Over the past six months, the U.S. demand response industry has been enveloped in a legal challenge, one that’s threatening to disrupt a decade-old, multi-billion-dollar way of doing business in grid markets around the country.

Or, it could end up being reversed by the Supreme Court -- but not for at least a year.

This is the saga of Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) Order 745, the federal court decision that overturned it in May, the subsequent challenges from power plant operators that could radically expand that decision’s scope, and the resulting grim uncertainty facing the industry this holiday season.

From its genesis as a relatively simple challenge to a federal order, the case has evolved into a pending Supreme Court showdown over the extent to which federal and state regulators can or can’t allow demand -- that is, anything on the customer side of the power meter -- to participate in grid affairs.

“The longer-term future to how demand response -- or more accurately, demand -- participates in the long-term wholesale markets, remains open to discussion.” Stu Bresler, vice president of operations, PJM

The case has pitted demand response providers, grid operators, and state energy regulators in a bitter public-relations war with the Electric Power Supply Association (EPSA), the power generator industry group whose members are leading the lawsuits. It has also opened up a new set of challenges to demand response participation in the capacity markets run by federally regulated grid operators like ISO New England, New York ISO and mid-Atlantic grid operator PJM.

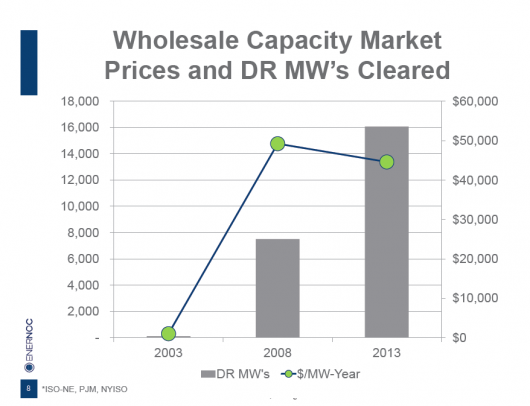

These markets are where the big aggregators like EnerNOC, the company formed by Comverge and Constellation Energy, and NRG Energy acquisition ECS now contribute gigawatts' worth of demand response capacity alongside power generators, and get paid billions of dollars to do it.

Meanwhile, with both sides awaiting a decision from the U.S. Supreme Court on whether or not it will hear the case, grid operators have to do something to mitigate uncertainty around their upcoming capacity auctions this spring, and they’re making contingency plans.

That’s the state of play laid out in a webcast this month, featuring a slugfest between EnerNOC vice president of marketing and sales Gregg Dixon and EPSA president and CEO John Shelk, with PJM vice president of operations Stu Bresler in the role of referee. While Dixon and Shelk traded barbs and contested the costs and benefits of demand response versus power plants, Bresler laid out PJM’s plan for managing the short-term disruptions that could come if the Supreme Court declines to take up the case and May’s decision becomes the law of the land.

Demand versus supply: From small stakes to bigger challenges

Just how far apart the demand response and generator sides are on this issue was made clear in last week’s webcast, hosted by Restructuring Today. “This is a generator cartel,” is how Dixon described the power companies challenging the demand response industry. “If we let them get their way, the result will be billions of dollars in ratepayer costs,” more polluting coal-fired power and a less efficient grid, he said.

Dixon cited independent market monitor reports that have tallied up an estimated $50 billion in reduced customer costs between 2008 and 2013 across the Northeastern and mid-Atlantic grid regions where demand response has taken root most firmly. Because turning down power is cheaper than generating it, demand response has been able to drive down prices for capacity to meet those key summer and wintertime peak loads otherwise served by expensive, seldom-run peaker plants, he said.

Demand response has also been more reliable in recent weather emergencies, like the polar vortex that engulfed much of the northern United States in January, achieving a better than 90 percent reliability rating, versus a 60 rating for the power plants in ISO New England's capacity market, he said.

Shelk responded by calling the “whole 'cartel' thing completely out of bounds,” citing economists, grid operators and FERC commissioners who have called the fairness of Order 745 into question since its inception. More broadly, he questioned whether demand response should be part of the same markets that bring generation supply to the grid: “You can’t sell something you don't own -- you have to buy it first.”

While Shelk conceded that demand response has driven down energy costs, EPSA believes it has done so through unfair market advantages that have robbed the generators of the capital needed to keep critical power plants up and running.

“The reason why many of those plants had operational issues in January was because they’re plants that are slated for retirement," he said. "Why are they slated for retirement? Because the prices for capacity auctions…have been depressed.”

FirstEnergy's challenge to PJM: Roll back demand response

All of these arguments may be a bit confusing, considering that FERC Order 745, and the court decision overturning it, had nothing to do with them. Instead, it affected only the small portion of demand response that plays in federally regulated energy markets.

