In the race for American offshore wind jobs, New York got an uncharacteristically late start.

Unlike Rhode Island, New York has no turbines spinning in the water. It does not have a ready-and-waiting offshore wind port facility, like Massachusetts, nor large amounts of free harborside space as in Virginia or Maryland. To the extent the burgeoning U.S. offshore wind industry has a capital today, most would nod toward Boston.

But the Empire State has plenty of advantages, and it’s making up for lost time.

Over the past year, New York solidified its position as not only the most important U.S. offshore wind market but also ranking among the most important in the world. Having nearly quadrupled its offshore wind target, New York now claims the largest in the nation — 9 gigawatts by 2035 — along with several of the biggest projects currently underway.

Sites like the once-forgotten South Brooklyn Marine Terminal and the proposed Arthur Kill Terminal on Staten Island may soon transform into major renewable energy hubs.

Analysts say New York’s big target and central location along the Atlantic coast make it a top contender for future offshore wind factories.

“I think a high-value component facility is coming to the U.S. much sooner than previously anticipated — most likely a blade facility, as it is a little better suited for local manufacturing than nacelle production,” said Anthony Logan, senior analyst at Wood Mackenzie. “New York would be very compelling.”

"The certainty afforded to potential manufacturers by the scale of [New York’s] offshore mandate in my opinion is more valuable than the advantages other states have attempted to secure for themselves by more direct manufacturing incentives and support," Logan added.

New York officials talk frequently and fluently about the industry. In his 2020 State of the State address this month, Gov. Andrew Cuomo confirmed plans for another 1-gigawatt-plus solicitation this year, adding to the 1.7 gigawatts' worth of projects awarded last July to Ørsted and Equinor.

Cuomo has promised $20 million toward an offshore wind “training institute” on Long Island, with the first bell slated to ring in 2021. And the state is putting up $200 million this year to revitalize its port infrastructure, to be matched by private investment.

New York has “extremely ambitious aspirations” for offshore wind, said Alicia Barton, CEO of the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA), which oversees many of the state’s renewables programs.

The state has dual motivations, Barton said. To start, it would be difficult to meet its climate and energy targets without offshore wind.

Last year, New York passed legislation requiring an electricity mix that is 70 percent renewable by 2030 (up from 29 percent of in-state generation in 2018) and carbon-free by 2040. While the state is also pursuing lots of upstate solar and onshore wind, getting that power into New York City and densely populated Long Island is a major challenge.

At the same time, New York sees offshore wind as a once-in-a-generation economic opportunity for its coastal regions.

An independent estimate last year put the U.S. revenue opportunity for offshore wind suppliers at $70 billion through 2030. A big chunk of that will flow to Europe’s existing base of factories and vessels, but over time more of it will stay at home.

Just Ørsted's and Equinor’s first projects alone are expected to bring 1,600 jobs to New York paying an average salary of around $100,000, according to state documents.

Offshore wind is a “game-changer for our economy,” Barton told GTM. “We think there’s every reason to believe that New York will be at the center of the emerging supply chain for offshore wind in the United States.”

What's on the table today

New York faces stiff competition for offshore jobs, and in many respects, it’s playing catch-up.

Massachusetts completed its Marine Commerce Terminal in New Bedford five years ago for the Cape Wind project. Improbably, Connecticut may end up with two offshore wind ports: Ørsted has promised to transform New London into a major industry hub, and Vineyard is looking to do the same just 60 miles down the coast in Bridgeport. Another 50-acre staging site is in the works at Baltimore’s Sparrows Point.

