MEMC’s (NYSE: WFR) half-century in the semiconductor business made its 2009 acquisition of SunEdison seem an ideal match. It was -- at first, noted CEO Ahmad Chatila.

“Then the price of silicon collapsed,” Chatila said. “As 2011 wore on and supply exceeded demand significantly, MEMC struggled.” In response, he said, “we became aggressive in restructuring the company.”

Before moving from Cypress Semiconductor (NASDAQ: CY) to MEMC in 2009, Chatila said, he visited 150 solar and semiconductor companies worldwide. “I came to the conclusion that everybody would get crushed,” he said. “But I thought it would be 2014-15. I thought I had enough time to build capacity, do innovation and grow downstream. Unfortunately, I was wrong.”

In the solar business, Chatila said, “you have to have volume, price, and costs. When you own the customer, you own the price and you own the volume.” In a commodity business, Chatila added, “if you don’t have the lowest cost in the world, you don’t win. When I walked into the company, we had lost that race.”

But, Chatila said, “we had customers and long term agreements. We had to satisfy these instead of just building capacity.”

Though they could not avoid the crisis of 2011, Chatila said, “the team and I understood that the way you win is through technology innovation upstream and focusing on brand and customer relations downstream. When we get more pipeline and service customers downstream, we profit. And if we differentiate our technology upstream, we profit.”

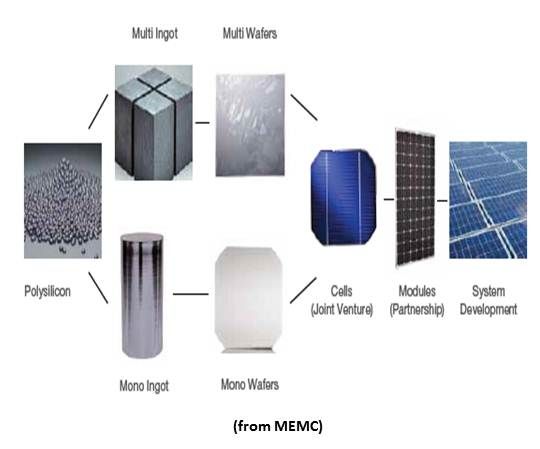

MEMC is a complex business, Chatila said. “The supply chain begins with polysilicon, then you make a crystal, a wafer, a cell, and then a module. Then you use other products to install and you sell the project, by financing it. And then you maintain the project. We make all the products. We don’t manufacture modules ourselves, but we have partnerships in making them. And we do development and operations and maintenance.”

The cheapest place to make polysilicon and crystals is the U.S., Chatila said, because factories are deployed in low-cost-electricity states. The cheapest place to manufacture modules and cells is China, because that part of the process is labor-intensive.

Most balance-of-system (BOS) products, except the inverter, he said, are made near the project, because transporting them adds to project costs. And the best inverter companies are German and American, Chatila said, because they have first-mover advantage.

Development, Chatila said, “is complicated. You have to be global. But decision making is always local. If you are tied to one country, one day you will wake up and there will be zero demand.”

The solar industry is trending toward midsize projects, Chatila explained, because “banks don’t like the high risk of projects above 100 megawatts and, because of that, you have to give them a lower price. And projects of less than one megawatt are not big enough to be interesting to banks and investors.”

Banks and investors, he said, “love 20- to 50-megawatt projects. They are under the radar, they are not very complicated and low risk. Banks don’t want to put a half-million dollars into a $3-million, one-megawatt deal. They want to spend a half-million dollars on a $100 million deal. And they don’t want to spend a half-million dollars on a $1 billion deal. That’s very high risk.”

MEMC recently moved its headquarters to Belmont, California, because, Chatila said, “we think California is the most interesting market in the world.” There is a business for residential and small commercial development, he said, “but you have to do it as a flow business.” California’s innovation in third-party ownership and other project finance models is facilitating such flows, while “in some places, third-party ownership is not as allowed as it should be.”

There are three elements in project finance, Chatila said. “During construction, you need money to build the project, before it is ready to be sold. When it is sold, there are two elements. One, the debt, you get from banks. The other, equity, you get from investors. We bring all that money together. That is one of the complexities of doing downstream.”

In MEMC’s Bulgaria project, he added, “The investors are from the U.S., Turkey and Saudi Arabia. The debt holders are OPIC, IFC and Italy’s Unicredit. On one project, 60 megawatts, a quarter-billion dollars, you have three investors and three debt holders, one from Italy, one international and one is U.S.”

MEMC is building around the world, Chatila said. Panel cost is “70 cents per watt, plus or minus.” The costs for building a project range “between less than $2 per watt to $3 per watt, depending on the country and the size of the project.”

From his experience in the semiconductor business, Chatila knew the Chinese would be able to make silicon modules cheaper than their competition. When they began taking market share, he said, other countries began imposing tariffs. “When you do that, you are saving 3,000 jobs. I do care about those jobs. But, since 80 percent to 90 percent of solar jobs are local, you are going to destroy 97,000 jobs, which I care about even more.”

And the tariff, he added, “is not impacting anything. When two countries go to war, guess who gains? The countries not at war. Guess where all the business is going -- to Korea, Malaysia, and Taiwan.”