The German government has responded to the next big challenge in its energy transition -- storing the output from the solar boom it has created -- by doing exactly what it has successfully done to date: greasing the wheels of finance to bring down the cost of new technology.

Over the past five years, Germany has been largely responsible for priming an 80 percent fall in the price of solar modules. Now it is looking at bringing down the cost of the next piece in the puzzle of its energy transition: battery storage.

At its disposal is the giant state-owned but independently run development bank KfW. In the clean energy space, it performs a similar function to Australia’s recently created (and likely doomed) Clean Energy Finance Corporation, but at a scale that is not contemplated in most countries, with the possible exception of China.

It has assets of more than €500 billion, and lent €73 billion last year, with one-third of that targeted at renewables and climate investments. Over the past three years, it provided €24 billion in loans for energy efficiency investment in homes, leveraging a total investment of €58 billion, helping insulate and seal more than 2 million homes, employing 200,000 people a year, and saving more than 150 million tons of carbon.

Six months ago, it began a new program to finance the introduction of battery storage into homes and small business, which it says is absolutely essential if the “Energiewende,” the German expression for its energy transition, is to successfully move to the next phase and beyond 40 percent renewable penetration.

The energy storage financing program has generated a higher than expected response. Already, 1,900 homes and small businesses have applied for loans and grants (provided by the Environment Ministry) to install new solar systems and battery storage systems in their homes. Around €32 million in loans have already been allocated, as well as €5 million in grants, about 10 percent of the sums allocated in the initial phase of the program.

Unlike the subsidized uptake of solar PV enabled by the deployment of generous feed-in tariffs, the support mechanism for energy storage is more cautious. Indeed, KfW is looking for investors who are willing to take a loss on their investment.

“The market for energy storage systems is very young, batteries are still very expensive…and the economics don’t yet work,” said program manager Dr. Holger Papenfuss in an interview.

In fact, even with the assistance of the loans and grants, it is still not economically viable, which is why KfW has stepped in to ensure that the commercial banks provide the funds for development.

The program is relying on early adopters and renewable pioneers -- the same consumers that were the first to get into electric vehicles, or to procure solar panels a decade ago -- who have the money and are willing to accept a negative return on their investment. Right now, Papenfuss said, people would be better off selling power to the grid.

So what’s motivating them? The prospect of being independent of the large power producers and the ability to hedge their bets in the face of rising electricity prices.

According to Papenfuss, households will spend between €20,000 and €28,000 on solar and batteries, depending on the size of the system. The battery component (the program targets lead-acid and lithium-ion batteries) is between €8,000 and €12,000, and the grants for this average around €3,000 (or about 30 percent of the battery cost).

The average loan for the whole system is around €17,000, but it is not offered at a discount. At just 1.5 percent, the interest rates probably don’t need to come down any lower in any case. KfW’s function is simply to ensure that funds are made available for deployment by commercial banks, which may not touch an unprofitable venture otherwise.

Papenfuss says KfW is targeting 20,000 to 30,000 systems under its loan program, suggesting a commitment of at least €300 million.

KfW’s aim, according to Axel Nawrath, a member of the KfW Bankengruppe executive board, is to ensure that the output of wind and solar must be “more decoupled” from the grid. Which means that the grid is not necessarily required to accept the output just because the wind happens to be blowing a lot at the time or the sun is shining.

“The success of the energy turnaround will entirely depend on integrating electricity from renewable sources into our energy system on a reliable, permanent basis,” he said in a statement earlier this year.

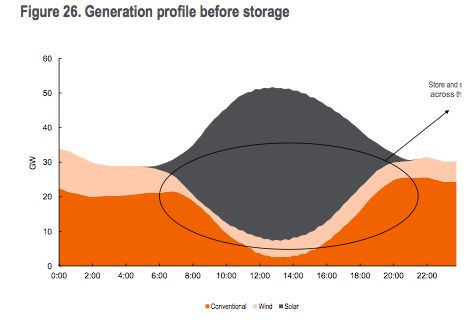

Storage allows the energy output to be held in reserve. The idea is to even out the peaks and troughs, which make it difficult for other generators to stay in business. This is seen as critical as the level of renewable penetration rises to around 40 percent -- a level expected in Germany within the next ten years.

In a perfect world, the output might look something like this graph below, offered by Citi in a recent analysis. It would spread solar and even wind output through the day, and cause fewer headaches for the other plants required to fill in the gaps between the variable output of wind and solar.

According to Papenfuss, households participating in the scheme will spend between €20,000 and €28,000 on solar and storage, depending on the size of the system (the average size is expected to be around 7 kW for the solar array and around 4 kWh for the battery).

The battery component is between €8,000 and €12,000, the grants average around €3,000 (or about 30 percent of the battery cost), and the average loan for the whole system is around €17,000.

The program is not open to systems of more than 30 kW, and nor is it open to solar arrays that were installed before December 31 of last year. They are deemed to have already gotten an economically viable deal via then-active FITs.

Papenfuss says that in order to make sense, battery storage needs to be half of its current cost. This program is designed to set that price drop in motion. He expects the costs to start to fall in 2014; within two years, these systems could be offering a positive return. At that point, he says, the grant component is likely to be withdrawn, although the loan finance program will likely continue.

Over the longer term, KfW hopes that the program will help define standards for use of storage systems. Papenfuss expects storage systems to then focus on wind power and other larger solar systems -- allowing owners to earn a fee for storing energy and releasing it at certain times.

***

Editor's note: This article is reposted in its original form from RenewEconomy. Author credit goes to Giles Parkinson.