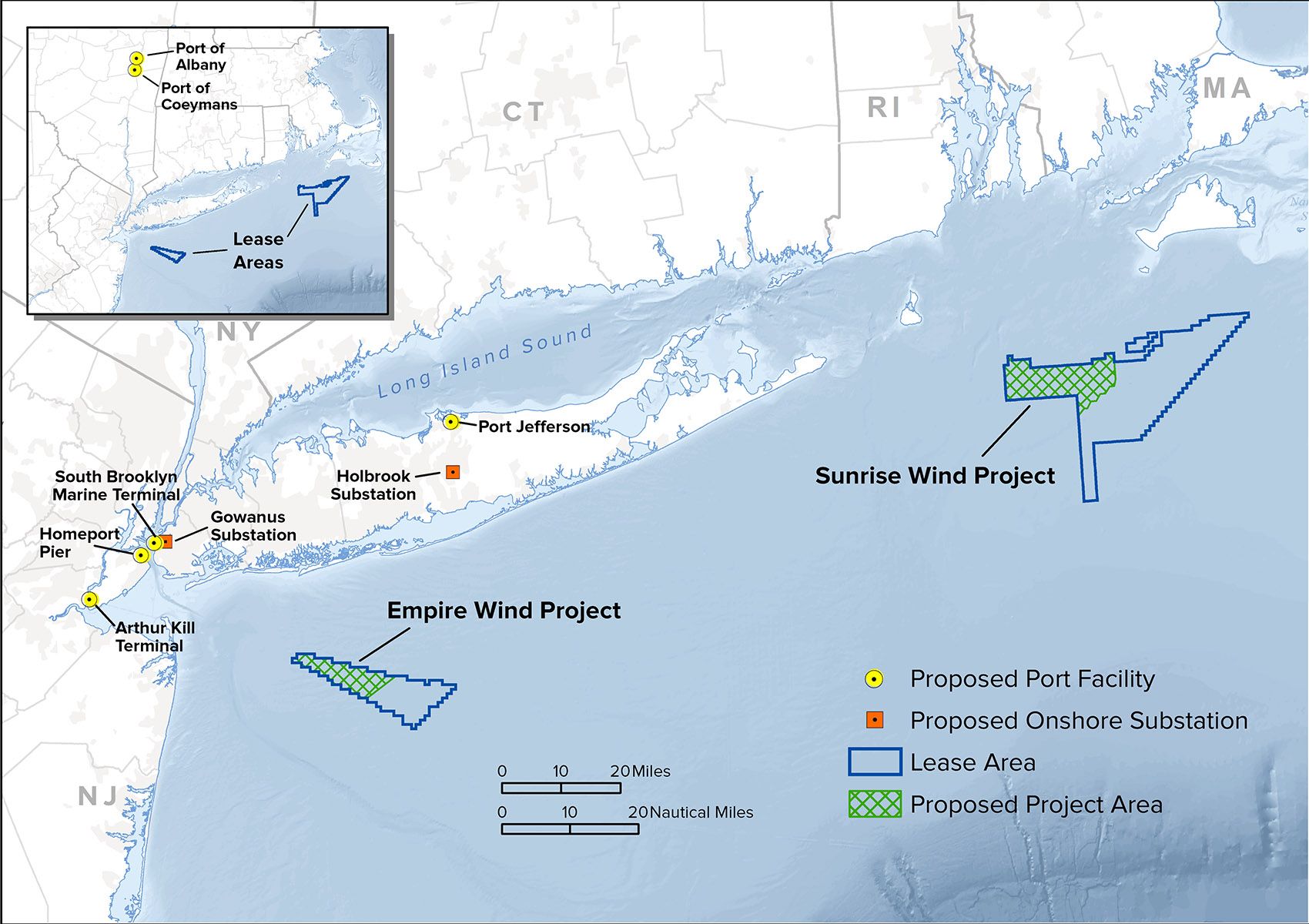

New York has several of its own irons in the fire. In its winning bid last year for the 880-megawatt Sunrise Wind project east of Montauk, Ørsted committed to building an operations and maintenance hub in Port Jefferson, Long Island. O&M jobs are among the renewables industry’s most durable over time.

New York wants more offshore wind zones tendered out near Empire Wind's project. (Credit: NYSERDA)

Equinor’s in-state plans are even grander for its 816-megawatt Empire Wind project. The Norwegian oil giant is looking to establish its own O&M base at the South Brooklyn Marine Terminal, a container and cargo facility that began to undergo a state-led revitalization a few years ago.

Additionally, Equinor plans to source the huge foundations for its turbines from the Port of Coeymans, near Albany along the Hudson River. And it’s considering Staten Island’s Homeport Pier — largely dormant since a brief stint as a naval base in the 1990s — as the staging area for the foundations before they head out to sea.

The commitments from Ørsted and Equinor could grow as their projects move forward, said Barton, noting that Equinor has not yet decided on its turbine supplier. “Once they do, we certainly will be aggressive in trying to work through components for localization related to the turbine supply contract," she said.

States have taken varying approaches to incentivizing local benefits. At one end of the spectrum, Maryland explicitly required developers to create jobs. New York took a more hands-off approach in its first solicitation, putting a 20 percent emphasis on local content compared to 70 percent on price. Unsurprisingly, New York will pay nearly 40 percent less for its offshore wind power than Maryland, at around $84 per megawatt-hour in levelized terms.

Offshore wind prices are expected to continue falling in the years ahead as technology improves, the supply chain localizes and additional lease areas catalyze competition among developers.

When it comes to local factories, “as much as states would like to dictate where things go, the market is ultimately going to make those decisions,” said Liz Burdock, CEO of the Business Network for Offshore Wind, an industry group.

So where are the turbine factories?

