The looming international trade war over solar doesn’t have to happen if the U.S. and China can come to realize that each has a unique role to play in a single global solar industry.

The problem is that “each country extends different assistance mechanisms,” according to the MIT report, A Duel in the Sun: The Solar Photovoltaics Technology Conflict Between China and the United States. And neither country effectively and transparently assesses “the cost-effectiveness of the assistance.”

The differences in support coupled with the lack of transparency have led to two views of the conflict, according to report authors John Deutch and Edward Steinfeld of MIT. One view, held mostly in the West, is that China’s growth came from a central government decision to use subsidies and unfair trade practices to take global control of the solar industry.

This view blames the collapse in solar module prices on a tactical willingness by China to accept short-term economic loss on the way to establishing long-term dominance in the sector.

Believing this, U.S. PV manufacturers won import tariffs against Chinese cell and module manufacturers, and now the EU is poised to follow suit.

The Chinese responded, according to the MIT report, by:

- Calling back support for Chinese companies invested in the U.S.

- Bringing counter allegations at the World Trade Organization

- Threatening tariffs on polysilicon imports from the West to China

The other view is that Chinese entrepreneurs, mostly expatriates returning to China with experience in the global semiconductor industry, seized leadership in a competitive market. Using newly available private capital and state-of-the-art production methods, they mustered municipal and provincial incentives to scale, supported by rising European solar demand.

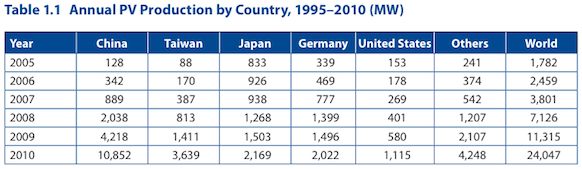

Source: A Duel in the Sun: The Solar Photovoltaics Technology Conflict Between China and the United States

With the European financial crisis, demand collapsed. To sustain an industry that had begun to provide valued jobs, China’s central government stepped in. “Previously indifferent to the sector,” the MIT report noted, it began “to bail out producers and stimulate domestic PV demand.”

Though China is a single-party authoritarian state, the MIT authors noted, official policy often does not produce results because:

- Provincial and municipal governments take their own courses

- Large state-owned entities (SOEs) leverage insider networks to avoid regulation

- Government-imposed market-based mechanisms and five-year plans often fail

- The China Development Bank and state-owned commercial banks can exercise independent control

These factors compromised the Chinese central government’s early PV sector successes. The 2009 Golden Sun program produced 4 gigawatts of growth in 2011, according to the MIT report, but the feed-in tariff has not shown the same results. “It is by no means clear that the [National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC)] or any other central agency has the capacity or desire to force the state grid company to participate in the FIT program.”

The 12th Five-Year Plan on solar power development called for 21 gigawatts of solar, mostly PV, by 2015, and 50 gigawatts by 2020. But it did not make clear where financial support would come from.

The MIT authors listed five major supports for PV in the U.S.: The Advanced Energy Manufacturing Tax Credit, the Loan Guarantee Program, the Investment Tax Credit, the Treasury Cash Grant Program, and DOE programs such as the SunShot Initiative that provide purpose-focused grants.

But much of this support was the result of the 2009 Recovery Act and is unlikely to be re-upped. More importantly, there is no clear, transparent and complete “quantification of the benefits of these subsidies,” the report noted.

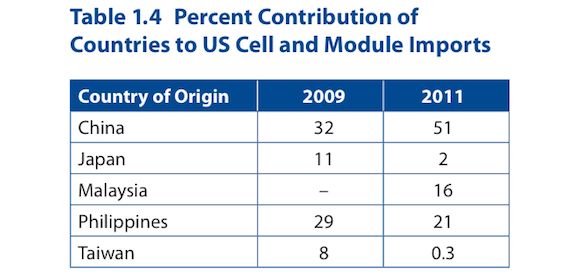

Source: A Duel in the Sun: The Solar Photovoltaics Technology Conflict Between China and the United States

In short, the report makes it clear that nobody really knows exactly how much support PV solar gets in the U.S. or China or how much it will continue to get. And, the report added, “it is by no means clear what assistance mechanisms are most cost-effective.” But a fight over the “fairness” of each other’s government supports could have global consequences, it added.

“Chinese PV manufacturers and high-end equipment and materials providers from the United States and elsewhere are interdependent and form an important global ecosystem for innovation. A slowdown in the growth of Chinese PV manufacturing implies a sharp decline in business for high-tech firms in the United States and elsewhere that currently develop the technology on which future progress of PV depends.”

If that happens, the report warned, it would take “several years” for the world’s PV markets to shrink capacity, expand demand and firm up prices. To avoid the worst, the MIT authors made two recommendations:

- Because they found no evidence “that government subsidies, low labor costs, or stolen technology are sufficient factors to explain the apparent Chinese advantage in manufacturing," the authors reported, U.S. firms that can’t match Chinese cell and module manufacturing competitors “should focus on the many other attractive parts of the PV supply chain, especially those with higher profit margins.”

- Both sides need to consider the goals and effectiveness of their PV support mechanisms. They are sustainable if they increase “cross investment, technology transfer, and joint development.”

“There is a global public good in subsidizing PV technology development," the MIT report concluded. "The tight linkage between U.S. and Chinese PV firms raises the question of whether there are practical mechanisms of public support that could advance the global PV enterprise better than the separate efforts of each country.”