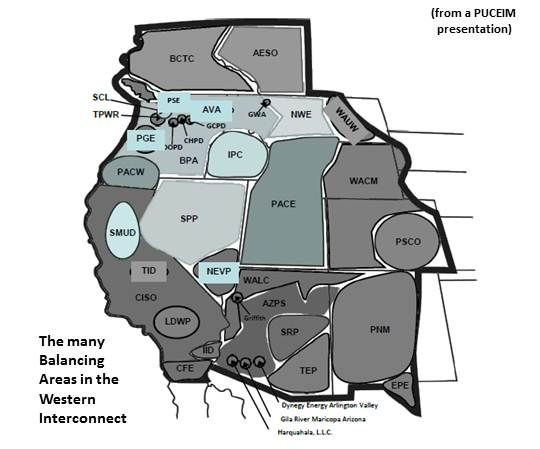

The Western states have 39 or more separate balancing areas in which grid operators control the energy on the system.

When transmission was a matter of moving traditional generation in response to changes in load throughout the Western Interconnect, this balkanized setup was workable. As Load-Serving Entities (LSEs) draw on larger portions of renewables like wind, solar and geothermal energies, managing variability is becoming more complicated.

A Public Utility Commission Energy Imbalance Market (PUCEIM) group composed of researchers from the National Renewable Energy Lab, the Western Governors Association, and multiple independent agencies is working on a plan to pull the Western Interconnect’s disparate areas together into an Energy Imbalance Market (EIM).

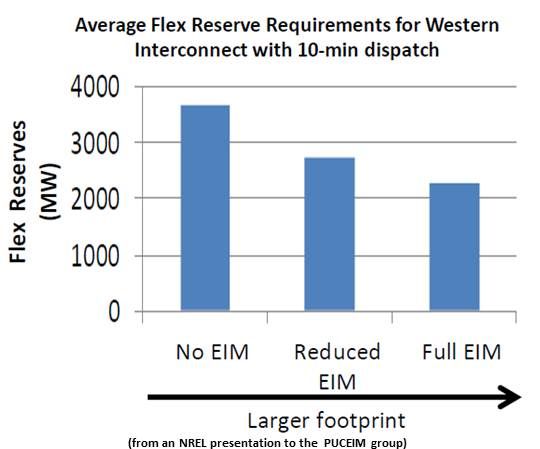

“If you have wider geographic areas sharing different plants, you can smooth some of that variability,” explained Interwest Energy Alliance Southwest Representative Amanda Ormond. “An energy imbalance market allows dispatch of the lowest cost resource to address energy imbalance when a load turns on unexpectedly.”

The West’s many balancing areas are presently relatively inflexible, Ormond said, “because they have only their own reserves to call on for imbalance. They therefore keep large amounts of energy in reserve to meet potential contingencies. And the last generators you turn on are typically the most expensive.”

"This creates economic inefficiencies,” Ormond said. And as more renewables are added across the West, variability will increase and the inefficiencies will become more costly. With an EIM, there is more flexibility.

“If I needed energy in a very short time scale,” Ormond explained, “I could go to the EIM. If energy there is cheaper and if there is transmission to deliver it, I could buy from the market instead of using that last, most expensive, reserve generating capacity.”

An EIM, Ormond explained, would also add vital situational awareness, maximize transmission utilization, and provide sub-hourly markets to address energy imbalances.

Across the west, she said, “there is not a lot of situational awareness in transmission. “In the 2011 San Diego power outage caused by a fault in Arizona, San Diego could not talk to the utilities in Arizona. They literally did not know what was happening.”

While there is transmission congestion in some places, there is drastically underutilized or unused transmission capability elsewhere. “Instead of focusing on the need for new transmission,” Ormond said, “we need to make better use of existing transmission. A lot of that is operational reforms like an EIM.”

At present, Ormond said, “if I need energy, the only opportunity I have to buy is on an hourly basis, at the top of the hour. The EIM would introduce a five-minute market. That adds tremendous flexibility. Being able to buy energy for an imbalance over a five-minute time frame really matches up well with what the needs are.”

To preserve the local autonomy of current balancing areas, Ormond stressed, the EIM is being designed as a voluntary market. “In an EIM, if I am a utility and I have a couple of generators that aren’t running, I could offer them to the system. When someone needs energy, they are going to ask for energy. I can either allow that to be scheduled or not.”

An objection voiced by the American Public Power Association (APPA), a utilities advocate which opposes going forward with an EIM for the Western Interconnect, is that an absence of “critical details” about governance, market monitoring and supervision, and cost raise the concern that an EIM could “quickly evolve into a Regional Transmission Organization (RTO).”

It is a market for balancing energy, Ormond said, not an RTO. Legal opinions suggest “an EIM can have a hard wall to prevent it leading to an RTO. It is a centralized unit for dispatch of balancing energy. It is not for capacity. If you offer a unit, it can be scheduled within the parameters you allow.”

Most importantly, she repeated, it is voluntary. “If I want to go into this market, I can. But if I get into this market and find out it is not cost-effective for me, I can step back out.”

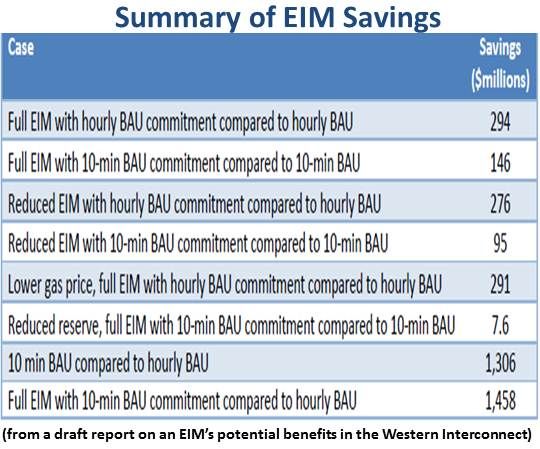

The APPA contends that infrastructure and operating costs “could, in some scenarios, outweigh the estimated benefits, with the net costs potentially reaching $1.25 billion in net present value terms over the first 10 years.”

The PUCEIM group, Ormond said, has preliminary cost estimates from the Southwest Power Pool (SPP) and the California Independent System Operator (CAISO) Corporation, suggesting an estimated $3.50 per-megawatt hour cost but further cost-benefit analyses, along with potential market design studies, are underway.

“The theory is,” Ormond added, “that EIM will improve reliability, but there are no studies yet to bear that out.”