As the U.S. proves to be the among the largest and most stable solar markets, companies from Europe and Asia, as well as new American startups, are opening shop here offering unique value propositions.

However, there are also inherent risks in working with newer entrants, especially when it comes to PV inverter manufacturers. Accurately weighing the benefits versus the risks is a critical role of developers, EPCs, owners, operators, and financiers.

Potential benefits:

- Bigger margins

- Increased yields

- Lower downtime

- More projects that pencil

Potential risks:

- Lack of features/compliance/compatibility

- Increased installation costs

- Inferior performance

- More down time

- Poor service/support

- Other headaches

- Company longevity

Together, these benefits and risks contribute to the total levelized cost of energy (LCOE) over the system’s twenty-plus-year life, and can be grouped into categories that affect:

- The cost-effectiveness of the equipment

- The risk of the equipment and service functioning properly

- The risk of the company surviving for the long term to maintain its service promises

We’ll discuss the cost-effectiveness of the equipment in detail in a future article. In this article, we’ll discuss how to effectively evaluate all the risk factors by providing the right questions to ask a manufacturer, as well as resources on how to get the answers.

Evaluating Equipment and Service Risk: Experience = Quality

While inverters are fairly straightforward to manufacture, it should not be underestimated what can be learned through deploying several gigawatts over the course of decades in various climates and environments. This experience (or lack thereof) affects many things, including but not limited to:

- Component choices

- Incoming and outgoing quality inspection

- Design for extremes, longevity, serviceability and O&M, future-proofing

- Service infrastructure

A simple litmus test to help determine whether a product will live up to its performance claims in the real world is whether the company has completed installations with a large number of partners in various markets over a long period of time. IHS Technology and GTM Research have fairly extensive data regarding this variable.

FIGURE 1: Sungrow was ranked No. 5 in revenue and No. 3 in volume in 2013

The report also mentions “that Chinese-made inverters are gaining increased acceptance in places such as the United States, Germany and the United Kingdom.”

Additionally, inverter manufacturers themselves are reliable sources of data, as long as you know the right questions to ask. Here are some good ones:

- How long has the company been making PV inverters?

- How many gigawatts have been deployed, in how many different climates, environments and countries?

- What data is available on fleet performance?

- What service infrastructure does the company have in place, and what response time can it guarantee?

- What have third parties said about the company?

Taking the answers to these questions together, we can see the company in a more detailed context. For example, Sungrow has deployed more than 7 gigawatts in more than 50 countries since 1997, with below-industry-average failure rates, and has in-house and third-party service technicians and spare parts depots allowing for 24-hour on-site service guarantees in most parts of the U.S. and Canada.

The spread of these installations in several markets over an extended period of time is evidence that the company isn’t just a flash-in-the-pan phenomenon, and that it has adapted to various grid requirements and built service and support infrastructure in several countries.

Outside parties and stakeholders, such as customers and independent engineers, often have the most valuable insight into manufacturers. Be sure to ask for references and independent engineering (IE) reports.

Evaluating Long-Term Risk: Profitability + Strategy = Long-Term Stability

There are currently dozens of PV inverter manufacturers operating in the U.S., and there’s room for maybe five of them to survive. No customer wants to be left with installed inverters but without access to spare parts or service because the manufacturer no longer exists. How does one avoid this?

There are a number of variables to consider, but profitability and global diversification are particularly important.

To assess profitability, financial statements can often be found online. If not, you can ask the company for a copy directly. Once in hand, net revenue and net debt are perhaps the most telling indicators.

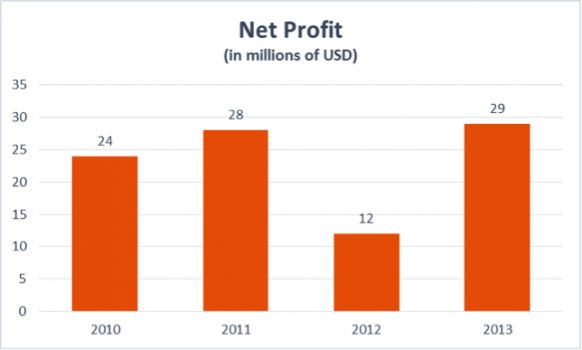

FIGURE 2: Sungrow is one of the few pure-play inverter manufacturers to be consistently profitable

Additionally, here are a few more good questions to ask:

- Is the company currently profitable?

- In the case of conglomerates, is the PV inverter division profitable?

- If not, what is the company's plan to reach profitability, especially in light of decreasing incentives and margins?

- In which markets is the company profitable?

- In which markets is the company growing?

Global diversification is especially important in solar, as regional markets come and go quickly. For example, a company based in a market that is insulated from international competition and where incentives and margins are high may be profitable (for example, in Japan). But when the incentives dry up, as all must eventually, is the company positioned to survive? Are the profits in the firm's home market subsidizing the international business as it tries to buy market share?

GTM Research took up the topic of global competitiveness in its 2013 Global PV Inverter Landscape report. The 225-page report evaluates 78 different inverter manufacturers, and ranks Sungrow the fourth most competitively positioned firm.

An important note on PV inverter manufacturers that are a part of conglomerates: it is important to analyze the inverter business unit separately from the conglomerate. There have been plenty of conglomerates that have left the solar space in the U.S. due to lack of profitability, leaving customers with stranded products without spare parts, service or warranties.

Conclusion

In summary, when evaluating risk of new PV inverter entrants to the U.S. market, it is important to measure product and service risk, as well as long-term viability risk. Product and service risk can easily be measured by looking at experience. Long-term viability risk can be measured by looking at profitability, net debt and global diversification. Knowing where to look for this information -- and the specific questions to ask manufacturers to uncover the larger narrative behind the numbers -- helps simplify this task.