Community solar is the idea that people who don’t happen to have rooftops suited for solar panels ought to be able to invest in, and reap the rewards of, solar panels someplace else.

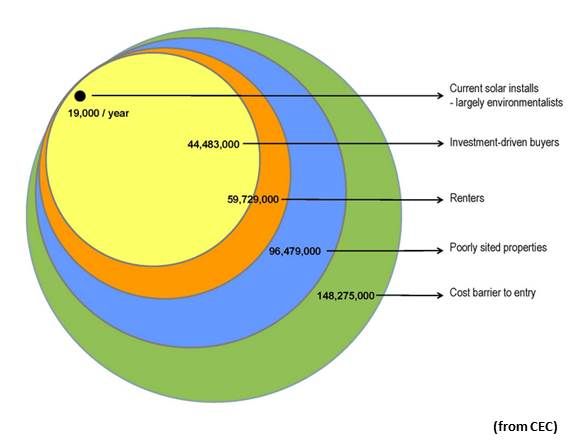

It’s a tempting concept, because it could give the roughly three-quarters of Americans who don’t have solar-friendly rooftops (renters, low power users, forest dwellers, etc.) a way to buy into the distributed solar game.

But behind the vaguely defined concept lies a complex world of power-purchase agreements, limited private partnerships, special purpose entities, nonprofits and cooperatives, and other means to a common end. Each state has its own laws and regulations, and each utility has its own interests that could make it a partner with, or opponent to, community solar.

That makes for a confusing and still-forming market for developers, financiers and solar technology providers to parse out. At this week’s Intersolar conference in San Francisco, Paul Spencer, CEO of Clean Energy Collective (CEC), helped provide some context with the latest figures on community solar projects and business models around the country.

Carbondale, Colo.-based CEC has enabled $70 million in investment across 29 solar projects in eight states based on its own special purpose entity (SPE) form of community solar. CEC uses what it calls “virtual net metering” to make sure each investor/owner household treats its virtual stake in one of its solar farms as if it’s on its roof -- in other words, no extra credits for oversized systems.

CEC’s approach differs slightly from Oakland, Calif.-based Mosaic Solar’s crowdfunding model, which allows neighbors to finance and receive financial reward from new projects. That, in turn, differs from SolarCity acquisition Common Assets, which runs a platform to allow people and organizations to invest in solar-based financial products.

But the vast majority of the 80 or so projects across ten states pursuing a community solar model are one-off projects, often using grants to pencil out, Spencer said. “We need more providers than that to make this a viable solution,” he added -- of the handful of solar project developers doing community solar he's aware of, only two have done more than one project. (UPDATE: In comments below, readers point out that there are several other developers such as SunShare and Ecoplexus, doing multiple projects in states like Colorado.)

Community solar also needs real-world-tested business models that stand up to legal and regulatory scrutiny, he said. Each model comes with its own benefits, and its own drawbacks, on this front. Customer-owned cooperatives or nonprofits are simpler to set up, but they lack access to federal Investment Tax Credit revenues, for example.

Limited liability corporation structures offer access to tax credits, but must adhere to consumer protection and securities law that limits how many non-millionaires can participate. Utility or developer-owned projects that are leased by customers are “the easiest way to do it,” he said, but “they also have a tremendously lower value proposition to the consumer, because the consumer doesn’t own the value of the asset.”

How participants are paid off also varies from state to state and by utility, with on-bill credits, renewable energy credits or net-metering-based arrangements possibilities, he said. More than two-thirds of the projects CEC has set up for utilities involves a straight power-purchase agreement that required no special legislation to enable, he noted.

CEC spent a “couple million dollars” and about eighteen months working out its own approach, which builds a private entity to manage the project. That’s no small deal, and involves things like integrating with utility customer billing systems and carrying the insurance to guarantee maintenance over the project’s lifetime.

But at the end of the road could lie a model that’s replicable from state to state. In its exhaustive community solar report (PDF), the Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory noted that, “while the CEC incurred significant legal costs to set up the company structure, they are now able to offer participation to an unlimited number of utility customers.”

Spencer defined the addressable market as about 1,000 of the largest utilities in the country, adding up to 134 million metered endpoints. “We’re able to address 100 percent of those metered customers -- about twenty times the number of customers we can get excited about sharing the benefits of solar than we’ve got available today.”

That comparison is to the market opportunity for third-party solar players like SolarCity, Sunrun, Sungevity, SunPower, Vivint and a growing list of competitors, he explained. According to his math, the third-party financing models are limited to roughly 15 percent of an addressable market of some 45 million customers in the sixteen states in which they’re allowed. That adds up to about 6.7 million customers with the right rooftop in the right climate at the right price, and “that’s a very small percentage of the ratepayers in the United States.”

Community solar could also help utilities get in front of the rise of customer-owned solar, if they can find the right combination of short-term incentives and long-term rewards to get customers to sign up, he noted. Utilities can get solar power for their renewable portfolio standard goals in some cases, as well as a long-term generation source that’s insulated from changes in the price of natural gas or coal.

“Community solar can’t compete with large-scale, utility-scale solar on price per watt, but we can be cost-competitive against retail rates,” said Spencer. This plays into how utilities calculate how much they’re willing to spend in incentives or special rate plans to get customers to sign up. Some benefits are needed, because green power-purchase programs that ask people to pay more for going green don’t work.

But with the right balance of utility and customer benefits, community solar can establish a long-term customer relationship around a shared solar asset, he noted. In a world where utility customers may soon be able to generate and store their own solar power, and companies like SolarCity and NRG Energy are laying plans to help them do it, that could be the greatest value of all.