Solar installations were removed from twenty-four San Diego Unified School District campuses after corrosion was discovered that threatened the possibility of electrical issues that could lead to fires.

The 4.3-megawatt installation was built in 2005-06 by Solar Integrated Technologies (SIT). SIT was acquired by Energy Conversion Devices (ECD) (PINK:ENERQ) in 2009. ECD’s Uni-Solar manufactured the panels. SIT built the integrated solar-electric systems made up of Uni-Solar PV panels and Sarnafil roofing material.

Both ECD and SIT filed for bankruptcy earlier this year.

The panels were installed through a third-party ownership (TPO) financing agreement in which the school district made no upfront investment. SIT had responsibility for operations and maintenance. GE Financial Services (NYSE: GE) was the twenty-year lessor.

Due to the other parties’ bankruptcies, GE Financial Services took on the removal of the solar systems, at its own cost, though it had no legal obligation to do so. The only loss to the school district was the promised electricity bill savings.

It has been reported that a manufacturing defect in the panels allowed water seepage, corrosion and the potential for fire-inducing short circuits. “Workers have not yet reached a final conclusion as to the exact cause of the problem, and it would not be prudent to speculate,” GE spokesperson Christa Bowers told GTM.

This is a wakeup call for the solar industry. It explains DuPont’s recent initiative, in partnership with solar developer Distributed Sun (D-Sun), which finances, constructs, owns and operates PV power plants, to establish specifications for module materials that will “raise awareness of the importance of durability and reliability” of panels in the bankability of solar projects.

And it explains why DuPont Innovalight General Manger-Founder Conrad Burke is crusading for more quality control in module materials.

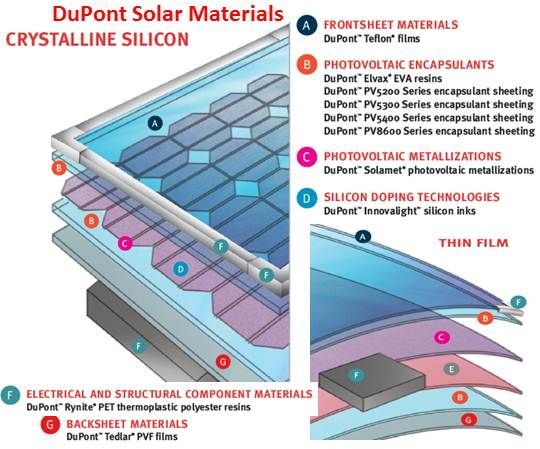

DuPont's (NYSE:DD) 2011 $1.4 billion in sales to the solar industry makes it one of the world’s biggest suppliers of panel and parts materials such as metallization pastes, resins, encapsulants, back-sheet materials, thin film substrates, silicon inks, vacuum seals and junction box structural materials. “Half of the approximately 300 million solar panels that have been installed around the world over the last 35 years have some kind of DuPont materials,” Burke said.

Low-cost modules and a rising tide of funding for TPO financing have fueled an unprecedented solar expansion in the last two years, but there is growing concern about the loss of quality.

The bankability of solar installations will come into question if major funders find themselves saddled like GE Financial Services did with the San Diego incident. Without their capital, financing would be harder to obtain and solar would be more expensive.

Yet intense competition among module manufacturers is driving them toward cheaper, less reliable materials, according to Burke. “There is a race for survival. Corners are being cut.” Some manufacturers are losing sight of the fact that “if you can make a solar panel last longer, your financial returns and your investment returns improve and materials matter a great deal in that.”

Burke foresees a $100 billion solar industry within a few years, but says that “between where we are today and getting to that point, I think we’re going to have some bumpiness.” Industry consultant SolarBuyer LLC, he explained, predicts that more compromised projects, like the one in San Diego, will emerge. “Consumers are going to benefit from cheaper solar panels and we’re all for that here at DuPont because it will make solar more affordable. But quality, reliability and performance should not be compromised.”

Once a design defect is eliminated, there are three kinds of testing of materials in “an integrated, quality focused procurement process,” explained PV Evolution Laboratories CEO Jenya Meydbray, who now does independent solar product testing after running SunPower’s supplier qualification program for five years. Meydbray wants to see the industry adopt practices like “upfront, long-term testing to evaluate the product, factory audits while the products are being manufactured, and spot checks of the product when it hits the ground at the project site.”

“We have statistical models,” Meydbray continued, “that define the conclusions you can make based on testing. If your bank wants you to be 95 percent positive that your products are defect-free, that means you have to test a specific amount, statistically. If your risk tolerance is a little bit looser, and your budget is a little smaller, maybe you can get away with an 80 percent confidence level.”

What happened in San Diego, he speculated, was “probably a combination of [problems with] workmanship, quality control, and materials.”

These are “early days,” Meydbray said, “in an incredibly competitive space where nobody is making profit. There is mass consolidation. People will have massive solar fleets where the warranty is worthless because the manufacturer doesn’t exist anymore. That will impact the residual value of plants, when they start changing hands.”

There are, he said, “a lot poor systems and negative investor returns from poor quality things going out there.”

He remains a staunch solar advocate, Meydbray said. “There are a lot of excellent performing systems and excellent products out there. But the reality of today’s market is you have to rely on what you’re buying, not who you’re buying it from.”