How can a startup tackle large, lucrative projects when it lacks the hundreds of millions of dollars in capital and credit needed to turn them into reality?

Stick to the drawing board.

Gridflex Energy is trying to make a name for itself in energy storage by serving as an “originator.” It scours the U.S. for suitable locations for multi-megawatt pumped hydro or compressed facilities, studies the geological, demographic, infrastructure and other issues prevailing at the site, and then draws up a proposal, according to CEO Matt Shapiro. Transmission access, wind or solar capacity, population density, and a wealth of other factors need to be considered.

Interestingly, peak power is often not that important in the overall evaluation.

“Arbitrage only works in Southern California,” he said. “Most of the time that off peak/peak delta isn’t large enough.”

Ideally, an energy developer or utility with funds and the ability to seek DOE loans will then take the next step by adopting the project as its own. Thus, Gridflex isn’t a developer, but seems to take projects past the conceptual stage an incubator might. Maybe think of them as Executive Producer.

It recently mapped out four projects in Wyoming that could provide 1.9 gigawatts of dispatchable energy for wind or solar farms. It also has strategies for facilities in Nevada, Arizona, West Virginia, Oregon and Washington. (Note: storage vendors often rate their technologies in terms of capacity first -- megawatts and kilowatts -- and potential output, i.e., megawatt-hours, second.)

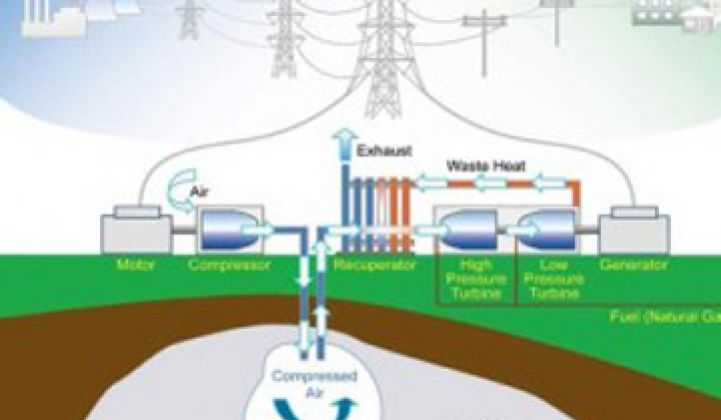

All of the above are pumped hydro projects, which costs around $1,500 a kilowatt. The firm also has plans for two compressed air energy storage facilities.

“CAES [compressed air energy storage] can be less expensive in certain areas,” said Shapiro.

One of the more unusual projects is a 300-megawatt pumped storage facility in Hawaii. In pumped hydro storage facilities, energy is produced by allowing water from an upper reservoir pass through a turbine on its way to a lower reservoir. In the Hawaii proposal, the ocean (no capital required) would serve as the lower reservoir.

“Civil engineering is the biggest cost of pumped hydro,” he said.

Oahu plans to get 500 megawatts of the 1200 megawatt capacity it needs from renewables, particularly wind and solar. To balance the loads coming from these sources, some have proposed using the diesel generators. Storage, assuming the environmental issues could be managed, would be cleaner, Shapiro argued.

"We can create firm capacity that is mostly renewable," he said. "The incremental cost (for additional megawatts) is surprisingly low."

Storage has been the Holy Grail of the green industry for the last few years. Some companies such as Beacon Power and AES have begun to deliver storage-as-a-service packages to utilities with, respectively, flywheels and banks of lithium-ion batteries. Flywheels and batteries, however, are typically used to balance power. They are not used to store large amounts of energy for long periods of time.

Mega storage is a whole different ball game. The market is potentially huge -- California passed legislation outlining incentives and mandates for utility-scale storage,

The technology has been around for years and Gridflex says it is not introducing new devices like the modular compressed air tanks proposed by companies like SustainX. This is classic WPA-like big engineering. A 110-megawatt compressed air storage facility has been in operation in Alabama since 1978. Even in an ideal situation, a project might take seven or more years from concept to completion.

Unlike batteries, compressed air and pumped hydro generally aren’t modular either. Terrain -- the size of the underground aquifer, the volume of the reservoir, etc. -- plays a dominant factor. Whether the facilities need to be qualified as utilities under FERC or other regulations is also a consideration.