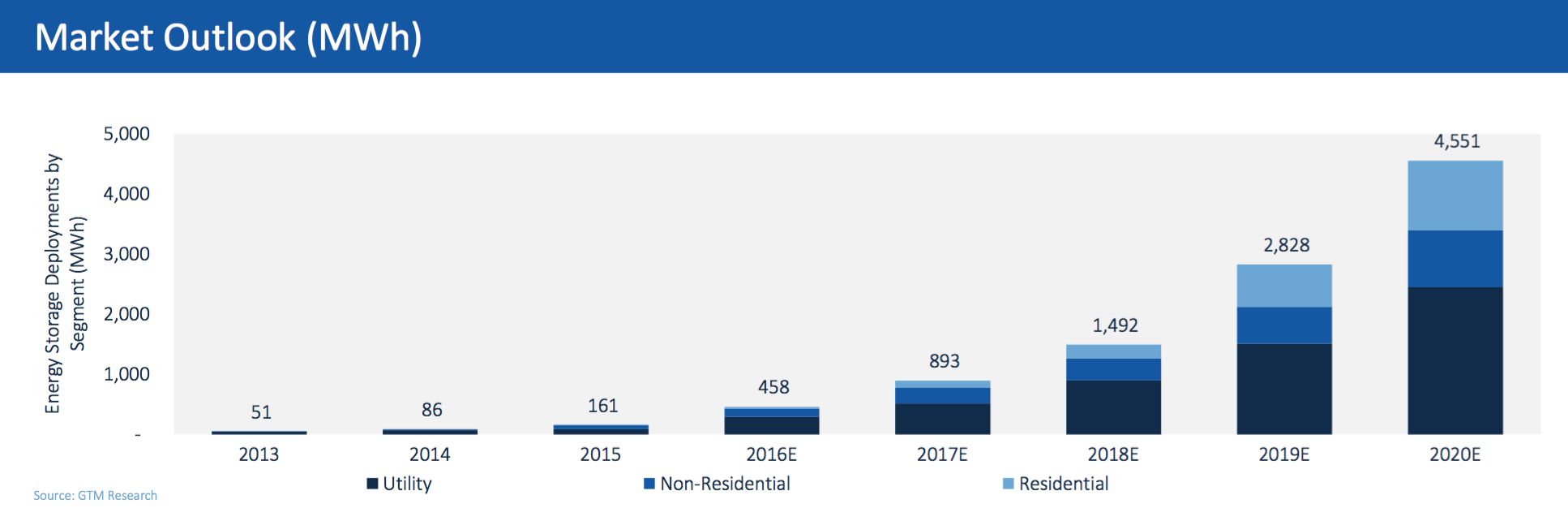

In 2020, America’s energy storage market will likely surpass 1.6 gigawatts -- making it 28 times bigger than it was in 2015.

The U.S. market in 2020 will be defined not just by higher volumes, but by diversity in project types. While large storage projects on the utility's side of the meter currently dominate deployments, smaller batteries in homes and businesses on the customer's side of the meter will become the biggest segment in terms of capacity in the next four years.

According to the latest figures from the U.S. Energy Storage Monitor produced by GTM Research and the Energy Storage Association, 187 megawatts of storage capacity was installed in the U.S. last year. That far outpaced behind-the-meter storage, which amounted to 34.4 megawatts.

By the end of the decade, however, distributed batteries will edge out centralized systems in front of the meter. Behind-the-meter batteries in homes and commercial sites will amount to 841 megawatts of capacity; front-of-the-meter storage will amount to 821 megawatts of capacity. (In energy terms, utility-scale projects will still represent 54 percent of the market, giving that sector a bit of an edge.)

That projected shift indicates that the nascent customer-sited battery segment is maturing. A broad range of manufacturers are bringing distributed systems to market; more solar and energy services companies are expanding into on-site battery offerings; financing options are improving; costs are coming down; and some utilities are starting to experiment with offering solar-plus-storage to their customers.

The trend is also a reflection of how regulation in the electric sector is evolving and altering the course of technology development.

“There are two big factors at play: rate changes and fees pushed by utilities concerned about net metering, and more sophisticated market rules that allow distributed batteries to play in the market,” said Ravi Manghani, GTM Research's senior storage analyst.

Aside from a few residential pilots, virtually all behind-the-meter storage in the U.S. is being deployed in the commercial and industrial sector, where high daytime demand charges in select states make batteries attractive to large-scale power users.

However, these demand charges -- as well as other types of fixed charges, time-of-use-rates and tariffs to encourage self-consumption -- could become increasingly common in the residential sector as utilities seek alternatives to retail net metering for solar customers.

"I would certainly agree that residential demand charges and other rate charges appear to be catalysts for storage and solar-plus-storage," said Alexander Pischalnikov, an energy and utilities expert at PA Consulting Group.

Pischalnikov pointed to Hawaii, where regulators established new net metering rules last year. One net metering tariff compensates customers at the wholesale rate, rather than the retail rate. The other self-supply option allows customers with PV and battery systems to speed up their interconnection process, but they do not get compensated for any electricity fed into the grid.

"Self-supply has become a pretty compelling proposition in Hawaii," said Pischalnikov. "Installers are very much reacting to the changing business environment, and you're starting to see more joint bundled service offerings."

It's still too early to say whether residential demand charges for solar customers imposed by Salt River Project in Arizona will boost battery storage, or whether Nevada's drastic cuts to net metering will encourage self-supply. The economic value remains minimal, and vendors haven't developed sophisticated sales strategies.

"It takes time for companies to get into these markets, educate local installers and understand local interconnection requirements. There’s always a delay and a lag. You’re seeing some of that going on," said GTM Research's Manghani.

Meanwhile, a number of states and utilities are working on policies aimed at helping distributed storage.

California is developing clearer market rules that allow companies to aggregate behind-the-meter batteries. New York is putting together similar rules designed to enable customer participation in the energy market through its Reforming the Energy Vision plan. And Colorado, Massachusetts and New Jersey have all established incentive programs for distributed batteries.

On the federal level, the Department of Energy is funding behind-the-meter storage projects through its grid modernization initiative -- potentially expanding applications across a greater geographic range. "I think DOE will spur opportunities across other states that may not have sophisticated rules for storage," said Pischalnikov.

The multi-year extension of the federal Investment Tax Credit (ITC) will also be fuel the growth of storage. Although IRS guidance on how storage qualifies for the ITC is still in the works, developers are taking advantage of the credit for solar-plus-storage projects on a case-by-case basis. Clear rules could be a boon for the storage industry.

All of these policy and regulatory factors -- some proactive and some reactionary -- are coming together to spur behind-the-meter storage in the coming years.

The big unknown will be how individual utilities embrace the technology. Will they see self-consumption as a threat to their business? Or will they treat distributed batteries like a resource that can help balance the grid when aggregated? It will likely be a combination of both.

"Utilities are generally curious and interested to test the capabilities of storage. But there's still this huge amount of hype and uncertainty around the technology. We expect to see much more dialogue and many more pilots in this sector before there is a big commercial push," said Pischalnikov.

This article is part of a Next Generation Utility series at GTM supported by PA Consulting. Find more news and analysis on the subject here.