Among the biggest prizes in the supply chain are plants for turbine nacelles and blades. The goal post, however, seems to have shifted as to when the U.S. might expect such a factory.

All three of the world’s main offshore turbine suppliers outside of China — Siemens Gamesa, MHI Vestas and GE — have now secured big U.S. orders. But they remain cagey about committing to an American factory, saying they need to see policy certainty and a predictable long-term market before making such a momentous investment. GE has called it "premature" to talk about the timing of bringing a factory to the U.S.

On the market side, the U.S. project pipeline now looks very impressive; its current size and geographic reach would have shocked most industry observers just a few years ago. WoodMac expects at least 16 gigawatts of capacity installed by 2028, with a multi-gigawatt annual market from 2024 onward.

Policy certainty, on the other hand, is in short supply. Although the Trump administration remains outwardly supportive of offshore wind as part of its “energy dominance” agenda, recent signals have been mixed.

Vineyard Wind’s pioneering project for Massachusetts was knocked off schedule by an unexpected permitting delay; the developer continues to wait for the all-clear from the Interior Department’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM).

Meanwhile, government plans to lease additional offshore wind zones in the New York Bight area have moved slower than hoped. Industry sources say the lease auction now looks unlikely to happen until late 2020 or 2021.

A BOEM spokesperson said in an email that the government “anticipates leasing additional areas in the New York Bight over time” but added that there's “no formal schedule for future leasing.”

Uncertainty around the timeline of federal permitting may be the biggest headwind for securing American factories, NYSERDA’s Barton said.

“Once we start to see the first or second projects clear those permitting processes and we have a clearer sense of the timeline, I hope that will be the last remaining barrier to some of these major manufacturing commitments,” she said.

The small problem of the Verrazzano Bridge

Among the obvious impediments to a New York-based supply chain is the iconic Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge.

The Verrazzano links Staten Island to Brooklyn and ranks as the Western Hemisphere’s longest suspension bridge. But with just 65 meters of air clearance, it’s a problem for vessels transporting huge turbines or foundations out of New York Harbor.

New York's bridges "aren’t insurmountable" for the potential supply chain, said WoodMac's Logan, but other things being equal, they "certainly knock [New York] down a peg in attractiveness."

New York's Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge, seen from Staten Island, with Manhattan in the distance.

One infrastructure developer, Atlantic Offshore Terminals (AOT), already has a workaround in mind in the form of the proposed Arthur Kill Terminal.

AOT controls a 30-acre piece of land along the southwestern corner of Staten Island — unique among New York sites in being on the ocean side of the Verrazzano. The plan is to transform the site into a major offshore wind hub.

“There are thousands of wind turbines to be installed off the New York Bight, and there isn’t a port currently to support that in the region,” said AOT’s chief executive Boone Davis, who served previously as GE’s project manager for the Block Island Wind Farm.

The Arthur Kill Terminal is “the only site between Montauk and Cape May [at the southern tip of New Jersey] that in our view is suitable for development into a new port supporting this very important task.”

The terminal would be able to handle 800 to 1,100 megawatts of capacity going out to sea each year, Davis told GTM, and the facility could be ready by 2024. The project, like other New York sites, is seeking funding from the state.

A boom without the jobs?

With the U.S. offshore market coming into focus more quickly than the supply chain to support it, there's a danger of disappointment around local jobs, some experts warn.

The consensus is that things will unfold very differently than they did in Europe, where the supply chain is largely focused around a handful of “super ports” in places like Denmark’s Esbjerg or Germany’s Bremerhaven.

Instead, the far denser population of the East Coast means that any U.S. supply chain would need to fan out much farther and across more sites, presenting difficulties but also potential opportunities.

“The challenge for New York, and it’s the same almost everywhere on the East Coast north of Maryland, is that the amount of waterfront acreage that’s available for conversion for offshore wind use is limited,” said Jay Borkland, a senior engineering manager at Lloyd’s Register.

“Even a 150-acre site, while that may seem like a lot, is a drop in the bucket compared to Esbjerg or Grenaa or Cuxhaven or Bremerhaven — those are hundreds to thousands of acres each," Borkland said.

Even smaller port sites can take years to develop. In the meantime, a number of big American offshore wind farms are supposedly just around the corner.

“Either we’re going to continue to import an awful lot of components from Europe, or there’s going to have to be an incredible flurry of activity to move U.S. port and infrastructure development forward," Borkland said.

The U.S. market has picked up considerable momentum, but "there’s a danger that the entire East Coast portfolio of offshore wind farms could be supplied from elsewhere," he said. If that scenario comes to pass, "We’d have squandered this great opportunity.”