Natural-gas peaker plants may soon be under threat in a very real way.

“I can’t see a reason why we should ever build a gas peaker again in the U.S. after, say, 2025,” said Shayle Kann, a senior adviser to GTM Research and Wood Mackenzie, speaking at Greentech Media’s Energy Storage Summit. “If you think about how energy storage starts to take over the world, peaking is kind of your first big market.”

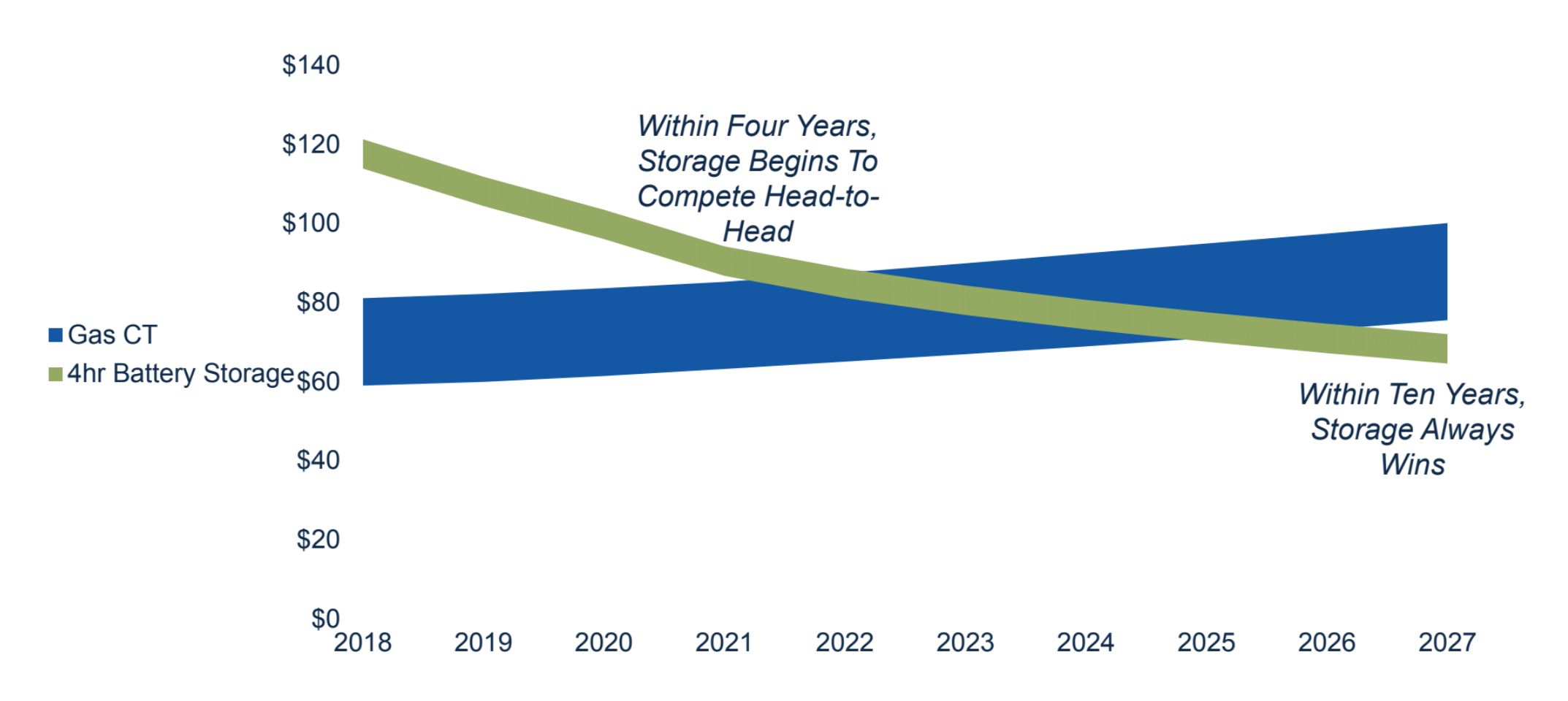

The data shows a very clear trend.

Today, lithium-ion batteries are competitive with natural-gas peaker plants in select cases. In a few years, competition will intensify across the country. And with costs only headed downward, Kann called overtaking peakers “a sweet spot” for battery dominance across the U.S.

Source: GTM Research/Wood Mackenzie

In four years, new natural-gas peakers will become increasingly rare. In 10 years, it's possible they'll stop getting built altogether.

“Peakers are expensive. Energy storage should be really good at displacing a peaker, and also you can use multiple values,” said Kann. “But not even incorporating the multiple values, energy storage is starting to get very close to the point where it can just beat a gas peaker, head-to-head, purely on an economic basis. A decade from now, energy storage always wins.”

