offers an alternative to natural gas for peak capacity, and can absorb surplus renewable generation, as seen in the belly of the duck curve.

Judson’s DOER oversaw a study released in 2016 that identified considerable value from storage adoption, and followed up by naming a 2020 deployment target of 200 megawatt-hours.

DOER followed up with $20 million of grant funding to 26 projects that will test various business models, generating data for the state to analyze and inform future policy around storage.

“Our goal is to have private-sector investment, but we recognized that there were barriers and there would be huge potential value to ratepayers, so it made sense to jump-start it,” Judson said.

The state has net metering and has not adopted time-of-use rates, so there aren’t many price signals to encourage residential customers to modify their solar exports.

The forthcoming Solar Massachusetts Renewable Target program will take a step in that direction by including a price adder to compensate solar generation attached to energy storage. SMART aims to add another 1,600 megawatts of solar capacity.

“Now you can have that solar stay onsite and be used later in the day and reshape the duck from behind the meter,” Judson said of the storage adder. “That’s what the incentive is designed to do, as a way to bridge the gap until we get rate design that enables that more directly.”

On the macro level, Governor Charlie Baker wants to use storage to save money during peaks, in particular those winter cold snaps.

“That is not only when we pay the most for a lot of energy sources, but it's also, in many cases, when we have some of the dirtiest sources that are available, simply because that's all that's there,” Baker said in a speech at the ESA conference.

He proposed legislation in March to create a clean peak standard, which would require a certain amount of clean energy to serve peak hours.