Bloom Energy, the deep-pocketed startup that’s garnered more than $400 million of the $1.4 billion given out by California’s Self-Generation Incentive Program, could soon see its fuel cells barred from the program entirely -- both because they emit too much CO2, and because they cost more than they're worth compared to the alternative technologies.

That’s the harsh assessment from a November report (PDF) from Energy Division staff at the California Public Utilities Commission. Issued just days after the commission’s controversial decision to allow the startup’s fuel cells to just barely squeak in under new Self-Generation Incentive Program (SGIP) greenhouse gas emissions limits, the staff paper suggests new rules that could put an end to the deep-pocketed Silicon Valley startup’s participation in the landmark incentive program.

These recommendations, submitted as part of a review of the program ordered by state law SB 861, are still merely in the process of being considered for inclusion in a CPUC proposed decision, and are subject to revision. Bloom Energy is protesting them, saying that they’re based on outdated and inaccurate data on the efficiency, CO2 footprint and cost of its fuel cells versus other SGIP-eligible systems, such as behind-the-meter energy storage and on-site combined heat and power (CHP) systems.

But the staff report is backed by environmental groups, renewable energy providers and energy storage advocates who say that Bloom should no longer have a place in a program meant to incentivize emerging, low-carbon distributed energy technologies.

“We want to put the money where we get the most value, and that’s not an electric-only fuel cell,” Matthew Vespa, senior attorney at the Sierra Club, one of the most vocal foes of Bloom’s participation in the program, said in a Tuesday interview. “Their product is expensive, and it has really high greenhouse gas emissions.” Under the new staff proposal, “I don’t see how it gets public funding -- and I don’t see how it survives without it.”

How GHG limits and cost-benefit tests could weigh against Bloom

The CPUC staff analysis looks at two specific aspects of Bloom Energy’s fuel cells that it says could disqualify it from SGIP participation. The first is their greenhouse gas (GHG) impact, which is being reviewed under the state mandate that any SGIP-eligible technology should lead to lower greenhouse gas emissions compared to the business-as-usual scenario.

On this point, the staff report notes that Bloom’s fuel cells have a 10-year average emission rate of 351 kilograms per megawatt-hour -- just barely over the 350 kilograms per megawatt-hour maximum set by November’s decision. “By a small margin, then, it appears that the current generation of fuel-cell technology fails to meet the GHG requirements of the decision on GHG factor updates,” the report states.

That’s a striking reversal from the CPUC’s November decision (PDF), which lowered the emissions eligibility ceiling to 334 kilograms of CO2 per megawatt-hour in 2016 -- just barely allowing Bloom’s first-year average emissions figure of 333.4 kilograms of CO2 per megawatt-hour to make the cut.

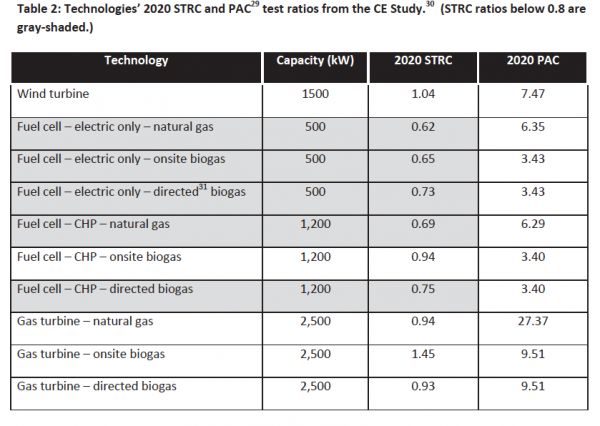

The second measure is a cost-benefit measurement known as a “Societal Total Resource Cost,” or STRC, test. This isn’t required under state law or current SGIP rules, but the staff report lists it as one of two “preferences, or ‘soft’ requirements,” that could be considered for inclusion in the program under further CPUC modifications.

“On November 23, Energy Division and the SGIP PAs” -- the program administrators, also known as the investor-owned utilities that disburse program funds -- “released the 2015 SGIP Cost-Effectiveness Study,” the report noted. Authored by Itron, the study “applies a filter to technologies based on how they are expected to perform on the STRC in the year 2020.”

That analysis yields an STRC cost-benefit ratio for each technology, with anything below 1.0 deemed not cost-effective. The staff report allows for some leeway in that cutoff point, noting Itron’s recommendation that “uncertainty about future costs and market trends makes it prudent to lower the threshold to 0.8.”

Even so, as the chart below indicates, Bloom’s electric-only fuel cells don’t meet that 0.8 ratio requirement, whether they’re being fueled by natural gas, on-site biogas, or “directed” biogas from a contracted party.

Summing up these two points, the staff reports finds that “in terms of GHG, natural-gas-consuming pure electric fuel cells fail, by a small margin, to be cleaner than the grid.” It goes on to state that “it is expected that by 2020 the total societal costs of fuel cells and natural-gas- and directed-biogas-fired microturbines will greatly exceed their benefits -- fuel cells because of high capital costs, and microturbines because of low operating efficiencies.”