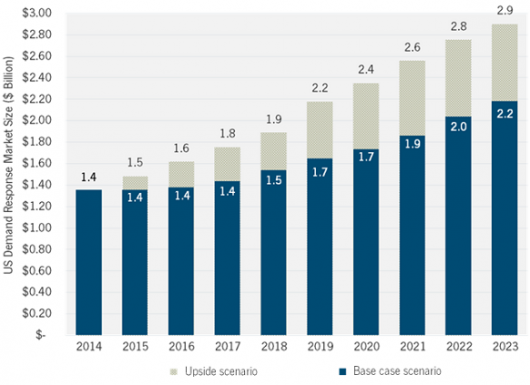

That could reduce cumulative U.S. demand response revenues by $4.4 billion over the next nine years, according to GTM Research's new report, U.S. Demand Response Markets Outlook 2014. That's a significant blow, but not an industry-destroying one.

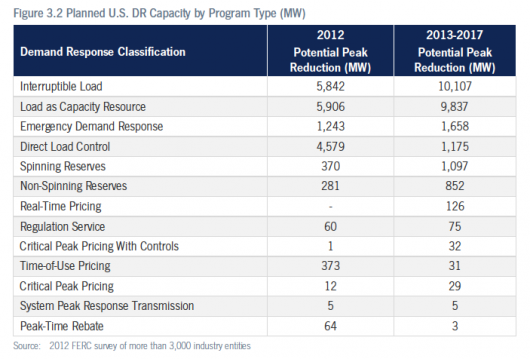

But May’s court ruling has led to broader legal challenges that call into question whether FERC even has the authority to regulate the participation of retail energy customers in wholesale grid markets. On the same day the circuit court panel handed down its decision, Midwest utility FirstEnergy filed a complaint with FERC, demanding that it force PJM to do away with demand-side participation as suppliers of grid capacity -- not just from now on, but also retroactively.

One of FirstEnergy’s demands was for PJM to go back and redo its May 2014 Base Residual Auction to exclude the 11,000 or so megawatts of demand response that won bids for the 2017/2018 season. At an average price of $120 per megawatt-day, that's roughly $1.3 billion in payments that FirstEnergy is demanding to be rolled back.

FirstEnergy cited the circuit court panel’s decision, which stated that the Federal Power Act bars FERC from “directly regulating a matter subject to state control, such as the retail market.” The decision goes on to state that “demand response, while not necessarily a retail sale, is indeed part of the retail market, which, as the statute and case law confirm, is exclusively within the state’s jurisdiction.”

This statement goes beyond the issues central to the argument against FERC Order 745, and has received broad criticism from environmentalists, supporters of energy efficiency, and demand response proponents alike.

As Dixon said, “It shocked everybody that the court would decide on the jurisdictional issue,” given the longstanding precedent of avoiding judicial interference into the arcane workings of a federal agency like FERC. (For more on how the circuit court panel’s decision was shaped by the participation of right-wing D.C. Circuit Court Justice Janice Rogers Brown, read this in-depth report from Grist's David Roberts.)

Shelk called the argument that EPSA and its members want to do away with demand response entirely a “grotesque straw man,” meant to distract from what he insisted are legitimate questions over FERC’s authority. “Some have tried to characterize this quite incorrectly as saying there will be no demand response in the market if this decision is not overturned,” he said. “That is not true.”

At the same time, “investment decisions are being made today whether to retire units, where and how to invest in new reliability, and that affects things for decades,” he said. “This issue of demand response, and who regulates it, has to be seen in that broader context.”

PJM’s contingency plan: The new normal for demand response markets?

The legal situation accelerated earlier this month, when the U.S. Solicitor General’s office announced it would ask the Supreme Court to take up the case on FERC’s behalf. But grid operator PJM has been working on the assumption that this would happen, and making plans for the possible outcomes, for months already, said PJM’s Stu Bresler.

In October, PJM released a white paper that laid out its legal thinking, based on its pressing need to create some market certainty out of what’s largely a legal struggle that is out of its control, Bresler said. EnerNOC condemned the proposal when it came out, and Dixon said last week that he'd prefer for PJM to wait for its stakeholders to get together before issuing any policy proposals.

Bresler responded that "doing nothing" could expose PJM's markets to "one of the most damaging conditions that can overcome our markets: an increasing amount of uncertainty. As more commitments are made under current rules, the uncertainty grows with regards to whether those commitments can be honored in the future,” he said. PJM has to act quickly, since it's set to hold its next capacity auction in May 2015.

The worst-case scenario would be that the Supreme Court declines to take up FERC’s appeal of the Circuit Court’s decision, which could happen in the next few months, he said. If that happens, PJM has proposed a pretty radical new model that it hopes will allow the demand response now participating in its capacity markets to stay in the game, “to be capable of surviving future legal challenges if EPSA stands up as the law of the land."

