Solar energy has grown “from a cottage industry to a mature industry in less than a decade,” said Schiller LLC Managing Director Mark Willingham. Schiller Automation, a 30-year-old, 260-employee manufacturing firm, based near Stuttgart, Germany, seized the opportunity early in solar’s focus on solar module and cell manufacturing.

The firm combined expertise in high-throughput manufacturing gained from the making of automotive and microelectronics assemblies and working with large thin substrates in the flat-panel displays to become the solar industry leader in the design and construction of thin film solar fabs (solar module factories) and automated process tools.

The thin-film module making process begins with glass and a thin-film solar panel maker’s unique cell design, Willingham said. Initially, Schiller worked primarily with amorphous silicon designs. As thin film makers using newer formulations like cadmium telluride (CdTe) and copper indium gallium diselenide (CIGS) entered the market, they sought Schiller’s expertise, which does not depend on any specific cell technology.

To date, Willingham said, Schiller has brought its deep experience to the automation of eleven complete fabs out of the “few of dozen in the world.” Nine are in full operation, one is ramping up and one is being delivered.

“Most are amorphous silicon,” Willingham said. “But we have also done CdTe and CIGS.” He could offer no more information without revealing proprietary information about the intensely competitive thin film industry. “In thin film, in particular,” he explained, “companies consider their own cell formula and method their secret to success and very private.”

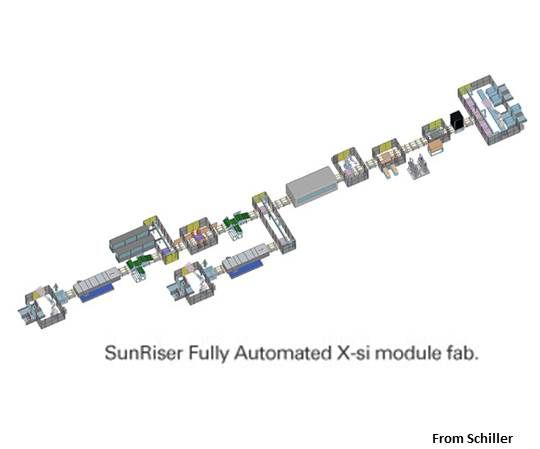

Schiller’s automation work has been either in automating specific steps in the cell- and module-making process or in developing and implementing a complete and unique process design. The company's expertise has also been called on, Willingham said, to cope with high failure points in the manufacturing process like junction boxes, back plates, rail attachments, and framing systems. In both these roles, Schiller has the capability to design and build tools and/or plan how they will fit into the manufacturing process.

“Most thin film companies,” Willingham said, “have a technology they think is the superior way to put that thin-film solar cell on glass.” To turn technology into modules, Schiller manages the flow of substrates through its customers’ process tools. “Some of those tools we might provide, some of those tools they will design themselves and some of those tools they will buy from other people for whom that is their only business. In the end, they have a solar module.”

Schiller plays a similar role in turnkey manufacturing systems, adding to each to fit unique needs. In some cases, Schiller also works on the design of the process “to connect the factory together.” The entire process must be precisely automated because of the chemistries involved. A delay between steps could interrupt and even harm or ruin the product.

A large fab can have up to 200 independent tools, each requiring monitoring and maintenance. Schiller oversees the flow of the process in the factory to minimize potentially devastating disruptions or unplanned downtime. Its unique Dynamic Buffering capability sustains fab efficiency, automatically and without the need for operator intervention, even through unforeseen or emergency interruptions.

“It gets to be pretty complicated,” Willingham said. “If you think of a thin film fab that’s going to make 120 to 150 megawatts a year, that’s upwards of a million substrates -- pieces of glass -- going through that factory. We provide all of the automation, the logic, the buffering, to manage all those substrates.”

Times are tumultuous in solar manufacturing. “There is much more supply of modules than there is demand right now,” Willingham said, but “the problem is more short-term. People have built way more modules and they’ve built way more capacity to build modules than is currently needed, [... so] 2012 will be a year in which there are too many modules for much if not all of the year.”

But business for Schiller’s BackBone and Pro-Load systems is good. “Mostly what we’re reading about is layoffs,” Willingham said. “We did not have any reduction in workforce in 2011 and none is anticipated. We’re busy as hell.” The company's strategy is simple. “We’re doing it,” Willingham explained, “by aligning ourselves with the companies we believe will be the market leaders of tomorrow.”

Based on the orders it is getting -- as well as those it is not getting -- Schiller has a unique vantagepoint on the current turmoil in the solar panel business and a strong sense of who the winners and losers are likely to be.

“We believe the type of company that will survive is either a large producer or a very diversified producer,” Willingham said. “We think customers are going to prefer to buy from producers who have a diversified portfolio. They make modules, maybe they make light bulbs, maybe they make many technology products, but they have a lot of different business elements that allow them to be a very stable company,” Willingham explained, “because people want to buy modules from a company they believe will be around 10 years from now when they might have a warranty claim.”

Schiller has, Willingham said, focused its efforts on the needs of those kinds of companies.

“Companies that did a good job, that make good products, that have a good model, are going to have a hard time surviving if this goes on for a long time because they are so focused in solar,” Willingham said. “Nobody will buy the routine, but there is a market for things that are innovative. Things that improve your efficiency. Things that actually save you money with your existing factory. Schiller makes these products and that is why we are growing while the market struggles.”