This week, California utility regulators issued a long-awaited proposal to reform the complex, multi-tiered rate structures for residential customers of the state’s big three investor-owned utilities. And as solar advocates expected, it contains some good news and some bad news for the economics of customer-owned net-metered solar PV systems.

At the same time, the proposed decision from the California Public Utilities Commission (PDF) leaves open some big questions on how future rate design decisions will affect solar economics. These pending issues include coming changes to the state’s net metering policy, and how new time-of-use rates might incentivize customers to alter their energy use to support a more renewables-rich grid.

As Shayle Kann, senior vice president of research for Greentech Media, noted, “the CPUC is still considering options for a successor net energy metering program, which could have a bigger impact on the solar value proposition than these rate structure revisions. With that said, this proposal goes both ways for solar.”

How flattening tiers could undercut solar payback assumptions

Tuesday’s decision comes two years after the passage of AB 327, a law that put into motion many different changes to state energy policy. AB 327 was initially opposed by solar and environmental groups, because it would allow utilities to do two things that could reduce the economic benefits of investing in solar or energy efficiency.

The first change would reduce the four-tier structure that charges customers a lot more per kilowatt-hour as they use more power over the course of a month. Those rates now range dramatically, from about 13 cents per kilowatt-hour for the lowest tiers, to as high as 42 cents per kilowatt-hour for consumption in the highest tiers.

Tuesday’s proposed decision calls for shifting to a two-tier monthly rate structure, with much less stark price differences between the two, over the next three years. That could hurt the economics of net metering, which pays customers back for the solar power they generate at retail rates. In simple terms, the higher a customer's typical monthly bill, the more valuable rooftop solar is in reducing it, particularly at the high-tier margins.

Collapsing the state's four-tier system into two tiers could also have significant implications for third-party solar providers like SolarCity and Sunrun. These companies have signed up a number of high-energy-consuming households and calculated their long-term net metering paybacks based on the existing rates.

It's unclear how flattening rate structures will affect these companies' long-range financial projections. SolarCity CFO Bob Kelly told analysts in a July 2013 conference call that shifting to a two-tier structure shouldn't have too much of an effect on the company's business model. But The Alliance for Solar Choice (TASC), a solar industry group, said in a Thursday statement (PDF) that the CPUC's proposed decision would allow the state's big utilities to fairly rapidly phase out the high-priced top tier rates in a way that could "pose a challenge for the solar industry."

At the same time, “the tier-flattening portion was largely expected and also goes both ways,” GTM’s Kann said. “It erodes solar project economics for high-energy users, but potentially opens up the market for low-energy users that previously couldn't see savings from solar.”

Time-of-use rates: Changing the equation on rooftop solar ROI

The benefits for lower-energy-consuming customers could become even more apparent as California’s utilities create time-of-use (TOU) rates for their residential customers -- and under Tuesday’s proposed decision, those TOU rates will be coming by the end of the decade. The decision orders Pacific Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison and San Diego Gas & Electric to start TOU pilots by next year, and to file proposals by the end of 2017 to move to a “default TOU rate structure to begin in 2019.”

Unlike monthly tiered prices, which don’t correspond to the cost of grid power, time-of-use rates create a direct linkage between the cost of generating electricity and the prices customers pay. Energy use spikes during hot summer afternoons, when air conditioners across the state are running full blast, and during late evenings in spring and fall, when people come home from work and power up their household lights, appliances and electronics. Utilities have to ramp up expensive marginal generation units to meet those peaks in demand, pushing wholesale prices far higher than their overnight lows.

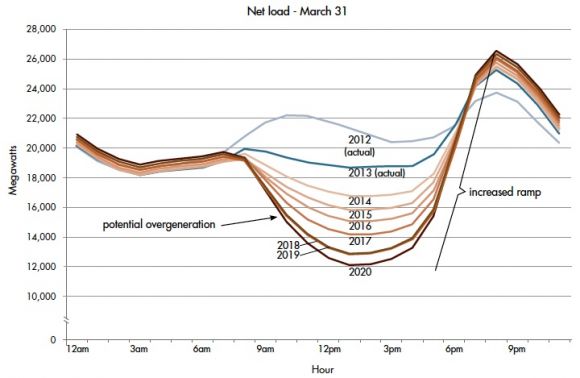

Well-designed time-of-use pricing regimes are also “key to helping customers better align their use of energy to when we’ve got more clean energy on the grid,” James Fine, senior economist with the Environmental Defense Fund, said in a Thursday interview. That’s a bit tricky, however, because traditional TOU prices that peak in the afternoon might not help push customers to use more energy at times when the dreaded “duck curve” strikes the state’s grid.

The duck curve represents a day with cool temperatures, and thus less air conditioning use, but lots of solar power that reduces midday energy demand. Then, as the sun goes down and people start coming home from work, energy demand ramps steeply upward, putting pressure on grid operators and generators to ramp up production to meet it.