“Based on these observations, staff recommends that SGIP funding no longer be provided for natural-gas-fueled pure electric fuel cells, or for natural-gas-fired microturbines,” the report concludes.

The critiques and defenses of Bloom’s technology

We’ve seen plentiful comments from other parties that back up the staff report’s findings. In comments filed in January (PDF), rooftop solar and behind-the-meter energy storage provider SolarCity stated, “Given the increasing role of zero-emission renewable resources in the state’s energy portfolio, it is vitally important that the commission ensure that SGIP technologies are no dirtier than what would otherwise be sourced from the grid. Additionally, given limited program funding, it is equally important that the commission not deploy ratepayer monies toward technologies that fail to meet a reasonable cost-effectiveness threshold.”

Alex Morris, director of policy and regulatory affairs for the California Energy Storage Association, which supports the staff proposal, noted in an email that “given that SGIP projects operate 10 or more years into the future, the program eligibility should ensure the grid's greenhouse gas reduction goals are met. That may require removing some technology groups, which can be tough. The Staff Proposal lays out clear principles and metrics to guide these tough eligibility and funding-allocation decisions.”

Bloom Energy’s filings with the CPUC lay out a multifaceted defense of its technology against the staff report’s findings. In a Tuesday email, Asim Hussain, vice president of marketing and customer experience for Bloom Energy, emailed the following statement in response to questions about the CPUC staff proposal’s greenhouse gas metrics:

“Bloom more than meets the new GHG standards set by the CPUC and meets all other SGIP eligibility requirements. The fact is that Bloom’s latest Energy Servers deliver initial efficiencies over 65%, and easily improve upon the new SGIP standard of 350 kg per MWh. The initial staff proposal is inaccurate since it used backward-looking data rather than the appropriate data reflecting the current generation of our energy server that would be the basis for any new SGIP awards. ”

As for the staff report’s findings on Societal Total Resource Cost, Bloom states in a January filing (PDF) that this metric “should not be used to determine eligibility,” as it “contains too many uncertainties and inaccuracies.” Because of this uncertainty, “conclusions drawn from model results should not be used as the basis for decisions until such time that the model is updated and verified.”

To back this up, Bloom cites its own analysis, using adjusted first-year efficiency and annual degradation factors that it says are more accurate than those used by the staff report, which yields an STRC cost-benefit ratio of 0.77, much closer to the 0.8 cutoff set for eligibility. It also points out that the staff report’s calculation uses natural-gas prices from years past, rather than much lower current-day prices -- a problem, given that those prices make up “the largest component of the costs for natural gas all-electric fuel cells in the STRC test.”

Not all of the comments in the SGIP proceeding disagree with Bloom’s assessments, at least not in their entirety. The Center for Sustainable Energy (CSE), a nonprofit group that is also an SGIP program administrator on behalf of San Diego Gas & Electric, wrote in a January filing (PDF) that it “wholeheartedly agrees with Bloom that a data-driven approach” should guide the CPUC’s choices in terms of specific technologies, and that the STRC test may lack the accuracy to make those assessments.

On the other hand, “we disagree that we should simply assume that new technologies meet program goals,” the group wrote. To deal with this, CSE suggests that “before the commission issues a decision on technology eligibility, the manufacturers and developers of technologies under consideration for removal from the SGIP submit relevant data to the commission showing that they meet all program requirements in question.”

It’s not yet clear how the staff report’s recommendations, Bloom’s objections, and other parties’ views will be taken up by the CPUC. “A Proposed Decision is being prepared to implement SB 861 and make other program modifications related to the proposals in the Staff Proposal and subsequent party comments,” CPUC spokesperson Terrie Prosper wrote in a Tuesday email. But the timeframe for releasing that proposed decision has yet to be set, she wrote.

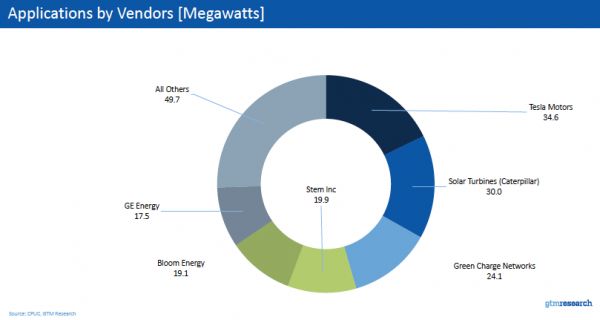

Meanwhile, Bloom hasn’t slowed down in applying for SGIP money for new projects. In the most recent round of applications for funding for the first half of 2016 -- a process that some vendors have complained was gamed by other participants -- the company submitted 38 applications for a combined 19.1 megawatts of projects, according to data compiled by GTM Research.