A solar installer in one Southern California city can take a set of plans to the proper authority and get a permit to build within 48 hours, a twelve-year solar industry veteran recently said. But in a virtually indistinguishable city of the same size that is immediately adjacent, Paramount Solar VP Todd Lindstrom said, “If I get it done in under three weeks, it’s a miracle.”

And, Lindstrom added, “I will be subjected to anything from silliness to lack of comprehension. That costs lots of money, to the point where you seriously consider charging extra.”

“Getting a permit is the choke-point in the process,” Clean Power Finance (CPF) CEO Nat Kreamer said, "[and it is] driving solar companies crazy today. It’s time-consuming, it’s costly and it makes for a bad end-consumer experience.”

Consumers want solar to be easy and quick, Kreamer explained. To do that, “we’re going to have to get the permitting barrier broken down. But we’re not going to get municipalities to change the rules. That’s where hope runs into reality.” The solution, he said, “is software.”

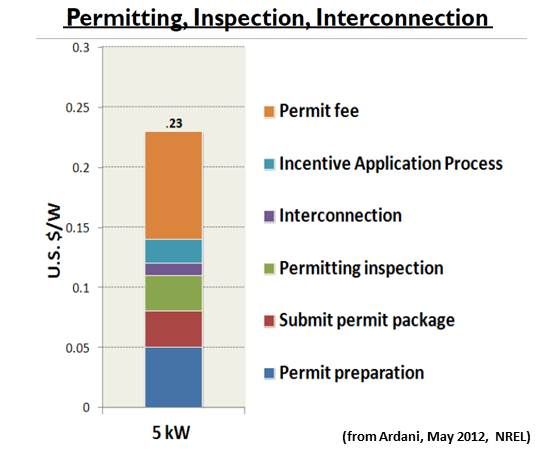

In its winning bid for a $3 million U.S. DOE grant to create an online database of local permitting standards, CPF estimated it could cut the balance-of-system (BOS) non-hardware (i.e., "soft") costs of installing a five-kilowatt (DC) residential rooftop solar system by more than $0.22 per watt. And there would also be other, less quantifiable, impacts, Kreamer said.

The U.S. Department of Energy's SunShot program opened a new $10 million competition last month in search of “innovative, sustainable, and verifiable business practices that reduce these soft costs to $1 per watt.”

“We have to solve this problem,” said Solar Freedom Now (SFN) Co-Founder Barry Cinnamon, a 30-plus-year solar veteran who has done everything from rooftop installs to running Westinghouse Solar (PINK: WEST). “The way we are going to solve it is on the national level because 18,000 cities, 3,000 utilities, 50 states, you’re never going to fix it everywhere."

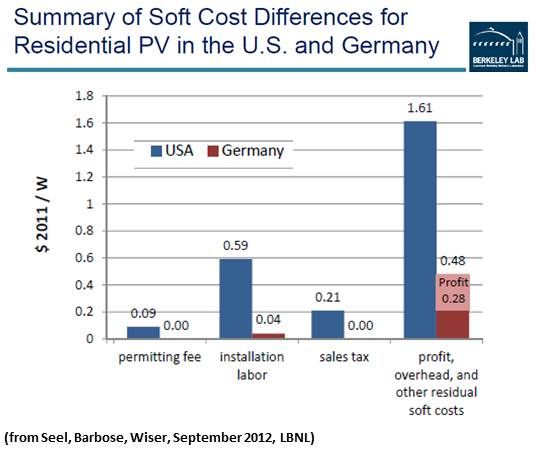

The difference in permitting is 21 cents per watt, he said. “But the difference in overhead is 95 cents per watt. There is a huge amount of other paperwork and requirements that aren’t permitting-related. A lot of those have to do with interconnection agreements, inspections required by the utility, incentive paperwork, fire codes, things that really aren’t specifically permitting.”

Rather than aggregating requirements, SFN proposes that “there are no requirements,” Cinnamon said. “If the system fits into a certain box, has certain characteristics, it requires no permitting. That’s what Germany did and it is working well.”

SFN is “working with stakeholders now to define those characteristics,” Cinnamon said, but “in broad-brush ideas, if the system was under five kilowatts, using solely UL-approved components, and installed by a licensed installer, you shouldn’t need any other requirements.”

The state of Vermont, Cinnamon noted, requires utilities to automatically interconnect standard rooftop solar systems within ten days after they are registered unless there is a major problem.

A national permitting database “can end up very complicated,” Cinnamon said, “and may not get us to where Germany is.” SFN “supports all efforts, including CPF’s,” he added. “They may learn what the common denominators for that five-kilowatt system are and that may be the template for a national policy.”

Cinnamon offered two examples. “Your standard gas hot water heater is dangerous,” he said. “But you can go buy one at Home Depot (NYSE: HD) and install it in a day.”

The other, he said, is a car. “You can go to a car lot and buy any car, even a 30-year-old rust bucket with flat tires that’s not safe at all.”

There is, Cinnamon said, “a quicksand of stupid regulations and requirements and we need a policy standard to bring to lawmakers in Washington, D.C., that has two million people who want it.”

“The real benefit from the National Permitting Database,” observed installer Next Step Living’s Brian Greenfield, “will come when the information gathered is used to encourage municipalities to streamline their permitting requirements.” Although unlikely, he noted, “one statewide or national set of requirements would be a giant step forward.”