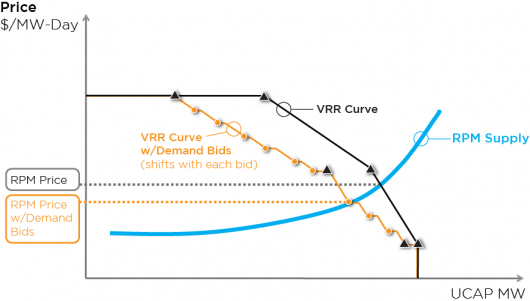

“In essence, we’d look to move demand to the demand side of the equation in the capacity market, very similarly to how price-responsive demand is managed today,” said Bresler. Price-responsive demand (PRD), a form of demand response that's based on time-of-use rates and tariffs, is a subset of programs that makes up a small but growing share of business across multiple grid operator territories.

The mechanics of the new scheme are complex, but PJM goes into some detail in its white paper (PDF), along with supply-demand curve graphs like the one below, for those who know how to read them.

Still, at a high level, there are two key differences between today’s capacity markets and PJM’s proposed system that are hard to see as anything but harmful to demand response aggregators like EnerNOC. First, while demand will get paid capacity-market prices today, they won't get to earn an additional credit when they actually turn down power in the years to come, as happens in today's markets, Bresler said. Instead, customers would count the energy savings they got from using less peak power as their reward -- although the new rates and tariffs put in place to encourage participation in these programs could make that more lucrative than it is today.

Second, participation would be limited to utilities, retail electricity providers and other “load-serving entities" -- and demand-response aggregators don’t have that status today. As GTM Research notes, “In this scenario, pure-play aggregators such as EnerNOC and Comverge would have to negotiate contracts with each individual load-serving entity or risk disappearing.”

Bresler stressed that PJM's proposal to FERC would only come into effect if the Supreme Court rejects the case outright. If it decides to hear the case, PJM will hold off on making any changes until it’s had time to go through its normal stakeholder process, even though “there would still be risk that the Supreme Court would uphold the EPSA decision,” exposing any auctions or payments made between now and then to retroactive risk.

The grid operator is also standing firm on its argument that all of its existing commitments to demand response providers should remain in place -- “Those are clear commitments; they existed prior to the decision,” Bresler said. But if the courts decide otherwise, PJM will seek to build back as many of its commitments as it can through other means, such as contractual relationships between demand response providers and parties with direct relationships to customers.

Meanwhile, power plant groups have filed challenges to demand response's participation in the corresponding capacity programs run by ISO New England and New York ISO. Both have refused to comply, Dixon noted. But if May's decision is upheld, they may be forced to look at their legal options as PJM has.

Dixon stressed that removing the existing capacity markets could lead to blackouts and price spikes, absent a mechanism to allow aggregators like EnerNOC to keep providing what amounts to 80 percent of the region's demand response capacity.

“The concept of portability -- providing that a participant that might not be a load-serving entity can participate in these markets -- is critical,” he said.

What the future holds

While last week's debate between the forces of demand response and power plants offered little sign of reconciliation between the parties, Bresler did note that he heard "at least an indication of agreement in the two presentations that we’ve heard so far." He continued, "Markets need both supply and demand to function. Demand will continue to participate in some way, shape, form or manner in electricity markets."

At the same time, it may not be called "demand response" in the future, he said. “The longer-term future to how demand response -- or more accurately, demand -- participates in the long-term wholesale markets, remains open to discussion."

We've already seen some of these new forms of demand response emerge, including in regions that might have to undergo the wholesale shift in market and program design that PJM is now considering.

Companies like Innovari and Demansys are working on relationships with demand response-providing customers that can be adapted to price-responsive demand type regimes.

Large-scale energy services companies like Schneider Electric, Honeywell and Siemens are also making moves into demand management technology and services, which could be turned over to utilities or managed on behalf of large corporate property portfolios.

Retail utilities like NRG and Constellation could also find opportunities in a legal regime that requires demand response participants to have direct contractual relationships with their individual customers.

Then there are providers of technologies that enable demand response: commercial and industrial load controls from the likes of Enbala or Powerit Solutions, behind-the-meter storage from companies like Stem and Green Charge Networks, smart thermostats from Nest, EcoFactor and EnergyHub, or the technology platforms being rolled out by the likes of Opower, Tendril and AutoGrid.

As GTM Research notes in its recent report, these companies "may find that business opportunities have even increased on the commercial side, as load-serving entities take over some of the capacity hole left by the pure-play aggregators."

Finally, it's important to note that power that may be lost to the federally regulated side of the country's energy markets could well be taken up by individual states. Texas operates a grid system independent of FERC oversight, and states including California and New York are reconfiguring their demand response programs to incorporate more distributed and flexible resources into play.

As the legal questions play out over the coming months and years, we're likely to see much more activity from the states to fill in the gaps, and perhaps to provide the market certainty that's now in limbo at the federal level.