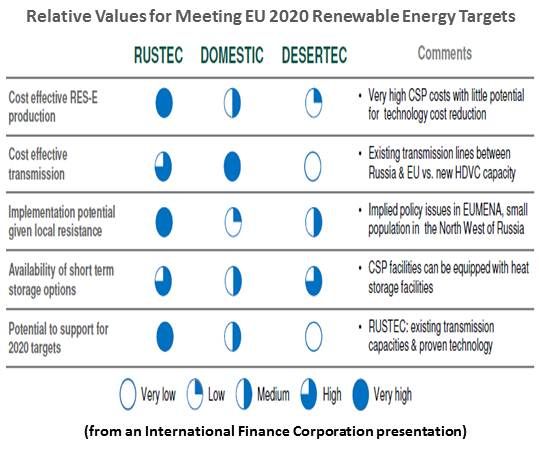

Renewables in northwest Russia could make a better investment than the multi-billion-dollar DESERTEC North Africa solar undertaking, according to researchers at the International Finance Corporation (IFC).

Backed by many of Europe’s biggest financial institutions, the DESERTEC proposal would invest an estimated 400 billion euros in solar power plants and wind projects across North Africa and in new, sub-Mediterranean HVDC transmission to the EU grid. Funded by a consortium of 56 shareholders in fifteen countries that includes multinational financial giants like Munich RE, Deutsche Bank (NYSE:DB), ABB (NYSE:ABB), E.ON, and HSH Nordbank, DESERTEC could meet as much as 15 percent of Europe’s 2050 electricity needs.

The IFC’s RUSTEC would capture northwest Russia’s wind, hydro and biomass resources, which, because they are abundant, concentrated and underutilized, could be more cost-effective to develop. Existing and new transmission and enhanced or new interconnections could deliver the renewables-generated electricity to the EU grid, according to a paper by the IFC’s Patrick Willems and Anatole Boute. IFC’s Russia Renewable Energy Project (RREP) has commissioned an independent study to develop cost, timeframe and capacity potential details.

The paper addresses the possibility of opposition from Russia’s oil and gas interests, but, it notes, RUSTEC could benefit the oil and gas industry because Russian natural gas resources will be needed as balancing reserves for the grid integration of renewables.

“IFC’s RREP is exploring the feasibility of the RUSTEC idea,” explains Boute. “EU and Russian stakeholders have confirmed a clear interest in the concept and recognize its potential benefits. Investors are also working on the idea.” But, he underscored, there have been no “clear commitments.”

“We do expect a slightly different group of stakeholders involving more private developers, along with governmental agencies,” Willems notes.

Developing resources outside the EU, the RUSTEC proposers acknowledge, would prevent EU member nations from reaping all the social and economic benefits of developing domestic resources. But it may eliminate barriers to new renewable capacity, such as affordability and NIMBY opposition.

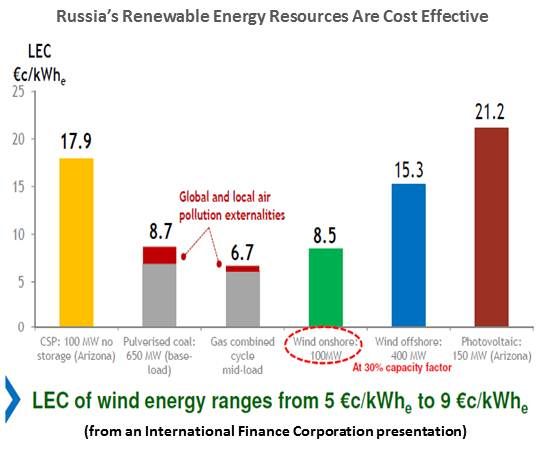

RUSTEC has two big advantages over DESERTEC, Willems and Boute say. Onshore wind’s LCOE is more cost-competitive than solar power plant technologies, as well as competitive with traditional grid generation sources in some places, and whatever new transmission and distribution infrastructure is needed to facilitate RUSTEC will be far more affordable than a new sub-Mediterranean transmission system.

Like DESERTEC, the RUSTEC driver would be the EU’s mandated 20 percent renewables by 2020 target and proposed 80 percent by 2050 goal. The EU directive establishing the 2020 target explicitly allows member states to draw on outside resources, the paper points out, if there is “a large renewable energy resource base that can easily be interconnected to the EU.”

“It is possible to implement projects before 2020 so as to enable EU Member States to meet their national targets at least cost,” Boute believes, if EU-Russia cross-border issues are resolved.

Russia’s electricity systems, the Boute-Willems paper said, “are interconnected with the network supervised by the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity.” There is transmission already in use between northwest Russia and Norway, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. New capability would be needed. Some plans are already in place.

“In the absence of interconnection reinforcement,” Boute believes, “renewable energy projects in Russia under joint projects are limited to existing Russia-EU electricity exchanges.”

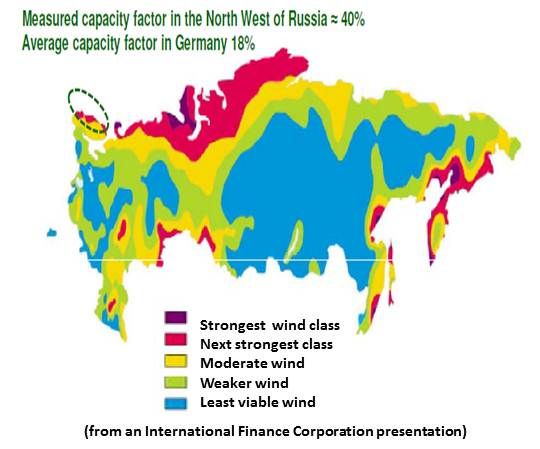

“The northwest of Russia is characterized by a particularly favorable and relatively cost-efficient renewable energy resource base,” the paper reports. “Onshore wind patterns are comparable to offshore conditions in the North Sea” with “an estimated 40 percent capacity factor.”

Forest biomass potential could be as much as 60 terawatt-hours. Hydropower can be significantly expanded and used as pumped storage. A recent report on hydro and wind power in northwestern Russia, Willems and Boute note, found a potential for 16.2 billion kilowatt-hours per year.

“The instability and unpredictability of the Russian investment climate negatively affects the business case,” Willems and Boute observe. But improved EU-Russian cooperation could result from RUSTEC if strengthened contractual, regulatory and political agreements reinforce power purchase agreements (PPAs) and bilateral investment treaties.

RUSTEC would need to balance EU economies’ loss of domestic opportunities with improved opportunities to export intellectual property and high-tech equipment. Russia must balance the consumption of its renewable resources with the development of its renewable industries and infrastructure.

Past disruptions to natural gas supplies from Russia to Europe may concern some EU member states. But, the paper notes, “There is thus no risk of interruption due to conflicts between Russia and transit countries, as was the case with the Ukraine–Russia gas interruptions.”

The building of pilot projects delivered through existing infrastructure is a feasible short-term “way forward,” Willems believes. “A pilot 200-megawatt wind project in the northwest of Russia is possible.”

For the longer term, the paper proposes an agreement between participating nations on ‘‘appropriate steps’’ toward further development and interconnection capability. It also suggests the possibility of using proceeds from the EU’s Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) to fund intermediate steps.

“The large renewable energy resource base in some parts of Russia, including the northwest, presents a cost benefit,” Willems and Boute believe. “Careful analysis will have to determine whether other costs such as network issues and risk premium could outweigh this benefit.”