The operation and maintenance of wind farms will be a $10.6 billion business by 2016, according to consulting firm Lucintel. The growth will come, American Wind Energy Association (AWEA) Senior Vice President Stephen Miner said, because by the end of 2011, operating wind projects valued at $40 billion dollars will come out of warranty and require both a financially crucial end-of-warranty inspection and some form of third-party operations and maintenance (O&M) going forward.

The list of companies getting into the O&M business is growing, competition is fervent, the potential reward for better O&M is growing -- and the wind industry, Miner said at AWEA’s January workshop on project performance, expects to add 100,000 more turbines in the next two decades.

In response to the challenge and opportunity, an array of digital technologies are being developed to perform a range of competing and cooperating functions under the general heading of condition monitoring. Electrical engineers’ solutions have made the mechanical engineers’ bigger turbines better. A three-megawatt turbine, according to Chris Henderson of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), is fifteen percent less costly to operate and maintain per megawatt than a one-megawatt turbine.

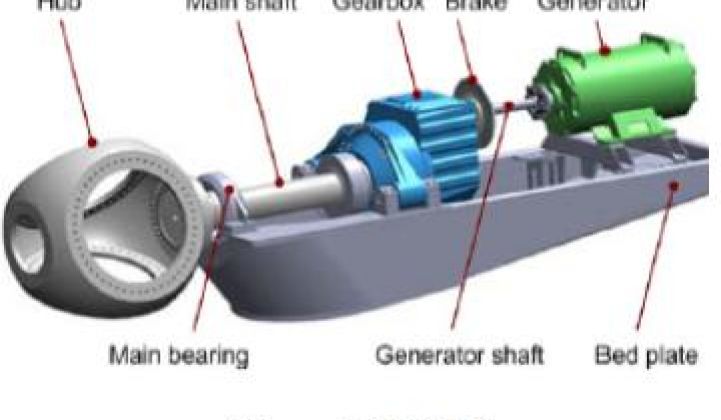

Don Roberts, the Senior Engineer with DNV Renewables, showed the workshop a picture of a gearbox -- the biggest source of turbine operating problems and the source of more than a third of all O&M costs -- and asked how the crack in it could have been avoided or circumvented, “What can you do to limit cost and downtime?” An “expensive uncertainty” is how NREL’s Mark McDade described gearbox problems.

Instrument measurements, oil sample analysis and visual inspections performed by onsite technicians during normal maintenance did not protect the gearbox Roberts exhibited. His solution: remote monitoring of the oil and equipment with sensors that digitally transmit performance data, mining the data derived and comparing it against a growing database for a deeper understanding of performance, using information management methods.

Scott Mackenzie, Natural Power’s Director of Asset Management, described his company’s “total asset management” database and tools that define optimum performance, and Glen Benson, AWS Truepower’s Manager of Performance Analysis, explained his company’s new statistical tools (average wind speed to energy production ratio, downtime to average energy production ratio). Both promise more precise equipment monitoring.

More precise monitoring falls into two broad categories: assessment of the oil and assessment of mechanics. Both assessments can be made by inspection of performance graphs constructed from data collected by embedded sensors and reported digitally either via the turbines’ controllers or directly to offsite wind farm monitoring centers.

Observation of performance in such detail is impossible by visual inspection, standard mechanical gauging and laboratory analysis. “Laboratory oil analysis reports,” according to Roberts, gave “no definitive findings” and technicians did not visually spot incipient trouble. Though “preventive,” in Shermco Industries Compliance Manager Mike Moore’s terminology, visual inspections are not necessarily “predictive.”

Ongoing real-time analysis of oil can be performed by devices such as MetalSCAN, a cantaloupe-sized heavy square metal sensor affixed to a metal tube interposed into the oil’s flow. It reads debris presence as the oil passes through the lubricating hoses attached to it on either side. The ongoing readings convey an assessment that periodic analyses from technician-obtained samples cannot hope to match. Sensors attached to hoses circulating the oil flow in an extra-functional loop can perform a similar analysis.

The vibrations of the machine can also be detected and recorded by sensors. Roberts showed a “vibrational analysis” graph that revealed “multiple harmonics” with a “defect frequency.” He described this method as “extremely effective for early failure detection.”

Following specific bands in the harmonics graph, according to Roberts, is the “most economical tracking” of performance. Integrating identified “alarm data” with SCADA information is the “ideal tracking” of performance. An alarm can be sounded when mined data does not match “statistical data from the project” or “historical baselines” of the equipment.

Vibrational analysis can be done by equipment built into the turbine or by handheld devices like those made by Pruftechnik and SKF. Permanent equipment either from the turbine manufacturer or installed during project development, according to Suzlon Director of Service Engineering Brian Mathis, costs $14,000 to $18,000 per turbine, but provides a “detailed real-time analysis of drive-train components” and “supports predictive maintenance.” $18,000 handheld units carried by technicians are not limited to single turbines, but also do not provide a database of ongoing readings for diagnostic comparisons.

The information obtained and transmitted by sensors from permanent or handheld units is often transmitted to remote operations centers. James Maughan, GE’s General Manager for Product Service, described the capabilities and advantages of a 24/7 remote operations center. With continent-wide reach, a remote center uses IT tools to detect anomalies via detailed data mining and analysis, do remote turbine software upgrades, respond to weather, noise or avian changes or problems within minutes with diagnostics and troubleshooting and, if necessary, can dispatch and confer with on-site technicians.

Statistics from the use of the O&M IT technologies reportedly show them achieving increased and longer-lasting wind farm productivity. Maughan said previously problematic GE gearboxes are showing improved, more robust performance.

Matty Crotty, the CEO of Upwind Solutions, was enthusiastic about the new technologies but, by way of suggesting there are also limitations, quoted an expert in digital data analysis. “Not everything that counts can be counted,” Albert Einstein said, “and not everything that can be counted counts.”