New York City got a surprise last year after an energy disclosure report showed that some of its 80-year-old buildings were outperforming LEED-rated buildings. The report illustrated why energy benchmarking laws can be effective tools to help municipalities and building owners target how they take action. Sometimes the target is not what was initially expected.

Seattle is the latest city to issue data on its buildings. Officials just logged data on 94 of Seattle's municipal buildings, including City Hall, libraries, police stations and the 62-story Municipal Tower. While not earth-shattering in its conclusions, the report showed some interesting variations in how municipal facilities are operating.

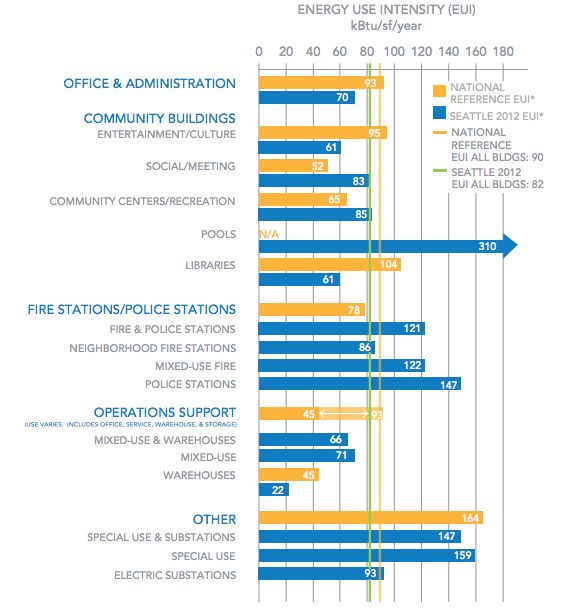

One of the more interesting facts from the report: Seattle's libraries are 42 percent more efficient than the average U.S. library. And the city's downtown central library uses 50 percent less energy than the nationwide average.

The city's police stations and fire stations are a different story. The report shows that Seattle's fire stations use 10 percent more energy than the U.S. average, and that police stations are using almost double the energy that an average police station does.

Overall, however, many of the city's buildings are performing quite well. The Seattle Municipal Tower, a downtown office building hosting more than 3,000 people, uses 40 percent less energy than similar-sized buildings in the U.S. The entire downtown campus, which features the Municipal Tower, City Hall, the Justice Center and the central library, is also performing better than the national average.

Here's a breakdown of how all the facilities being tracked compare to the national average:

This is the first time that Seattle's building energy consumption has been made public. The city's 2010 benchmarking law requires private building owners to disclose energy data with tenants and during real estate transactions. More than 90 percent of building owners with facilities more than 50,000 square feet in size are reporting their consumption so far. And starting in April, buildings with 20,000 square feet or more are now required to report energy consumption to the city.

Seattle is one of a number of cities that now require building owners to disclose energy use. Austin, Boston, the District of Columbia, Minneapolis, New York, Philadelphia and San Francisco have all passed similar benchmarking laws.

Seattle's mayor has set a target to reduce energy use in municipal buildings by 20 percent over the next seven years. Since 30 percent of the city's buildings were constructed before 1980 and there will be very few new large buildings through 2050, Seattle's focus will be on retrofitting existing building stock. This report gives the city a much better understanding of which facilities to retrofit.

And if Seattle's mayor wants to enforce his 20 percent target, he now knows one major culprit to target: the police.