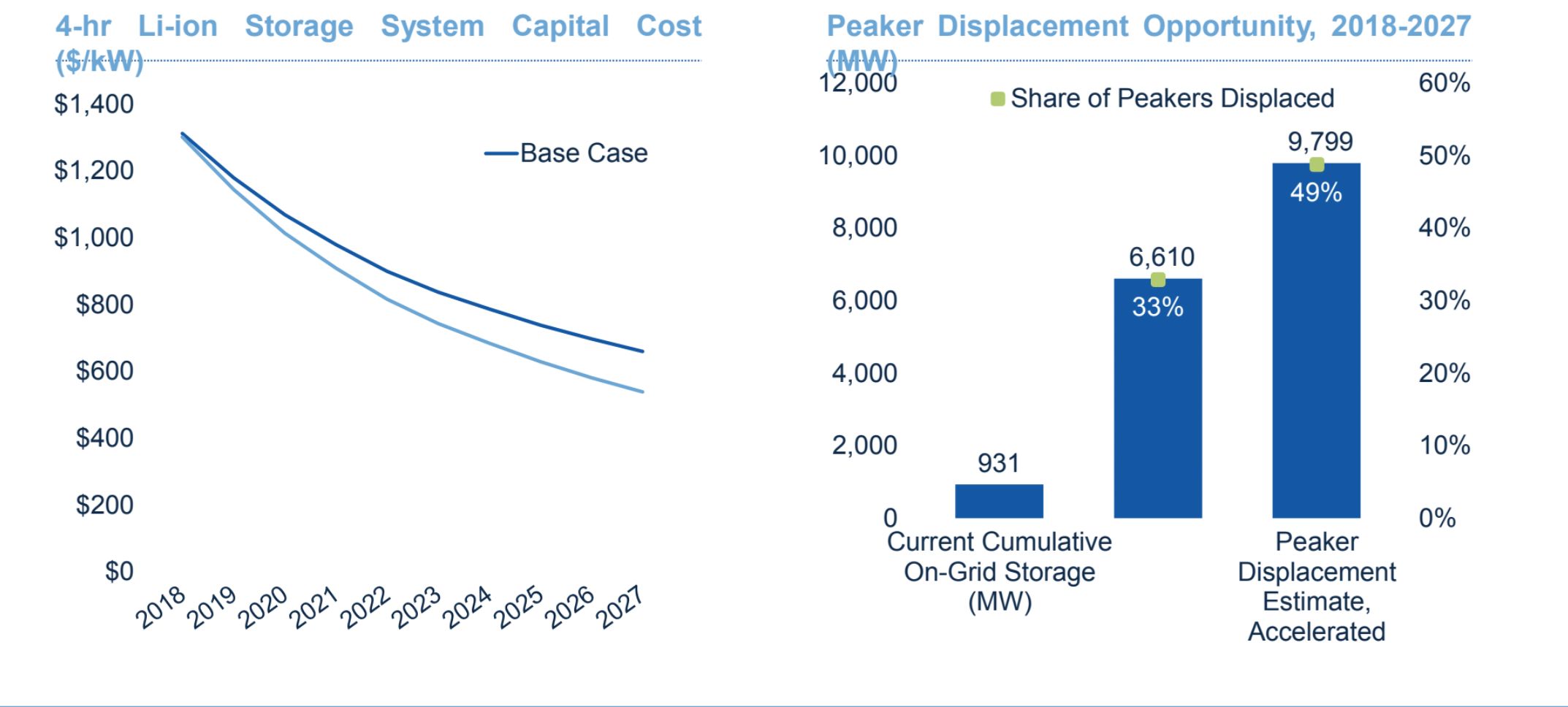

Over the next 10 years, the U.S. needs to add 20 gigawatts of peaking capacity to its grid. Over half of that capacity will come on-line in the latter part of the decade: 7,440 megawatts between 2018 to 2020 compared to 12,645 megawatts between 2023 and 2027. That gives energy storage more time to build an economic advantage.

If technology changes faster than expected, the economic argument for storage becomes more compelling.

GTM Research/Wood Mackenzie

While the U.S. market includes less than a gigawatt of storage today, it will replace a third of peakers under a base-case scenario in the next decade. If the market grows faster, storage may replace nearly half of those 20 gigawatts of peaking capacity.

“Time and time again in adjacent sectors like solar, and even in energy storage, technology costs have the capacity to fall faster than almost anybody expects,” said Kann. “Including us.”

These changes are catching regulators off guard. The most recent example: the California Energy Commission's decision to reconsider a gas peaking plant planned for Oxnard.

The California Independent System Operator found the peaker plant would be more expensive than storage -- in an analysis that used prices from 2014. After GTM pointed out the discrepancies between those costs and current industry pricing, NRG Energy, the plant’s developer, suspended its construction application.

That project isn’t completely dead, but the suspension leaves an opening for clean alternatives to meet the capacity need instead.

In South Australia, the need for grid stability and renewables integration prompted the installation of a 100-megawatt Tesla battery in record time. Tesla brought that battery on-line last month.

Gas peakers will still get developed in South Australia. But Tesla's battery could be a sign of things to come.

A report on the two projects from Wood Mackenzie and GTM Research found that batteries -- both alone or paired with renewables -- are not yet competitive with gas peaking plants in that region. But they’re on their way. In 2025, analysts project that standalone and renewable-hybrid batteries will beat out open-cycle gas turbine plants for meeting peak load.

Every year, said Kann, storage is closing in on that economic “sweet spot” that will allow it to beat out peakers.

Want to watch the rest of GTM's Storage Summit this week? Watch the livestream here.