Compromise legislation pertaining to solar policy in Massachusetts has been devised, and it could serve as a template for reforms in other battleground states.

Two important solar policies will change significantly if lawmakers approve the proposal.

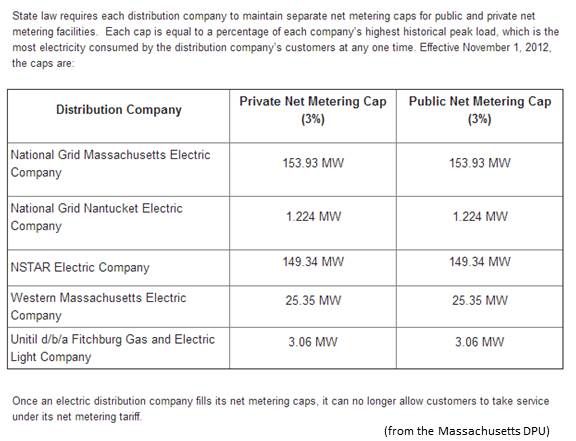

Net energy metering (NEM), which provides a retail-rate bill credit to solar owners for electricity their systems send to the grid, will remain in place unaltered, but the cap will be eliminated and ratepayers will have a “minimum bill” instead of the present “monthly charge.”

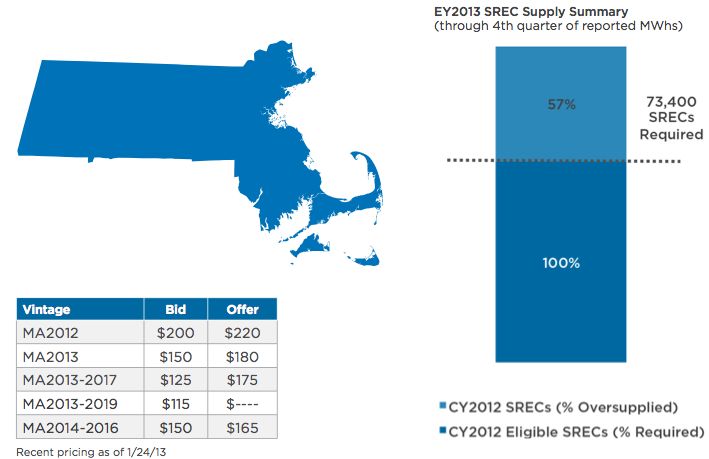

Solar renewable energy credits (SRECs), which create revenue for solar owners when purchased by utilities to meet state-mandated renewables obligations, will be replaced by a tiered, performance-based incentive system after a six-month period of transition during which both will be available.

The compromise was driven by politics and the marketplace, according to sources involved in the negotiations.

Under existing policies, uncertainty had begun to hamper solar installers. If a cap was to end NEM, the solar value proposition would be diminished. What's more, the state’s SREC market had become unreliably volatile. As Governor Deval Patrick's final term comes to an end, slowing solar growth threatens his legacy-enhancing target of a 1,600-megawatt installed solar capacity by 2020.

In March, key stakeholders were asked to find “a good long-term framework for solar growth” that would also make the governor’s target statutory, according to Carrie Hitt, SVP of State Affairs for the Solar Energy Industries Association.

Source: GTM Research SREC Market Monitor

A group of stakeholders including Northeast Utilities, National Grid, the New England Clean Energy Council, SEIA, and the Massachusetts Division of Energy Resources worked out the compromise, according to both Hitt and Janet Gail Besser, VP of Policy and Government Affairs for the New England Clean Energy Council.

“The biggest wins are that net metering will now be uncapped for solar and the introduction of performance-based incentives, offering predictable revenue streams paid out over fifteen years,” explained GTM Research Solar Analyst Cory Honeyman. The framework also revises the credit calculation downward for virtual-net-metered systems, which is expected to impact project economics for large ground-mount systems. “Key uncertainties lie in what the performance-based incentives will be set at and what the minimum bill will ultimately be.”

The key to the agreement was that each side got something it wanted, according to several participants in the 90 meetings that took place over three months of negotiation.

“We needed to see the cap on net metering eliminated or somehow adjusted,” Hitt said. “That’s what the solar industry was looking for. The Division of Energy Resources had always said it would revisit its SREC program. The minimum bill is an ask the distribution companies needed.”

Utility representatives “came to the table with open minds,” Hitt said. They were aware of solar’s popularity in Massachusetts but were also concerned about how to pay for the distribution system with increasing levels of distributed generation, increasing use of energy efficiency and demand response, and diminishing load growth.

Northeast Utilities and National Grid participants “didn’t come in with a lot of rhetoric,” Hitt said. “They didn’t come in saying, ‘Solar [is] costing us money.’”

There was no debate over solar’s costs and benefits, Hitt added, only a discussion about “cost recovery from all ratepayers for whatever the value of the distribution system is, in a way that doesn’t discriminate against any customers or discourage new technologies.”

The answer was the minimum bill approach, which, Hitt said, is not an additional cost or charge. “It just says that your bill will not go below a minimum amount.”

It is different than the fixed monthly fee that has been proposed or implemented in other states in response to concerns about infrastructure costs, Honeyman said. “The minimum bill sets a floor. And it only comes into play if a customer offsets enough of his or her monthly bill to fall below the minimum charge."

Some energy efficiency advocates say the minimum bill could discourage efficiency upgrades.

“There is a lot of confusion about the minimum bill,” the New England Clean Energy Council's Besser said. “I would be surprised if it has any impact on most customers’ bills. You do the energy efficiency and then you size your PV system appropriately to your usage. That’s how you save the most money.”

The agreement was, in fact, designed to get systems sized to fit customers’ loads, she said. “Net metering is supposed to be about sizing systems to your own use, not generating electricity to sell back into the grid and make money. That’s not why there is an incentive for solar.”

After the new policies are approved by the legislature, the minimum bill and the tiered performance-based incentive schedule will be established by the Massachusetts Department of Public Utilities in a standard regulatory proceeding.

The compromise agreement is “precedential,” according to Bryan Miller, Sunrun Public Policy VP and President of the Alliance for Solar Choice. "While high-pitched battles between utilities and the solar industry continue across the country, Massachusetts has found a collaborative path forward."

“This will save our ratepayers no less than half a billion dollars,” according to Ronald Gerwatowski, National Grid's SVP of Regulation and Pricing. “In a lot of states, you find solar developers at loggerheads and battling politically with utilities. We think solar is a very good technology, but we want to advance it at a reasonable cost to our customers. We achieved that here.”