Solar leasing gets so many headlines in the clean energy media, it seems like a foregone conclusion. But it’s not -- not yet, anyway.

About fourteen of 50 states currently offer a lease model for rooftop solar systems. One of the most active states is California, which offers plenty of lessons for other states, according to a new study by Climate Policy Initiative.

The study found that leasing has already outstripped buying rooftop solar by a significant margin. In 2007, about 10 percent of solar panels were leased by homeowners in California. By 2012, the proportion of leased solar soared to 75 percent. In the first quarter of this year, there were 71.3 megawatts of residential solar installed in California’s three investor-owned utility territories, according to GTM Research’s U.S. Solar Market Insight report.

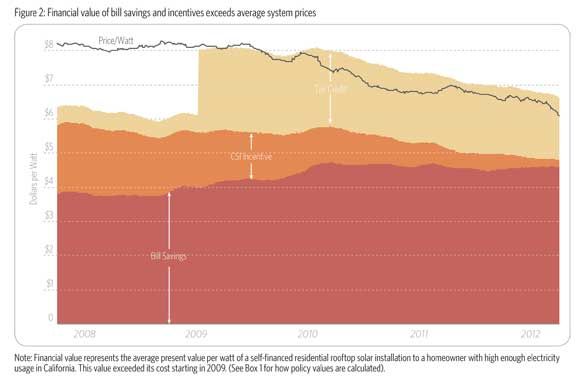

Much has changed in just a few years, and not just the falling cost of solar modules, said Uday Varadarajan, senior analyst at Climate Policy Initiative and co-author of the recent study. As leasing gained market share in California, the burden to federal taxpayers fell at the same time there was a declining state incentive through the California Solar Initiative (CSI).

“I think there are many ways that the solar lease experience shows the importance of renewables moving forward,” said Varadarajan.

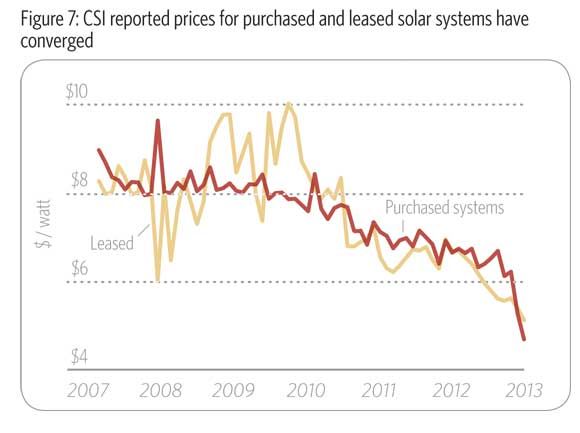

The study found that California’s incentives and the bill savings potential influence the reported price for solar leases, which correspond to the tax basis reported to the federal government. Although leases were at first more expensive than purchased systems for the federal government, that is no longer the case.

“State incentive programs and utility rates can affect costs for the federal government, especially for leased systems,” the study authors wrote. “Thus, the leasing model transforms an ostensibly cost-based incentive into one whose value depends on the amount of savings the project generates.”

As upfront incentives declined with the California Solar Initiative, leasing became increasingly attractive to Californians. The study authors estimate that the decline of the incentive from the CSI from 2008 to 2012 resulted in a 9 percent shift toward leasing rather than owning.

There are also other issues that other states could tackle to bring costs down further as they embrace solar leasing, argues Varadarajan, including interconnection issues, the split incentive of tenants and owners, and lack of clear information for consumer comparisons.

Even though the proliferation of solar leases is a win for clean energy, other states should also think about ways to engage the local utilities when building solar leasing programs. Duke Energy, for example, wants its subsidiary Duke Energy Renewables to be able to compete with solar developers, but it’s not allowed to under the current regulatory structure.

One lesson utilities can take from solar leasing companies is that service is paramount. “[Solar leasing companies] deliver on what [customers] are looking for,” said Varadarajan. “What they’re delivering is electricity as a service, but with lower cost and greater certainty over time.”