Three years ago, Wood Mackenzie reported on how water scarcity could impact global energy industries, from North American shale gas to Middle Eastern desalination.

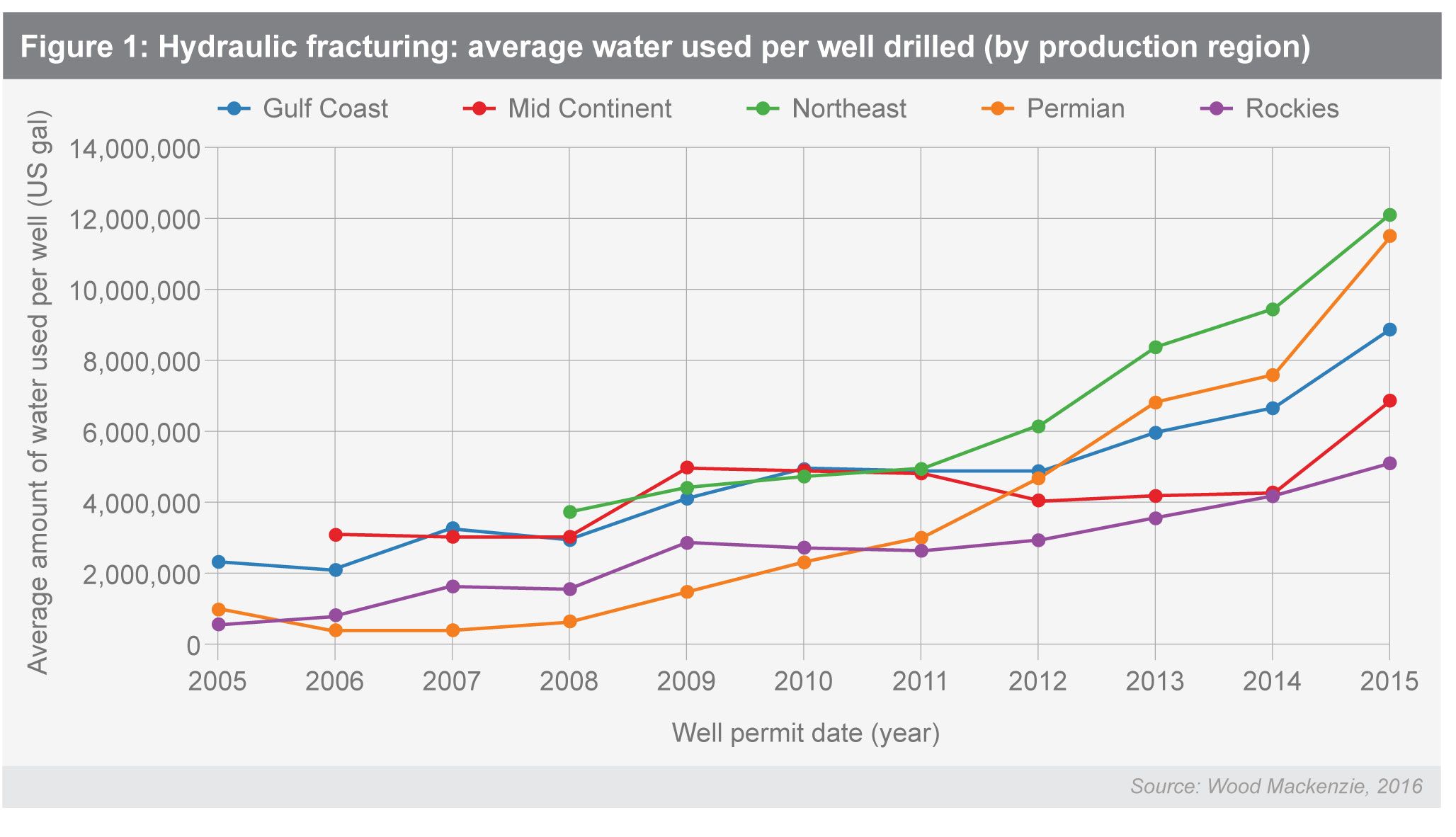

An updated report from Wood Mackenzie (which owns GTM) and Verisk Maplecroft finds the risks are greater in 2016, yet the market opportunity to address them remains largely untapped. In the U.S., for example, water costs for gas wells that use hydraulic fracturing doubled from 2012 to 2016, according to the latest report.

The increase is not necessarily because the cost of pumping water has increased, but because the amount of water used per well is increasing overall. Additionally, in Oklahoma, regulators have already asked gas companies to cut injection volumes at wells because of the risk of earthquakes, which increases costs because the spent water must then be trucked elsewhere. Some gas producers worry the restriction could be picked up by other states.

Eventually, however, the use of available water for fracking could reach a tipping point that would put even more pressure on gas companies. In some water-stressed areas in the U.S., fracking can use up to half of local water supplies, which often pits the energy industry against agriculture.

It's not just in the U.S. where the heavy reliance on fresh water for energy production in water-stressed regions seems out of whack. About 80 percent of China’s coal production lies in the north of the country, most of which lacks ample supplies of fresh water.

