2017 could be the year that fuel-cell technology finally breaks out. Here's why that may or may not happen.

First, the potentially good news.

Plug Power feels like an Amazon

Last week, fuel-cell builder Plug Power announced that Amazon, the world's largest online retailer, had gained the rights to buy up to 23 percent of the firm, in a deal that has Amazon spending $70 million in cash for fuel cells this year and $600 million over the course of the engagement. That's a big deal with the globe's pacesetter in the $20 billion materials-handling market.

Plug Power's system speeds up work in warehouses, replacing battery charging with proton exchange membrane (PEM) fuel cells and hydrogen systems designed to make forklift operation more efficient (although batteries are still used in the forklifts for surges). The Amazon deal is a multi-site agreement with fuel-cell forklifts being deployed at 11 warehouses.

While Bloom and FuelCell Energy's equipment runs on natural gas and requires a reformer, Plug Power's PEM fuels cells run on "five nines" hydrogen and work most productively with a hydrogen infrastructure at the customer site. (Note that industrial giant and JV partner Air Liquide is an investor in Plug Power.)

Amazon is in an efficiency arms race with Wal-Mart to dominate retail product fulfillment -- and fuel cells give the company an edge. Wal-Mart, already a Plug Power customer, has 250 forklifts at one location (thousands in all) -- and powering that fleet's batteries can account for up to 25 percent of the facility's electric bill.

The Bloom Energy fuel-cell wild card

Late last year, The Wall Street Journal reported that Bloom submitted a confidential registration for its IPO with the Securities and Exchange Commission. The report cited "people familiar with the matter." This action by Bloom falls under the Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act, which allows confidential filings for companies with less than $1 billion in revenue.

So, the only news was that Bloom had less than $1 billion in revenue last year. GTM has already reported that the structure of some 2015 notes suggested that we should be hearing more about Bloom's IPO right about now.

The energy company has raised more than $1.2 billion since 2001, from investors including the New Zealand Superannuation Fund, KPCB, NEA, Goldman Sachs, DAG, GSV Capital, Apex Venture Partners, Mobius Venture Capital, Madrone Capital and SunBridge Partners.

Board members include John Doerr of KP and former U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell.

Bloom builds fuel cells of the solid-oxide variety with natural gas as the fuel. There is no heat resource in the Bloom Box as in other CHP fuel cells. The 200-kilowatt units are intended for commercial and industrial applications, and the firm boasts an all-star list of customers, including Adobe, FedEx, Staples, Google, Coca-Cola and Wal-Mart.

Bloom's most recent $2.9 billion VC valuation dwarfs the collective market cap of the public fuel-cell firms, and its revenue might be greater than the collective revenue of those other firms.

The 15-year-old startup claims to have installed more than 200 megawatts of its Bloom boxes in the U.S. We'll look for the details in the company's highly anticipated S-1.

And now for the not-so-good news

In keeping with GTM tradition, here's a just-updated list of the top three profitable publicly held fuel-cell firms:

1.

2.

3.

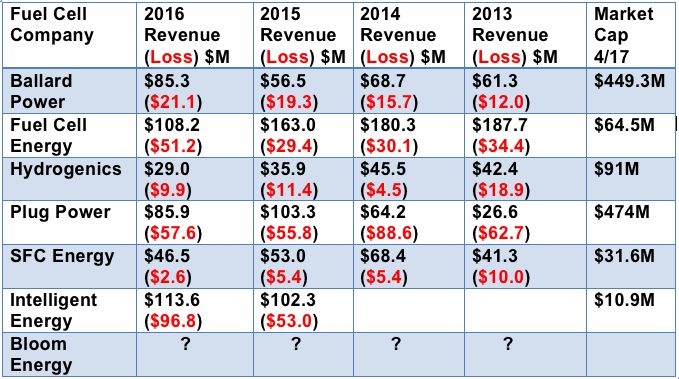

The table below gives a breakdown.

FIGURE: Revenue and Losses at Publicly Traded Fuel-Cell Companies

Source: Company reports

Fuel cell themes: Imminent profits remain imminent

Fuel cells employ an assortment of membranes, catalysts and temperatures, but in almost all cases, the membranes are difficult and expensive to fabricate, the catalysts are rare and expensive (typically platinum or palladium), and the temperatures required in the processes are relatively high. Fuels range from natural gas to methanol to butane to hydrogen. There are ongoing efforts to reduce the need for expensive metals and to improve the reliability and lifetime of the fuel-cell stack.

Leading technologies include proton exchange membrane (PEM), solid oxide (SOFC) and molten carbonate (MCFC). There are a number of other technologies, all equally adept at oxidizing investor capital. GM, Hyundai, Honda, Johnson Matthey, Panasonic, Siemens, Samsung, Sharp, Toshiba and Toyota have all invested in fuel-cell technology.

FuelCell Energy CEO Chip Bottone told GTM in a previous interview that his firm will be profitable when it achieves an 80-megawatt-per-year run rate. Late last year, Fuel Cell Energy laid off 96 positions or approximately 17 percent of its global workforce. Plug Power CEO Andrew Marsh told GTM that his firm would be profitable in 2013. Last week, he suggested that could occur in 2018. Bloom Energy was rumored to be close to profitability in 2013.

A profitable year for a publicly traded fuel-cell company would break a 100-year drought in the sector.

Fuel-cell vehicles, the DOE and fuel-cell startups

Globally, more than 60,000 fuel cells, totaling over 300 megawatts, were shipped worldwide in 2015. That's up from 50,000 fuel cells shipped in 2014, a total of 180 megawatts, according to a DOE report (PDF). The fuel-cell industry grew to $2.2 billion in 2014, up from $1.3 billion in 2013, according to the DOE report.

Hydrogen fuel-cell cars are not selling very well, due in large part to lack of fueling infrastructure and limited product offerings. But, just as battery-powered buses might drive the next spurt in lithium-ion EV drivetrain growth, so might buses drive the fuel-cell industry. In 2015, there were more than 370 fuel-cell systems delivered or on order for fuel-cell bus deployments, according to the DOE.

VC funding for fuel cells has been negligible, and the future availability of DOE funding for fuel-cell programs is now uncertain amid budget talks. But innovation continues nevertheless. A new firm, Watt Fuel Cell Corp., a developer of a solid-oxide fuel cell that runs on propane, natural gas and diesel, is using an automated printing process to perform some of the manufacturing steps.

Fuel-cell market forecasts are all over the map, however. The research firm MarketsandMarkets sees a $5.2 billion industry by 2019, with a compound annual growth rate of 14.7 percent from 2014 to 2019. According to a 2014 report from Navigant Research, the global revenue for stationary fuel cells will grow from $1.4 billion in 2013 to $40 billion in 2022, while WinterGreen Research sees the stationary fuel-cell market poised to increase to $14.3 billion in 2020.

In the face of these wild projections, a 2013 study by Lux Research found that in spite of the billions spent on R&D by government and industry, “The dream of a hydrogen economy envisioned for decades by politicians, economists, and environmentalists is no nearer, with hydrogen fuel cells turning a modest $3 billion market of about 5.9 gigawatts in 2030.”

Forget the forecasts. Keep your eye on the execution of that Plug Power/Amazon deal, and watch how Bloom fares as it attempts to go public. That will be a better indication of the health of the fuel-cell industry and the state of the race toward profitability.