Earlier this week, stealthy Swiss startup Alevo announced it’s investing $1 billion in a North Carolina factory that will eventually produce gigawatts' worth of a new kind of lithium-ion battery, one it claims can last much longer than current chemistries, and with no risk of overheating.

It’s a big claim from a company that’s shared almost nothing about its financing and technology until now. Technology breakthroughs in the advanced battery field are often announced with great fanfare. But often, the companies making these claims disappear without a trace -- or burn out after spending hundreds of millions of dollars of private investment or taxpayer funding.

Alevo hasn’t tapped any government grants or tax breaks so far, relying on private investments, equity funds and agreements with materials suppliers to reach its $1 billion target, CEO Jostein Eikeland said in an interview last week.

At the same time, the company that Alevo bought earlier this year -- and which appears to be the source of the startup’s mysterious, sulfur-based inorganic lithium-ion electrolyte chemistry -- had sought $112 million in state tax breaks to build a factory in Michigan, before it went under.

In May, Alevo Group acquired fortu PowerCell, a German company founded in 2007 that specialized in “rechargeable battery systems on the basis of inorganic components,” according to a Bloomberg profile. That sounds a lot like Alevo’s description of its sulfur-based, inorganic electrolyte, which Eikeland said has shown the ability to cycle up to 40,000 times in lab tests that began in 2011 without loss of power density, while operating at close to room temperature.

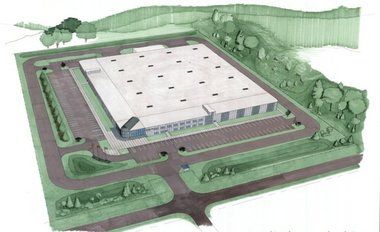

Alevo’s North Carolina factory is meant to package these cells into 2-megawatt, 1-megawatt-hour containerized “GridBank” units, at costs Eikeland said should be competitive with mainstream lithium-ion batteries at scale. It plans to produce about 200 megawatts of GridBank units for the U.S. market next year, and to reach multiple-gigawatt scale in the next few years, he said.

Fortu PowerCell, however, was unable to bring its own manufacturing plans to fruition -- even with significant government help. In 2010, fortu PowerCell was pledged $112.6 million in tax breaks by the Michigan Economic Growth Authority to build a battery factory in Muskegon Township. Fortu pledged at that time to invest $623 million and create about 700 jobs, and planned to start production in 2012.

But in January 2012, fortu pushed back the opening date to 2014, blaming poor economic conditions in Europe for the delay. The company's bankruptcy in September 2013 put an end to its plans for Michigan and canceled the state tax breaks. In that sense, fortu’s collapse is one of the least costly green technology missteps from Michigan, which provided tax breaks to factories built by companies like thin-film solar company Energy Conversion Devices and lithium-ion battery maker A123 Systems, which later went bankrupt.

It’s not clear what led to fortu’s insolvency, or whether it had anything to do with the efficacy of its chosen battery chemistry. Alevo Group hasn't commented specifically on fortu’s role in its new battery plans, or about any changes made to the battery chemistry, materials or design since it acquired them.

Eikeland has invested in high-tech manufacturing concerns such as magnesium die-casting in the past. In last week’s interview, he described his goal as redesigning these manufacturing operations to increase efficiency and lower cost, including utilizing the kinetic and temperature properties of the materials in use to improve the energy efficiency of various industrial processes.

This kind of expertise could lend itself to the advanced battery-making business, where manufacturing and process costs can play an important role in the cost of batteries coming off the line. The other big cost is materials -- and Alevo chose its sulfur-based chemistry in part because of its relative abundance and protection from wide swings in commodity costs, as compared to materials like lithium, which have far fewer sources, he said.

But Alevo will have to compete against giant lithium-ion battery manufacturers like Panasonic, Mitsubishi, LG Chem, Samsung, and Saft, as well as contenders like A123’s stationary battery business, now owned by Japan’s NEC. Tesla Motors, which is building a $5 billion Giga factory in Nevada to churn out both vehicle and grid-scale batteries using Panasonic's lithium-ion cells, is another obvious competitor. (Notably, Tesla is being offered $1.25 billion in tax breaks and incentives to build its plant outside Reno, more than twice what Tesla CEO Elon Musk was said to be asking from states seeking to host the Giga factory.)

To be sure, Alevo promises longer and deeper cycle life and low overheating risk. But its systems have yet to be tested at grid scale, unlike these competitors. Because its technology is new to the market, Alevo will also be competing against other startups with innovative technologies, whether they’re closed-system chemistries from Eos Energy Storage, Aquion Energy, Ambri or General Electric’s Durathon batteries, or flow batteries from Imergy (formerly Deeya), UniEnergy Technologies or ViZn Energy, to name a few.

Alevo also plans to become an integrated grid-scale energy storage provider, rather than selling its batteries directly. Eikeland said the company has built a software and data analytics platform that can provide better, cheaper and more effective storage solutions for government or private utilities, or serve to bid storage projects into energy markets on its own.

That could put Alevo into competition with the grid storage arms of energy giants like AES Energy Storage, NRG Energy and Duke Energy, big integrators like AES Energy Storage and S&C Electric, and providers of energy storage software such as Greensmith, Younicos-Xtreme Power, A123-NEC, 1Energy and GELI.