The rapid growth of solar power, and the promise of microturbines, battery storage and other distributed technologies, is engendering change and new opportunities in the utility world. Many are looking at the cell phone in their pocket and wondering what lessons can be learned from the transformation continuing to sweep the world of telecommunications.

The always quotable David Crane, the CEO of the independent power producer NRG Energy, said that thanks to distributed generation, “consumers are realizing they don't need the power industry at all.” In an interview with Bloomberg TV, he said:

“The energy industry is about to make that jump to being an information-technology-based industry like the telephone industry did 25 years ago. Thirty years ago the telephone industry and the power industry were considered twins. You don't think that way now, because they've [the telephone industry] done so much and we've done so little.

“The change is going to be about empowering the end-use consumer to make energy choices for themselves rather than having the government and the public service commissioners tell them how they're going to get the power, who they are going to get it from, and how it's going to be produced and delivered to their home.”

The Edison Electric Institute, in its paper Disruptive Challenges, sees the same threat. “Who would have believed ten years ago that traditional wire-line telephone customers could economically ‘cut the cord?’”

EEI points out that solar is now “in the market” for 16 percent of U.S. retail electricity sales (where rates are at or above $0.15 per kWh), and that this could double by 2017, competing for $170 billion of annual utility revenue.

“When customers have the opportunity to reduce their use of a product or find another provider of such service, utility earnings growth is threatened.”

While their proposed solutions are to undermine distributed generation by changing the rules, we think that is a losing proposition -- and not in the public interest. The forces of consumer demand and technological innovation make change inevitable. It is better to plan for it than to resist.

Lowering barriers to entry

And there is plenty to plan for. A power system with much higher levels of distributed renewable generation is radically different in certain ways.

One revolutionary aspect of distributed generation is that it bypasses a main barrier to innovation in the power sector: the need for large-scale power plants with high capital costs. The massive investments needed to build new power plants have always been a barrier to entry, limiting competition to regulated utilities and to large independent power producers (so-called “merchant” generators).

To minimize investment risk, these merchant generator companies (some of which began as affiliates of utilities) have relied almost entirely on natural gas power plants, since the capital costs are low (less than $1 per watt) and the fuel costs set the market price for power. So when gas prices are high, power prices will be high, allowing the power-plant owner to pay for the higher gas prices.

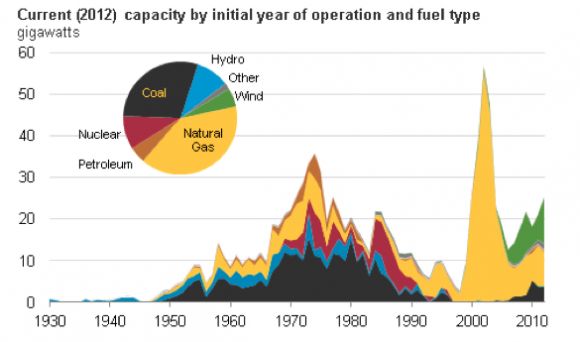

Utility restructuring opened the floodgates for this kind of investment. The uncertainty of the 1990s, as policymakers debated deregulation, gave way to an explosion of construction. Over 50,000 megawatts of new utility-scale gas-fired plants were built in one year a decade ago. New merchant generation companies like Enron, Dynegy, Calpine and AES rushed to compete with each other for new customers.

Source: Energy Information Administration

Now there is a growing wave of investment in distributed generation. But there are some important and radical differences.

With distributed generation, there are millions of potential investors and owners. Anyone with a roof, rural residents with an open field, farmers with livestock, military bases, data centers, sewage treatment plants, factories -- the list is almost endless.

Their motivations are endless too -- to save money, to increase the efficiency of their operation, as a hedge against power outages, as protection against military attacks, cyberattacks or natural disasters, or to reduce their environmental footprint.

Because these investment decisions are individually small, they don’t need to amass billions from risk-averse banks and investors. They don’t need permission from financiers. The barriers to entry are only those created by regulators and utilities.

It is also very different for the developers and sellers of the new technologies. With traditional power plants, there were few sellers and few buyers. Only a handful of companies could amass the capital and expertise needed to build complicated central station generation technologies, and only a few hundred companies own big power plants in the U.S. General Electric and Siemens, for example, are among the world’s largest corporations, employing a combined 670,000 workers.

Because few companies were selling few products to few buyers, there was limited competition, not much pressure, and not much “learning by doing” that drives new innovations down the learning curve. Hence, as David Crane puts it, utilities have been “the least innovative industry in America, maybe the world, in history.”

