This is a week that might, if we are lucky, live in green technology infamy.

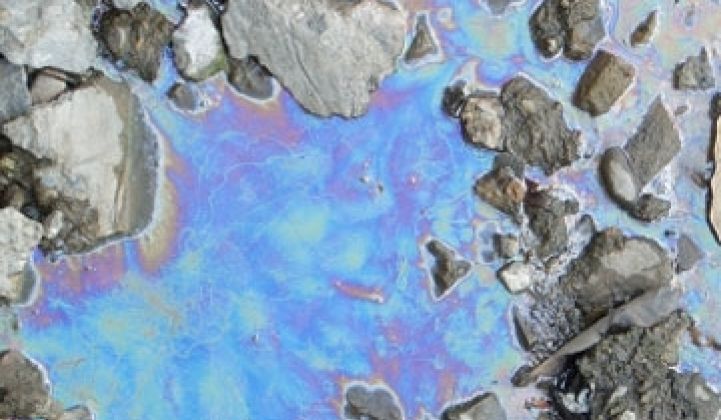

As you likely know, a massive oil spill off the coast of Louisiana threatens to become the largest environmental disaster in the U.S. in decades. Fishing and tourism in the region are already imperiled.

Meanwhile, a break in a water main in the Boston area has prompted officials to tell at least a million people not to use water from municipal systems and to boil any water they need to use for human consumption.

These are unqualified disasters by any measure and will harshly impact the people in those areas.

But, unfortunately, it is these kinds of disasters that Americans (and most people around the world) typically need to experience before they actually tackle a problem.

Almost 99 years ago, New York City and the rest of the nation were appalled by the deaths that arose from the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. The disaster led to regulations for workplace safety. Some historians also link it to the rise of the New Deal two decades later. Frances Perkins, who helped usher in many of the reforms, later became Secretary of Labor under Franklin Roosevelt. Al Smith also worked on the effort. He became governor of the state and paved the way for Roosevelt.

In 1969, the Cuyahoga River fire in Ohio and the oil spill off Santa Barbara prompted outrage among middle class Americans. The two incidents helped inspire the first Earth Day in 1970 which drew millions of protesters across the country. Then, in the 1970 elections, the Earth Day organizers helped unseat seven environmentally unfriendly Congressional Representatives, including the quite powerful George Fallon.

Soon after, President Nixon proposed the EPA. The measure passed 100-0 in the Senate and got through on a voice vote in congress. The Clear Air Act, the Endangered Species Act and other key pieces of legislation followed.

Experts have issued warnings about the fragile state of the U.S. water infrastructure for years.

"Roughly a third of the drinking water never makes it to the end user because of leakage to pipes. In older cities like Chicago -- where they have a 100-plus-year-old infrastructure -- 50 percent to 60 percent of the water leaks out of the pipes before it ever makes it through," General Electric's Jeff Fulgham told me in 2007.

The effort and money to fix the country's water problems, however, has been scant. VCs often admit that they want to, but generally don't, invest in water companies because the subsidized nature of the U.S. water market and the time required to solve infrastructure problems make it difficult for companies to make headway with their technology.

These two disasters will, potentially, now highlight the links between infrastructure, the environment and the economy. More importantly, they will create a flash point that will let people from different ends of the political spectrum unite behind a goal. Left or right, no one wants to see fishermen go broke.

These two incidents are also very tangible. Climate change and peak oil -- while real -- have been the subject of debate in part because the consequences will mostly occur in the future. In other words, the true impact remains invisible. It's a lot tougher to argue about the need to contain an oil spill. Even staunch fossil fuel advocates won't be chanting "Drill, baby, drill!" with quite as much gusto.

"My guess is that this won't become a big issue unless there is a thalidomide event," Richard Smalley, the now-deceased Nobel Prize winner told me a few years ago when asked if humanity would move away from oil gracefully. "We will have to see in the rear-view mirror that we are past the peak in worldwide oil production."

Luckily, the political system does often work well in disasters. Remember the rolling blackouts in California in 2000 and 2001? The state's current renewable energy policies grew out of it. By coincidence, David Brooks of The New York Times likened the growth of the green economy to the transcontinental railroad last week. It's an accurate metaphor, and far less divisive than the usual New Deal metaphor.

No one wanted this to happen and help needs to be rushed to these areas. But once the immediate problems are solved, hopefully we can then tackle the underlying issues.