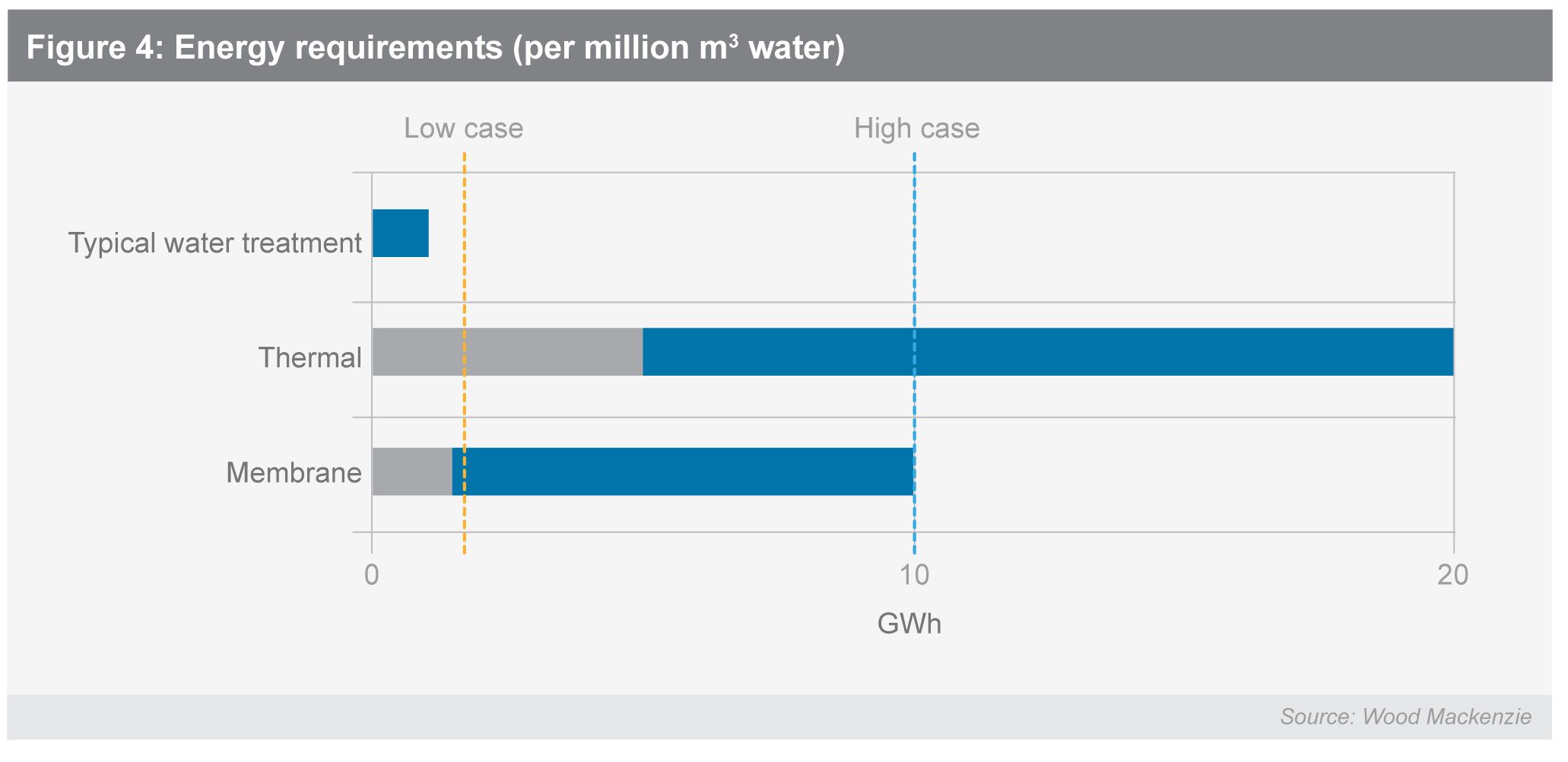

Another region that is grappling with the increased cost of water is the Middle East, which relies heavily on desalination, often powered by oil. Saudi Arabia, for instance, uses about 10 percent of its primary energy for desalination. That is becoming increasingly unsustainable as Saudi Arabia looks to diversify away from oil.

One solution is more efficient desalination technologies, which could be run on clean energy, likely solar, at least in part. The report found that connected solar powering reverse-osmosis desalination can be price-competitive with traditional desalination at oil prices between $20 to $30 a barrel.

While the global examples of how limited water availability is affecting energy production may seem disparate, they highlight the scale of the opportunity for novel technologies that could help increase the margins for the energy producers and governments that rely on this technology.

“The drivers are there,” said Will Nichols, senior analyst environment and climate change analyst with Verisk Maplecroft, who authored the follow-up to the original Wood Mackenzie report. “The risks of not getting into this are so great.”

Of course, one issue is cost. Water, while a rising cost in some regions, remains largely underpriced globally. In countries such as Saudi Arabia, subsidies further obscure the cost of water. Gulf nations are already investing in renewable energy and new desalination technology as they look to decrease subsides.

The first step will be more disclosure. On that front, the global energy industry is already a step behind, according to CDP (formerly Carbon Disclosure Project). It has the lowest level of water risk disclosure of any sector, yet the energy sector reports the second-highest level of exposure.

But providing disclosure soon will not be sufficient. It is not just a potential for a low-carbon future that energy companies must consider, but also a low-water one. “Simply considering water risks is unlikely to be a secure long term-position,” concludes Nichols. “The faster energy companies can position themselves to take advantage, the greater their rewards will be.”