Utility evolution

Distributed technologies are completely different. They are “manufactured” technologies, which means they are built on assembly lines by the thousands or millions. They are sold to potentially millions of customers. And the barriers to entry for manufacturers are small, at least for some technologies. The solar industry is the quintessential example: there are hundreds of companies around the world making solar panels, causing competition so fierce that the largest maker has a market share of only 9 percent.

So while the scale of capital and engineering needed for the old central-station system made innovation difficult, innovation is an imperative for new modular technologies.

Angus McCrone, chief editor of Bloomberg New Energy Finance, has compared the electricity transformation underway to the “extinction event” at the end of the Cretaceous period that led to the demise of the dinosaurs and the rise of mammals. Mammals -- “small, fast-breeding, flexible, able to work in groups” -- were able to innovate and adapt in a way that dinosaurs were not.

Action plan

This is a vivid metaphor for the power sector, but what exactly are the dinosaurs and what are the mammals? We think it is an exaggeration to say that utilities are headed for extinction as we all go off the grid. The power grid continues to offer consumers compelling benefits, and distributed generation is more likely to enhance the grid than to replace it. Someone will have to run the system, perhaps as a “smart integrator” of a multifaceted power landscape.

Instead, we think the dinosaur is the traditional utility business model, which relies on utilities selling ever more power to passive consumers. Power companies will have to adapt and innovate to offer consumers the products and services they desire, lest they face the same type of creative destruction that has revolutionized countless industries in the U.S.

Ron Lehr explores new utility and regulatory models in another paper in the America’s Power Plan series. (And for an in-depth discussion on the series, listen to this week's Energy Gang podcast, "Will This Plan Save Utilities From Themselves?")

To capture the benefits of distributed generation in ways that can benefit all consumers and that will enhance the value of the interconnected grid, America’s Power Plan lays out a set of recommendations that includes the following elements.

Net Energy Metering: Energy consumers need a simple, certain and transparent method for pricing the power that they supply to the grid. Net metering has served this purpose well and should be continued so that the customers and suppliers of distributed generation systems know that this foundational policy will be available in the long run. Decision-makers can address cost-shifting concerns over net metering through the same type of cost-effectiveness analyses that have been used for many years to assess other demand-side resources such as energy efficiency and demand response.

Shared Renewables: Many energy customers do not have a rooftop suitable for the installation of solar panels or a yard large enough to site a wind turbine. Shared renewables programs can address this problem through the development of larger, but still distributed renewable generation projects connected to the distribution system at the wholesale level, with the power output distributed to subscribers or community members. Shared renewables programs should be developed so that all energy consumers are able to participate in clean energy markets.

Wholesale DG: Distributed generation doesn’t have to be on the customer’s side of the meter, nor does the output need to serve specific customers. It can also be deployed as small power plants, providing wholesale power to utilities. Wholesale DG can help utilities to meet their state’s renewable portfolio standard goals, to hedge against the risks of developing large-scale generation and transmission projects, and to respond quickly to load growth. A variety of administrative or market-based pricing mechanisms can be used to support wholesale DG, with long-term contracts essential in order to allow these capital-intensive projects to be financed.

Interconnection Standards and Local Permitting: Too much red tape can present a major barrier to distributed generation, raising “soft costs” like permitting and customer acquisition. Regulators and local agencies should adopt best-practice interconnection standards and improvements in the permitting process for DG as ways to remove these barriers to DG deployment while still ensuring safe and reliable installations.

Integrated Distribution Planning: DG can reduce transmission and distribution costs, but only if utilities integrate DG into their planning for delivery networks. IDP is a coordinated, forward-looking approach under which utilities plan in advance to upgrade or reconfigure certain circuits that are expected to have DG added in the near future, and make the associated costs known to the market with far more transparency than is common today.

Distributed generation can create important benefits for consumers, the grid, the economy, and the environment. And the pace of change will only accelerate, as companies and entrepreneurs innovate. With smart policies, we can prepare for change rather than fight against it, and capture the benefits of advanced technologies while avoiding the disruptive side effects that too often bedevil innovation.

Watch an interview with Joe Wiedman of the Interstate Renewable Energy Council below:

***

America’s Power Plan is a response to the rapid changes in the power sector being driven by consumer demand for clean energy, new technologies and policy. Rather than a one-size-fits-all prescription, America’s Power Plan is a toolkit to help facilitate a discussion about how to move to a cleaner energy future.

Joseph Wiedman represents the Interstate Renewable Energy Council. Tom Beach is the owner and principal consultant of Crossborder Energy. Bentham Paulos is the project manager for America’s Power Plan.