Is there really much of a difference between demand response and smart grid?

Demand response companies try to curb peak power and are increasingly moving toward managing power throughout the day to reduce energy consumption. Smart grid companies want to add intelligence to the grid so that one day they can shut down clothes dryers and curb air conditioners remotely, sort of like demand response companies.

The main difference seems to be that they live in parallel, alternative universes. Utilities want to own the smart grid and they outsource demand response functions to companies like EnerNoc, Comverge and CPower.

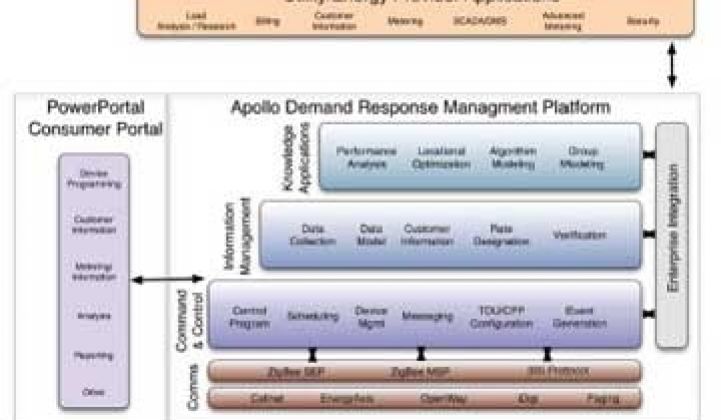

Smoothing over the gap will be one of Comverge's primary goals in the coming year. The company's Apollo platform effectively serves as a glue to allow operators to dig out data and control equipment in the field much easier. A utility in Pennsylvania has already agreed to adopt it.

It will also better connect demand response functions with things like billing systems, said new CEO Blake Young. Young will go over Apollo in more detail at DistribuTech next week.

"The amount of data that will come out of the smart grid will be exponential," he said in an interview. "The shift to smart grid is not going to be like The Wizard of Oz. You just don't click your heels and go home."

In the process, of course, Comverge wants to become more ensconced in the day-to-day operations of utilities instead of just a hired hand during peak events. By moving into management, the company begins to encroach on territory staked out by companies like eMeter, Oracle and others, which in turn want to move into Comverge's ancestral home.

A key selling point will be familiarity. Comverge is over 12 years old and manages over 3 gigawatts of capacity. Roughly half of the demand response business revolves around residences.

How will the smart grid evolve? Intelligent, consumer-controlled thermostats and energy panels will play a role, but autonomic systems that control heaters and air conditioners that effectively let consumers forget about their thermostats will probably be more common, he said.

"We are a long way from the consumer component leading the pack," he said.

Common standards for communications protocols will likely emerge -- ZigBee and the Wi-Fi alliance agreed to cooperate this week, ending their war of words -- but a lot of the underlying hardware systems will remain unique. That's good for vendors, but it means consolidation may occur slower than some expect.

The ultimate smart grid network, meanwhile, may become a hybrid. Utilities can save money by carrying traffic on public cellular networks, but quality of service issues and other factors will continue to make owning their own networks attractive. Still, it would be difficult for any utility to cover the capital expense of a complete, dedicated network. Thus, expect to see carrier alliances, he said.

Finally, smart grid companies will have to get used to the pace of the industry.

"It's no secret that utilities can pilot themselves to death," he said.