Details on Tesla's new product line have slowly emerged since CEO Elon Musk sent out a cryptic tweet in late March. On a recent call with investors, Musk revealed that the company would introduce a consumer battery “for use in people’s houses or businesses fairly soon.” And, according to a note to investors, Tesla will launch “a very large utility-scale battery.”

There has been no shortage of hype around Tesla’s move into the standalone battery market, which the company will officially launch tonight. But Tesla is not alone in the space. The Silicon Valley company will have to compete with more established entities like LG Chem, AES Energy Storage and NEC/A123, as well as new entrants like Enphase, Sunverge Sonnenbatterie, and Stem, as well as many others.

If Tesla follows through with its plan to deliver utility-scale storage, it will also compete with Alevo, a Swiss battery startup that burst onto the scene last year with a mysterious lithium-ion chemistry and a $1 billion investment in a North Carolina manufacturing plant. But Jostein Eikeland, founder and CEO of Alevo, doesn’t seem too worried.

“One of the things Tesla has been fantastic at is to bring attention [to energy storage],” Eikeland said yesterday at Accenture’s International Utilities and Energy Conference in Chicago. “I take my hat off to them.”

Tesla is doing a good job showing how batteries can improve consumer choice and help the environment, similar to the way it has marketed its cars -- and it does make great cars, said Eikeland, who owns a Tesla Model S. But when it comes to batteries, Tesla’s technology and business model seem limited in scope, he said.

Many expect Tesla to focus its battery business on behind-the-meter projects for homes, offices and shopping centers. Greentech Media’s Eric Wesoff is betting that Tesla will unveil a 5-kilowatt home unit and a 200-kilowatt commercial-scale battery.

Alevo, meanwhile, is thinking bigger. Alevo makes shipping-container-sized lithium-ion batteries, called GridBanks, aimed at serving the utility market. The startup is expected to complete its largest battery installation this year, which will be 60 megawatts.

“We’re on the other [end of the] spectrum [from Tesla],” said Eikeland. “We don’t do Tinkertoys or things like that.”

“I don’t expect utilities to actually take those systems seriously"

The challenge for Tesla and other companies looking to deploy traditional lithium-ion batteries for utility applications is durability, said Eikeland.

Tesla has proven it can make industry-leading lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles, where power density and energy density are the most important attributes. But stationary batteries have different performance requirements; they need to be able to deliver massive amounts of energy and run deep cycles for several years.

Alevo’s sulfur-based inorganic lithium-ion electrolyte chemistry can respond quickly without overheating, and can charge and discharge repeatedly without degradation. In a recent test, Alevo's battery achieved 50,000 complete cycles without failure, according to Eikeland. And because the battery has an inorganic electrolyte, nothing in the battery reacts while it’s sitting idle. Alevo is so confident in its technology that it offers its clients a 20-year insured warranty.

In contrast, the conventional lithium-ion batteries that Tesla uses today generally have poor life spans, degrading with every charge. These batteries require rest periods between cycles to regain equilibrium, and are known to melt down and catch fire if overworked.

“To take that application and move it into the grid, where you have to give year-over-year performance guarantees -- you can’t play with those risks,” said Eikeland. “I don’t expect utilities to actually take those systems seriously in the long term, where you have to convince your ratepayers you’re going to be there for them every day, day and night.”

Eikeland isn’t just trying to disparage his competition. Bank of America’s John Lovallo expressed the same concern over Tesla’s ability to make high-performance stationary battery products -- and, ultimately, to make money, as the website Bidness Etc reports.

“I hope [Tesla] comes up with some really big breakthrough in batteries and really big breakthroughs in chemistry,” said Eikeland. “If not, I think it’s going to be a challenge [for the company] to go beyond solar smoothing.”

Putting value back into existing investments

To be sure, while the solar-plus-storage market is tiny today, it stands to become very lucrative in future. The Rocky Mountain Institute recently calculated that solar combined with storage could drastically reduce Northeastern utilities’ electricity sales, triggering $34.8 billion in lost revenues. Much of that loss could become earnings for companies like Tesla.

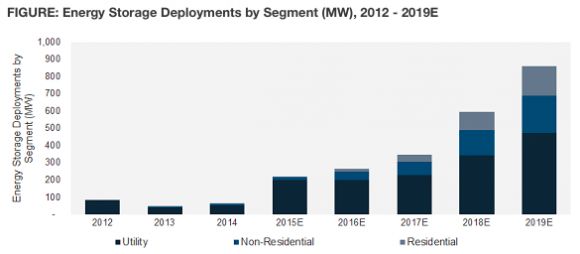

According to GTM Research, behind-the-meter batteries will make up 45 percent of the U.S. storage market by 2019, representing around 385 megawatts. Alevo is looking to tap into that market by working on behind-the-meter projects with industrial customers. But the company is mostly focusing on the other 55 percent, the utility-scale projects, which it sees as a near-term opportunity and the quickest route to reaching scale.

Large-scale batteries are like Swiss army knives, according to Eikeland -- they’re tools with multiple uses including frequency regulation, renewable energy integration, T&D deferral, spinning reserve, peak-shaving and time-shifting, ramping support and voltage support.

Accommodating increasing amounts of renewable energy is one driver for energy storage, but Alevo also sees a massive opportunity in reducing energy waste. It takes about 38 quadrillion British thermal units of fuel to power the United States’ electricity system, said Eikeland. Out of that, 18 quadrillion Btus are converted into electricity, but only 12 quadrillion Btus actually reach customers -- a 30 percent gap between the amount of electricity produced and the amount of electricity used.

These electrons “have no home,” said Eikeland. Alevo is trying to capture and use those electrons that are “so dearly and expensively produced.”

The savings are high. Alevo estimates it can increase efficiency at the average coal plant by 10 percent, while reducing greenhouse gases by 7 percent. Alevo recently submitted to the U.S. EPA that it can achieve $4 billion in annual savings per project split between stakeholders.

“We are probably the most unsexy company,” said Eikeland. Alevo isn’t offering some new whiz-bang consumer product; rather, "It’s about how do we capture and then reap the benefits out of the assets we have today.” The opportunity for utilities to make better use of their existing investments is particularly critical at a time when business models are changing and infrastructure is aging.

For a battery company, offering long-life products for megawatt-sized projects on the distribution system is the quickest way to reach a levelized cost where batteries can be deployed profitably, according to Eikeland.

In 2015, Alevo will deploy more than 200 megawatts' worth of battery storage in U.S. wholesale markets, in partnership with Customized Energy Solutions. If successful, Alevo would achieve in a single year what it took grid storage leader AES a decade to do. In 2016, Alevo will deploy more than 1 gigawatt worth of batteries in the U.S., said Eikeland, and will expand its business into Europe, China, Turkey and other markets

How Tesla plans to scale, “I don’t know,” he said.

Tesla has already started construction on the $5 billion Giga factory in Nevada, where it plans to produce 35 gigawatt-hours' worth of batteries by 2020. But as Bank of America’s Lovallo notes (putting aside any technical limitations of conventional lithium-ion batteries), it could take many years for Tesla to scale up this side of its business, while more established competitors move into the market.