As CPUC’s proposed decision notes, “Impacts on the grid that need to be considered include not just peak usage periods, but also the deepening afternoon valleys resulting from increased deployment of solar, and the need for flexible ramping capacity. A default TOU rate must be flexible enough to address these changes while providing a degree of consistency for customers.”

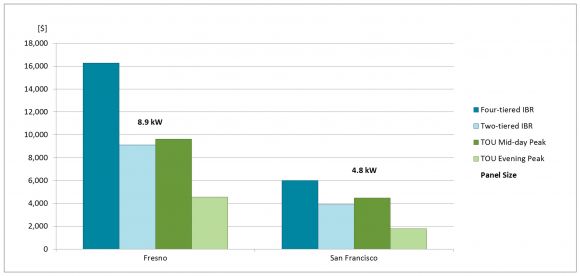

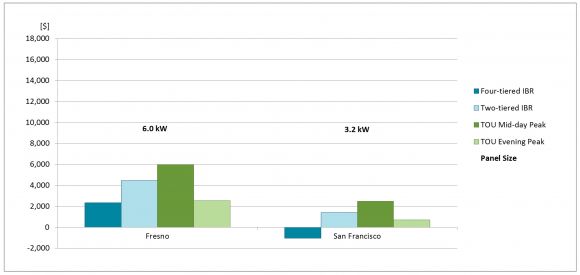

Creating TOU rates that can shift between mid-day peaks and evening peaks could help manage these changing grid conditions, and also increase the payback on customer-owned solar, according to an EDF analysis (PDF). The following charts show the net present value of a residential solar system under the current four-tier structure, the proposed two-tier structure, and using hypothetical TOU midday and evening price structures, first for high-energy-using households in sunny Fresno and foggy San Francisco, and then for average-load customers in both cities.

These charts back up the assertion that lower energy-using households could actually see solar become more attractive under a two-tier system, since the lower tiers will have to rise to make up for revenue lost from the removal of the highest tiers. But the real boost to solar’s value will come with the creation of TOU prices that provide incentives to generate and consume power when the grid needs it most.

“We simply need to update time-of-use, both the prices and the time windows, to align with the needs of the grid -- and then continue to improve our skills in communicating this to customers and our devices,” Fine said.

Minimum bills beat fixed charges for maintaining solar's value

The second big change that AB 327 opened up was to allow the state’s big three investor-owned utilities to charge flat fees of up to $10 per month to every customer, no matter how much power they consume. Utilities say they need that fixed fee to pay their fixed costs of maintaining the grid -- but solar advocates and ratepayer advocates say that they’ll penalize low-income customers and reduce the impetus to invest in solar and energy efficiency.

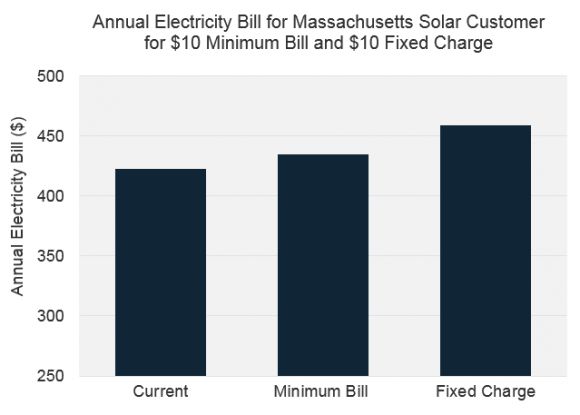

The CPUC’s proposed decision does allow for a monthly charge of up to $10, starting this summer -- but it does it in the form of a minimum bill, rather than as a fixed charge. That’s an important distinction, and one that GTM Research has determined will be much less harmful to net-metered solar’s economics, compared to the fixed charges being imposed on solar-equipped customers by utilities in Arizona.

The reason is fairly simple. A fixed monthly charge would add up to $10 to every bill, no matter what, while a minimum charge would simply fix the least amount of money a customer pays per month at $10. That means that net-metered solar household that spins its meter backwards to reduce their kilowatt-hour charge to $11, for example, would pay only $11 under a minimum monthly bill regime, compared to $21 under a fixed charge regime.

Here’s an analysis by GTM Research of the benefits of minimum bills vs. fixed charges in in Massachusetts, the first state to enact them.

“A minimum bill is generally preferable for solar and, for most solar customers, will have a minimal but non-zero impact on their bill savings,” Kann noted. TASC agreed, noting that “[m]inimum bills are more effective and fair than fixed charges. The excessive monthly fixed charges requested by the utilities are not justified and are contrary to the interests of customers who desire to invest in solar and energy efficiency.”

CPUC’s proposed decision does open the possibility for the state’s investor-owned utilities to request fixed charges in the future, striking a sour note for minimum-bill supporters. But it also requires the state’s big three utilities to “identify fixed costs for purposes of calculating a fixed charge” in future rate cases. That data could help inform another big CPUC proceeding, one asking utilities to determine how to incorporate the value of distributed energy resources like customer-owned solar into their distribution grid plans.