One or two acts of vandalism could be considered isolated incidents, but wind developers say that the increased number of attacks perpetrated against their facilities in recent months point toward a deliberate pattern.

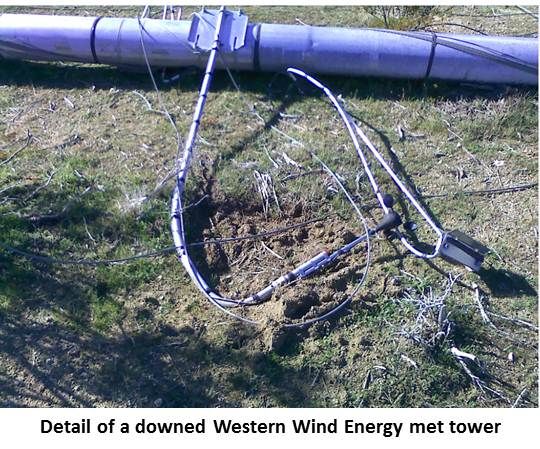

Since November, at least eight incidents of vandalism at wind farms in Southern California have been confirmed by the Kern County Sheriff’s Department. The incidents have involved AES Wind Generation, enXco Development Company and Western Wind Energy Corporation. The losses, which involve damage to meteorological equipment, amount to a total of hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Diane Oglesby, public relations coordinator for Helo Energy, said her company also had a meteorological tower taken down by vandals earlier this year.

Jeff Patterson, a consultant with Western Wind Energy Corporation and a pioneer in the Tehachapi wind development, said he has heard of 13 such incidents and is directly familiar with at least three. Met towers cost between $50,000 and $100,000 each.

These cases remain open, according to a spokesperson for the Tehachapi substation of the Kern County Sheriff's Department. The extent of the problem may also be understated because the incidents fall under the jurisdiction of at least three separate substations in Tehachapi, Mojave and Rosamond.

In the renewables-rich Tehachapi-Mojave region, some locals have come to see solar and wind as the bad guys. Could a very small number of unknown individuals be damaging equipment in reaction? How did this happen?

Call it a possible case of the longstanding conflict between state policies and local impact. California’s new and unprecedentedly ambitious renewable energy standard (RES), signed into law earlier this year by Governor Brown, requires the state’s electricity providers to obtain 33% of their power from renewable sources by 2020. Nat Parker, project manager for Element Power’s proposed combination solar and wind farm, says that the region “boasts one of the most impressive on-peak late afternoon wind resources in the state,” noting that “right when the grid needs power most, the region’s wind is peaking.”

As Dave Kerr, President of the Fairmont Town Council explained, “The wind pushes any cloud cover to the Tehachapi Mountains in the east and the San Gabriels in the west so the sun is almost always shining on the high desert floor.”

The California Energy Commission (CEC) assessments found no better place to harvest those resources than the state’s southeastern Tehachapi-Mojave region. But why should they, Mojave residents ask, have to endure change so Los Angeles has power? The Owens Valley raised the same concerns after the megalopolis claimed its agricultural water supplies for its own consumption.

No arrests have been made in the incidents and residents quoted in this story are not connected in any way with these cases. Nonetheless, their comments underscore a growing frustration with renewable developers.

"This company [NextEra] obviously does not care about our community," local property owner Cassidy Shelton added. "Hopefully, we can stop this."

State officials, arguably, have also likely sounded a bit cavalier to locals. Governor Brown recently told a conference of renewables developers that there are “some kinds of opposition you have to crush.” Promising support from his office, he added “you have to push” and stated, “We’re not going to get to the goal.”

Tehachapi-Mojave has, according to CEC estimates, roughly 1,000 megawatts of installed solar and wind capacity. At some stage of construction are another seven solar projects representing 1300 megawatts and six large wind projects representing 1700 megawatts. In the permitting process this year are an estimated 61 to 67 solar projects (ranging in size from 3,340 to 5,870 megawatts) and 20 to 29 wind projects (ranging in size from 2,500 to 6,400 megawatts).

The push is being led by those with pockets deep enough to take on the daunting development process -- companies like First Solar, which has won three quarters of a billion dollars in federal loan guarantees for its solar plans, and NextEra Energy Resources, which has proposed a $400 million wind farm.

These wind and solar projects promise jobs and revenues for a region sorely in need of them. At recent job fairs for those seeking employment at First Solar’s Antelope Valley Solar Ranch One, some 600 applications were submitted for an estimated 300 construction positions.

NextEra’s 94-turbine, 200-megawatt Blue Sky project will employ 200 to 300 people during construction. “Blue Sky is estimated to result in $90 million in new tax revenue to the state,” NextEra spokesperson Steve Stengel reported, “as well as nearly a quarter of a billion dollars [$240 million] in direct local economic benefits.”

In pursuit of the state renewables standard and economic benefits, builders dismiss opponents as NIMBYs and Luddites. In reply, locals protest that “green energy is destroying a green environment.”

Complaints have been publicly voiced about comparable action against solar power plants whose developers fail to sufficiently consider local impacts.

Patterson said he is personally familiar with the incidents at the proposed Helo, Terra-Gen and Western Wind projects. The continuous collection of a year of meteorological data is necessary, Patterson said, before a developer can decide whether there is a sufficient wind resource to build at a particular site.

Oglesby said industry insiders suspect the vandalism is by “people who don’t want to see more wind coming in.”

Patterson said he had seen vandalism elsewhere that seemed to be the work of people motivated merely by malicious intent. In Tehachapi, he said, it was different. “It wasn’t just a drive-by,” he explained. “It was somebody who knew what they were doing. They didn’t take anything, they didn’t hurt anything, nothing else was touched -- it was just drop the tower and go.”

Helo Energy has put up a new met tower -- and has retained 24/7 security to protect it.

For solar power plants, marketplace competitiveness remains tenuous; having to institute security protections will not improve it.

On the other hand, some locals don't believe many of the corporate promises that come their way.

“NextEra has no intention of doing the right thing,” local John Calvert said at a recent town council meeting. “If you don’t believe in it, fight it.”

In response to Town Council President Kerr’s warning that “there are forces out there more powerful than we can imagine,” Calvert replied, “I don’t bow to pressure.”

Again, history shows that this kind of vandalism and illegal activity is generally committed by a few individuals. Comments skeptical of development cannot be equated with criminal activity. Nonetheless, tempers are rising. And in the meantime, the companies involved say they have to take action. A proposed Terra-Gen project has been scaled back in the wake of the met tower sabotage. Other developers have retained security and persisted.