Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology said Wednesday that they have invented a technology that could boost a solar panel's efficiency by up to 50 percent and are about to spin off a company around it.

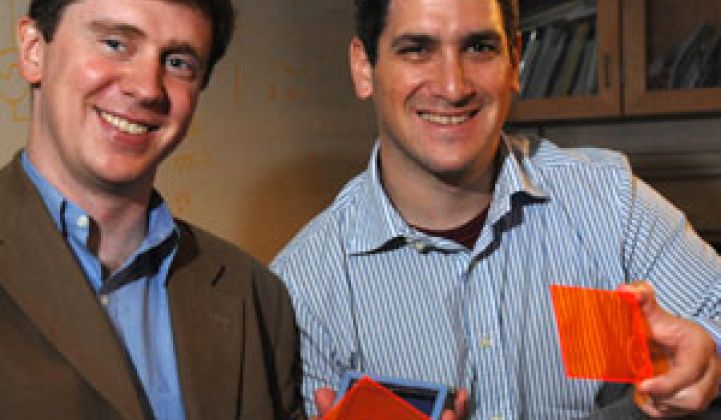

Three members of the research team, which is publishing its findings in Friday's edition of Science, are in the process of incorporating a startup called Covalent Solar to develop the technology.

The team has spent two years identifying organic dyes, painted onto glass or plastic, that can effectively concentrate the sun’s light onto solar cells, enabling them to produce more electricity from fewer cells.

The dyes basically reflect the light (technically, it’s actually absorbed and then sent back out), so that some of it is trapped inside the plane of glass, said Jon Mapel, a member of the research team.

With the help of a scientific principal called "internal refraction," which is the same principal that keeps light trapped in optical fibers, the light bounces to the edges of the glass, which have been equipped with strips of solar cells that convert it into electricity.

Integrated into solar panels available today, the technology could potentially boost the amount of light the panels convert into electricity by as much as 50 percent, Mapel said.

He said the approach would cost less than adding 50 percent more panels, so consumers would get more electricity for their money, but didn’t disclose any further information about cost.

Also, unlike most photovoltaic concentrators, such as those being developed by Concentrix Solar, SolFocus, Sunrgi and Soliant Energy, these concentrators look like flat panels and wouldn’t require extra parts to track the sun, he said.

The company hopes the technology could be used for both rooftop systems, such as the concentrators that Soliant and Sunrgi are developing, and for large solar farms, such as the concentrators that Concentrix and SolFocus are developing.

Mapel also thinks the technology could one day be integrated into windows, where a grayish tint would let in 20 percent to 30 percent of the outside light, while simultaneously directing the light toward solar cells around the window's edges.

Covalent Solar expects to bring its first product to market in three years, he said.

But taking technology from the lab to the market can be a daunting task, and Covalent still has many challenges to work out.

According to the research the team is publishing in Science, the technology only increased a thin-film panels’ efficiency by 20 percent in tests.

And without being paired with a panel, the coated glass only converted 6.8 percent of the light that hit the surface of the concentrator.

Another problem is that one of the dyes used in the study has demonstrated a life span of about 10 years.

Come rain, snow or unrelenting heat, a solar system has to be able to handle all that nature can throw at it – at least for as long as the warranty lasts. Most of today’s solar panels come with 20- to 25-year warranties.

So one of Covalent’s challenges will be to identify dyes that have longer lifespans and can still boost efficiency.

Another challenge will be to demonstrate that the technology can live up to the solar industry's expectations, Mapel said, and that means figuring out more mundane things like the proper encapsulation and packaging of their technology.

To do all this, Covalent will need money. So far, the business is running on about $30,000 it won from an MIT business competition earlier this year. Mapel said Covalent would be seeking either venture capital or corporate funding in the coming months.

Mapel and his fellow researchers aren't the first to experiment with dyes and optics as a way to concentrate solar.

In the 1970s, academic researchers along with big-name companies like Exxon were developing similar concentrators. At the time, those working with the technology were struggling to increase the amount of light to reach the edges of glass and plastics.

"After the energy crisis in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s a lot of research in solar stopped," Mapel said, explaining that as a result many of those using dyes as concentrators shelved their work.

But a resurgence in renewable energy has sparked a greater interest in how to make solar more efficient and cheaper.

Researchers at the Energy Research Centre of the Netherlands and the Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems are also exploring dyes for solar-concentrating technology.

Get the scoop on solar finance at our seminar at Intersolar North America on July 16, 2008 in San Francisco. Click here to register or for more details.