Hawaiian Electric is trying out all sorts of distributed energy assets to help it manage its solar-impacted island electricity system, including behind-the-meter batteries, plug-in electric vehicles, and smart-meter-enabled energy disaggregation. But one of the cheaper grid tools at its disposal could be the ubiquitous electric water heater.

That’s the prospect being tested under Hawaiian Electric’s Grid-Interactive Water Heater (GIWH) initiative. Launched in September, the project will seek to deploy networked, utility-responsive water heaters in small and medium-sized businesses on the island of Oahu, in order to test their ability to help with everything from multi-hour load-shifting to second-by-second grid regulation.

Hawaiian Electric revealed the project in a November filing with the Hawaii Public Utilities Commission, which didn’t provide any details on the scope or scale of the project. But it did name two technologies it would be evaluating -- the “Variable Storage Water Heater (VSWH) and Grid-Interactive Energy Thermal Storage (GETS).”

The first technology, VSWH, corresponds to the “variable capacity water heating” patent issued to Sequentric Energy Systems, a company that’s been working with Battelle on networked, grid-responsive water heater pilots with mid-Atlantic grid operator PJM. Battelle filed comments with the Hawaii PUC in September, describing its “real-time aggregation engine that effectively cycles fleets of GIWHs in response to signals (e.g., automatic general control, wind firming) from the grid operators.”

The second technology, GETS, is the moniker that Steffes Corp. has given its “dynamic dispatch” technology for managing distributed water heaters as fast-acting grid resources. Steffes has been working alongside Sequentric and other technology providers in Canada’s PowerShift Atlantic project, as well as in the DOE-funded Pacific Northwest Demonstration Project.

“The idea is that Hawaiian Electric is going to run a one-year trial to determine what, if anything, these technologies can do to help mitigate the challenges in Hawaii,” Kelly Murphy, Steffes’ smart grid business development specialist, said in a Tuesday interview.

Remote-control water heaters have long been a staple of demand response programs across the United States, but they’ve primarily been limited to broadcast-style on-off commands meant to ease peak loads in emergencies.

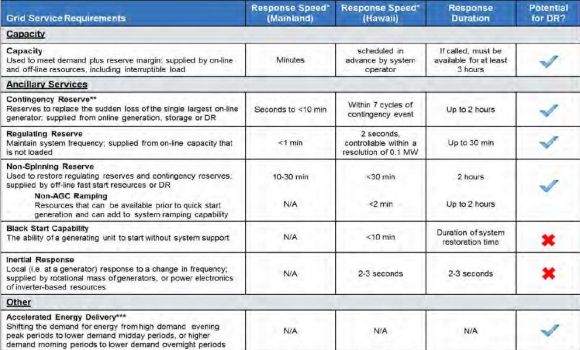

But Hawaiian Electric wants to test the smart water heaters’ abilities to meet a wide range of grid ancillary services (PDF), including frequency regulation and contingency reserves, meant to “replace the sudden loss of the single largest on-line generator” on the island, as shown in the following table.

Water heaters could also help Hawaii solve its “Nessie curve” problem, Murphy noted. That’s the term Hawaii’s grid planners have come up with to describe the midday boost in solar power, and subsequent dropoff in late afternoon and evening, that are disrupting traditional load curves on the island, much like California’s “duck curve” is starting to do in that state.

“If you can take a sizable load like water heating, and you start moving it around so that it’s absorbing more solar energy, you’re going to have a lot more room to move around,” he said.

Hawaiian Electric is also applying its water heater experience to its Integrated Demand Response Portfolio Plan. That’s one of the initiatives that the Hawaii PUC ordered the utility to undergo earlier this year to adapt to a future that includes a lot more distributed, customer-owned energy assets, primarily rooftop solar PV, as well as a much higher level of intermittent renewables.

Hawaii has no natural gas, making electricity the fuel of choice for heating water in homes. Water heaters make up most of a typical Hawaii household’s electric bill, and are responsible for about one-seventh of the islands’ peak demand, making them good targets for energy management.

Water heaters can’t discharge electricity like batteries can, and they have limitations as to how long they can be turned off before the lack of hot water starts causing problems for the customers who rely on them. But they’re also a lot cheaper than batteries, and they’re already installed in almost every home and business on the island. “We are finding out that these devices can be counted on to perform a lot of services, a lot cheaper than alternatives,” Murphy said.